The interwoven story of a dog, the University and various peopleHachiko and UTokyo

Of all the dogs that have some kind of association with the University of Tokyo, Hachiko has to be the most famous. Statues of the loyal dog have been erected in Tokyo’s Shibuya City as well as in the city of Odate in Akita Prefecture and in the Hisai area of Mie Prefecture. He has also been immortalized in film, with movies telling the story of his life made in Japan, the United States and China. Hachiko has thus been internationally renowned; however, the same could not be said for his owner. Hachiko was born in 1923 and died in 1935. This year (2023) thus marks the 100th anniversary of his birth. In the following, we share new stories about Hachiko and UTokyo that we have heard from related parties — stories that began on the 80th anniversary of the dog’s passing.

- In celebration of the 100th anniversary of Hachiko’s birth

- https://hachi100.visitakita.com/top/en/top/

1.

The mastermind behind the statue reflects on Todai Hachiko Monogatari

Emeritus Professor, The University of Tokyo

Professor, Faculty of Well-being, Musashino University

A story that begins with a philosopher’s love for the University

Upon entering the University of Tokyo’s Yayoi Campus from the No-seimon Gate, you will soon see the statue of Professor Hidesaburo Ueno and his dog, Hachiko, to your left. Unveiled in 2015, the statue quickly became a new campus landmark. The story behind the statue originates with philosopher Masaki Ichinose, who was then a professor at the Faculty of Letters.

“Hachiko is famous both in and outside Japan thanks to the movies that have been made about him,” says Professor Ichinose. “But the fact that his owner was a professor at UTokyo was not well known, even among faculty. I thought it was silly that the dog was famous for waiting for his owner, but the owner himself was not widely known.”

Having been a dog lover since he was a boy, Professor Ichinose could not stop crying while watching the movie Hachiko Monogatari (The Story of Hachiko). It was perhaps not unexpected, then, that he would be the one to come up with the idea of erecting a statue commemorating Hachiko on the 80th (hachi-ju in Japanese) anniversary of the beloved dog’s passing. Having visited universities in the United Kingdom for his research, Professor Ichinose couldn’t help but notice that tourists at the Alice in Wonderland shop would also cross the road to see where Charles Dodgson (famously known as Lewis Carroll) had taught at the University of Oxford. The University of Cambridge, meanwhile, is well known as the alma mater of both A.A. Milne, author of Winnie-The-Pooh, and his son, Christopher Robin.

“As a UTokyo faculty member, I thought our university should also have a unique story,” recalls the professor. “If the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge can have the stories of Alice and Pooh, why can’t UTokyo have the story of Hachiko? Out of love for the University, I guess, I wanted to use the story as a way to draw some attention to UTokyo.”

Initially planned for a different site

In the autumn of 2010, Professor Ichinose shared his idea with Shinichi Sato, who had been a professor at the Faculty of Letters and was then a vice president of the University. The professor also consulted Professor Haruhiko Masaki, a fellow committee member who was then teaching at the Faculty of Agriculture, where Professor Ueno had worked. He was also able to quickly obtain the approval of Professor Sho Shiozawa, then the head of the laboratory that considered Professor Ueno to be its founding father. Gaining the support of these key people gave the project momentum, and a group of 14 members (“Group for erecting a statue of Hachiko and Professor Hidesaburo Ueno at UTokyo”) was soon formed. After much consideration, the Group finally decided on a statue depicting the gleeful reunion of a young Hachiko and his master. Tsutomu Ueda, a sculptor whom Professor Shiozawa had met at the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition, was asked to create it.

“First, we visited an Akita dog breeder to take photos of dogs jumping up on Professor Shiozawa to use as samples,” explains Professor Ichinose. “We then took these to the sculptor’s studio in Nagoya (Aichi Prefecture) to explain the details of our request. Mr. Ueda made a prototype of the statue using his wife as a model for its face, which perhaps is why in the final statue Professor Ueno has a somewhat gentle expression.”

