Title