Monetary issues were soon resolved, with the statue being funded by donations made via the UTokyo Foundation. Where to put the statue was not so easily decided, however, with some proposing that it be erected at the Komaba Campus. In the end, the Group settled on the Yayoi Campus, where the Faculty of Agriculture is located and where Hachiko’s internal organs are still kept. A site on the main road extending from the No-seimon Gate was initially proposed as the location for the statue. This location was thought to be a straightforward place to put this kind of symbolic landmark, but after it was pointed out that the spot bore little relation to the research conducted by Professor Ueno and his successors, the site was changed to its present position.

Unveiling ceremony attended by an elderly woman who had actually petted Hachiko

-

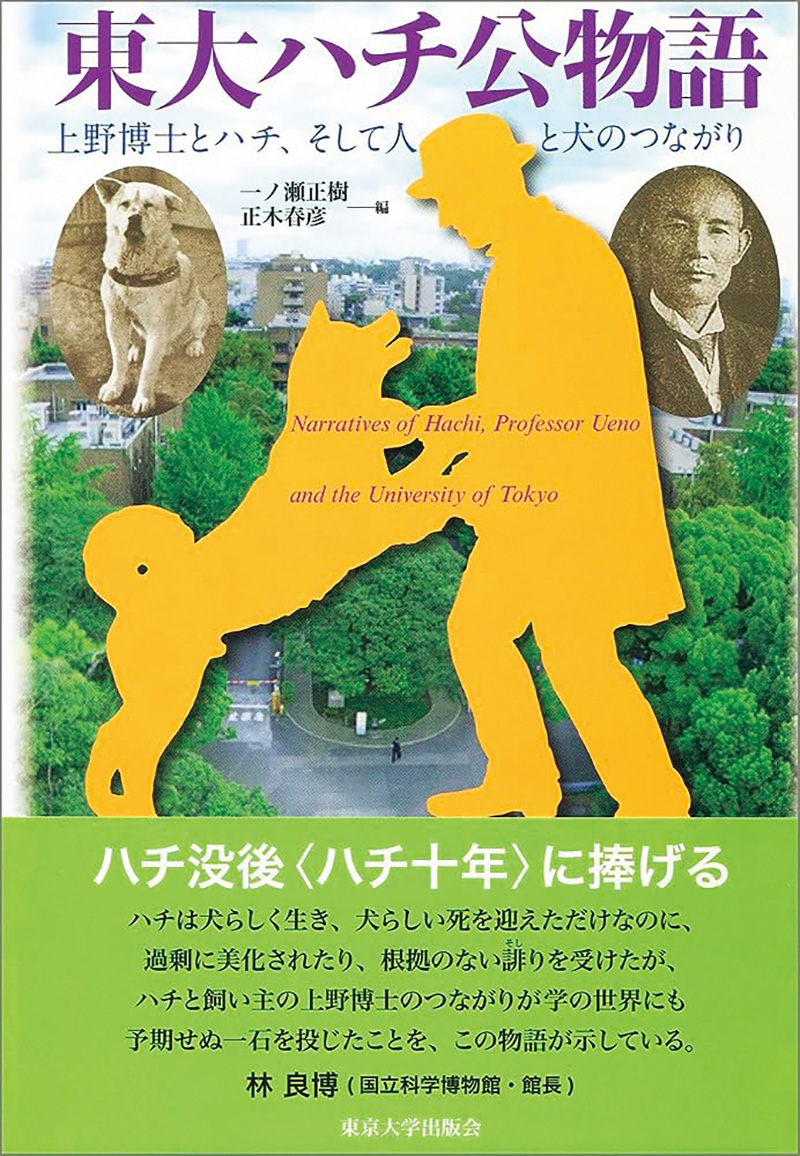

Todai Hachiko Monogatari (“The UTokyo Hachiko Story”) (Edited by Masaki Ichinose and Haruhiko Masaki, University of Tokyo Press, 2015)

This new Hachiko story was informed by a range of disciplines, including philosophy, zoology, dead body science, sociology and land environmental engineering. “There were some critics of the plan to use the dog’s popularity to draw attention to the University, perhaps because there is this notion that universities should be solemn and dignified places,” says Professor Ichinose. “However, if you read the prologue, you will soon see that the book actually embodies academic values.”

To gain support for the project, the Group held a symposium in 2014 titled “Todai Hachiko Monogatari” (“The UTokyo Hachiko Story”) and also started work on a book to be published under the same title. The idea of “studying how people think about dogs,” which was generated in the process, led Professor Ichinose to explore new philosophical ideas.

Finally, on March 8, 2015, an unveiling ceremony for the statue was held. Among the many attendees were an Akita dog that bore a strong resemblance to the original Hachiko and an elderly woman who had actually met and petted Hachiko when she was a child. The event got a lot of media coverage and was well received.

“Some people even left coin offerings at the statue, perhaps wishing that they could reunite with a loved one,” remarks Professor Ichinose.

A pet cemetery in Lafayette, New Jersey (USA) contacted the University with a proposal to make a replica of the statue. After giving the idea considerable thought, the Group decided to provide the mold of the statue on loan. Subsequently, in October 2016, an unveiling ceremony for the replica was held on-site at the cemetery.

Having left UTokyo in 2018, Professor Ichinose no longer gets to watch over the statue on a daily basis. He still feels great affection for it, however, and expresses concern that the delicate areas around the briefcase and collar might break. Meanwhile, the professor has returned to studying the Cynics of Ancient Greece, who endeavored to live “like dogs” (the Greek word kynikos means “dog-like”), and is offering new insights about their ideas.

2.

Interview with the Laboratory’s 10th professor about Professor Ueno’s agricultural civil engineering method

Shuichiro Yoshida

Professor, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences

Professor Ueno’s vision ahead of its time

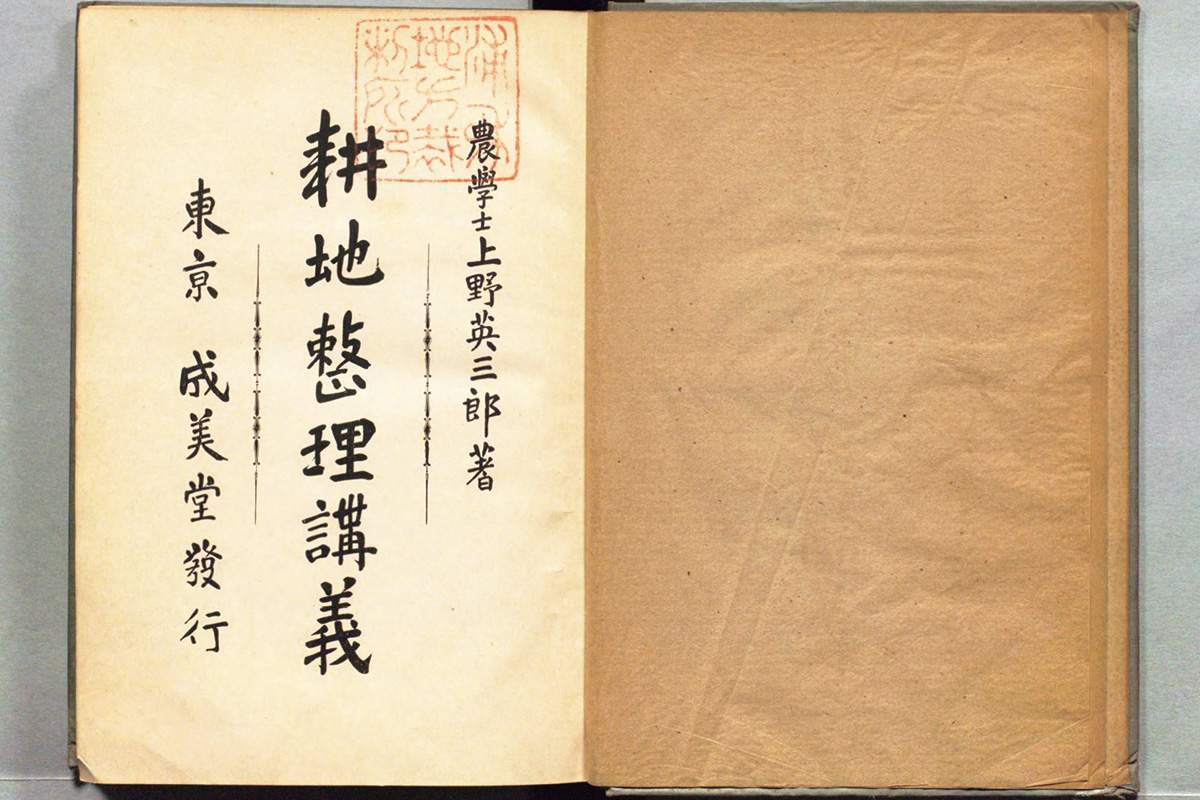

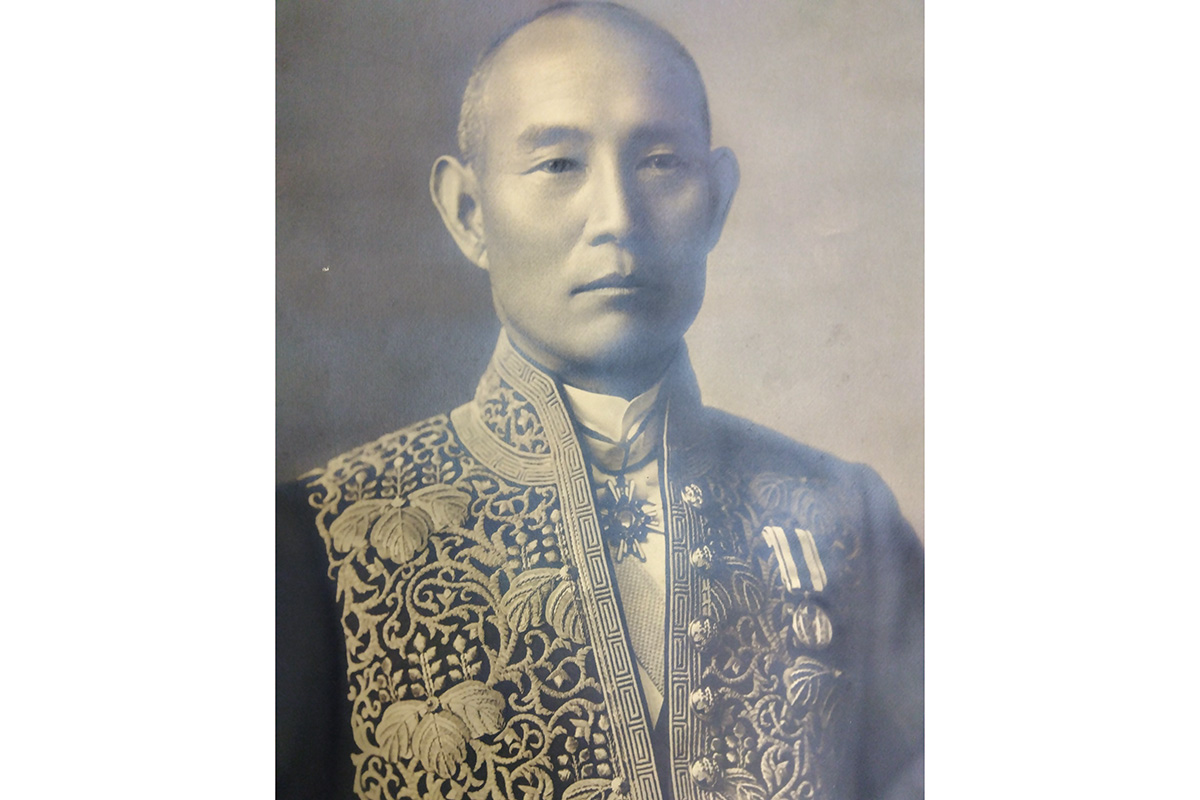

Professor Hidesaburo Ueno, the owner of Hachiko, is known for his work in establishing agricultural civil engineering studies in Japan. Agricultural civil engineering is a technical field concerned with developing agricultural land and improving the local environment based on irrigation and drainage. After working as an engineer at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, he studied in Western countries to acquire knowledge about advanced theories of arable land reform. Upon his return to Japan, he taught at the School of Agriculture (predecessor of UTokyo’s Faculty of Agriculture) and wrote a book on arable land reform based on his lectures titled Kochi Seiri Kogi (“Lectures on Land Reform”).

One of the theories described in his book concerns the plotting of paddy fields. At that time, not all plots were adjacent to waterways and agricultural roads, making cultivation inefficient. For the plots that were adjacent to waterways, in some cases there was no separation between irrigation and drainage. To address these issues, rectification methods such as denku kaisei (paddy revisions) and keihan seiri (causeway adjustments) were promoted, but the ways in which these methods were enacted varied by region, with many employing unsuitable designs and construction work. Professor Ueno criticized this state of affairs, proposing a new theory that took an integrated approach encompassing the characteristics, structures and layouts of plots, roads and waterways.

“Professor Ueno’s theory was not immediately accepted, however,” observes Professor Shuichiro Yoshida. “He had a far-seeing vision, which seems to have been too advanced for farmers of the time to implement.” Professor Yoshida is the 10th professor of the Laboratory of Land Environmental Engineering, which originated out of the agricultural engineering seminar inaugurated by Professor Ueno.

In order to carry out the land reforms as Professor Ueno proposed, plots would have had to be made bigger through consolidation, and machinery would have had to be introduced for greater efficiency. At that time, however, landowners were able to increase their yields simply by forcing their tenant farmers to work longer hours, so they were not keen to make investments in real reform.

“Following the postwar agricultural land reform, individual farms had more incentives to implement Professor Ueno’s theories in order to boost the productivity of their land, making the ‘Ueno method’ the standard for paddy farming in Japan,” explains Professor Yoshida.

Great achievements also made as an educator

Professor Ueno communicated his ideas at seminars and through his books, and those who learned from him later spread his ideas throughout Japan, which led to the development of both researchers and engineers in the field. Japan’s first scholar in agricultural civil engineering thus also made great contributions as an educator. The magnitude of respect paid to Professor Ueno is evident in the fact that after his death, his students built a tomb for him as well as a monument to Hachiko.

“Professor Ueno’s partner, Yaeko, was his common-law wife and this meant they were buried at different gravesites,” explains Professor Yoshida. “However, as a result of efforts made by his successors, Yaeko has been resting together with Professor Ueno and Hachiko in Aoyama Cemetery since 2016. One of those successors is Professor Sho Shiozawa, who was the Laboratory’s ninth professor.”

Agricultural civil engineering studies, which Professor Ueno initiated, gradually expanded its scope of research over time to include the natural environment and ecosystems. The academic society for the field, the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Reclamation Engineering, which was established in 1929, changed its name to the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage and Rural Engineering in 2007. According to Professor Yoshida, a recent challenge in this expanded field has been flood control in river basins.

“We cannot deal with flood damage caused by climate change simply by improving the river environments,” he says. “We need to take the broad approach of implementing measures to use the entire basin, including farmland, to mitigate flood damage. Farmland also has the ability to slow down the outflow of flood waters. As successors of the Ueno method, we regard it as our responsibility to pursue the use of farmland for flood control, while minimizing the effect of such use on crops.”

Read part 2 here

Hachiko and UTokyo (part 2)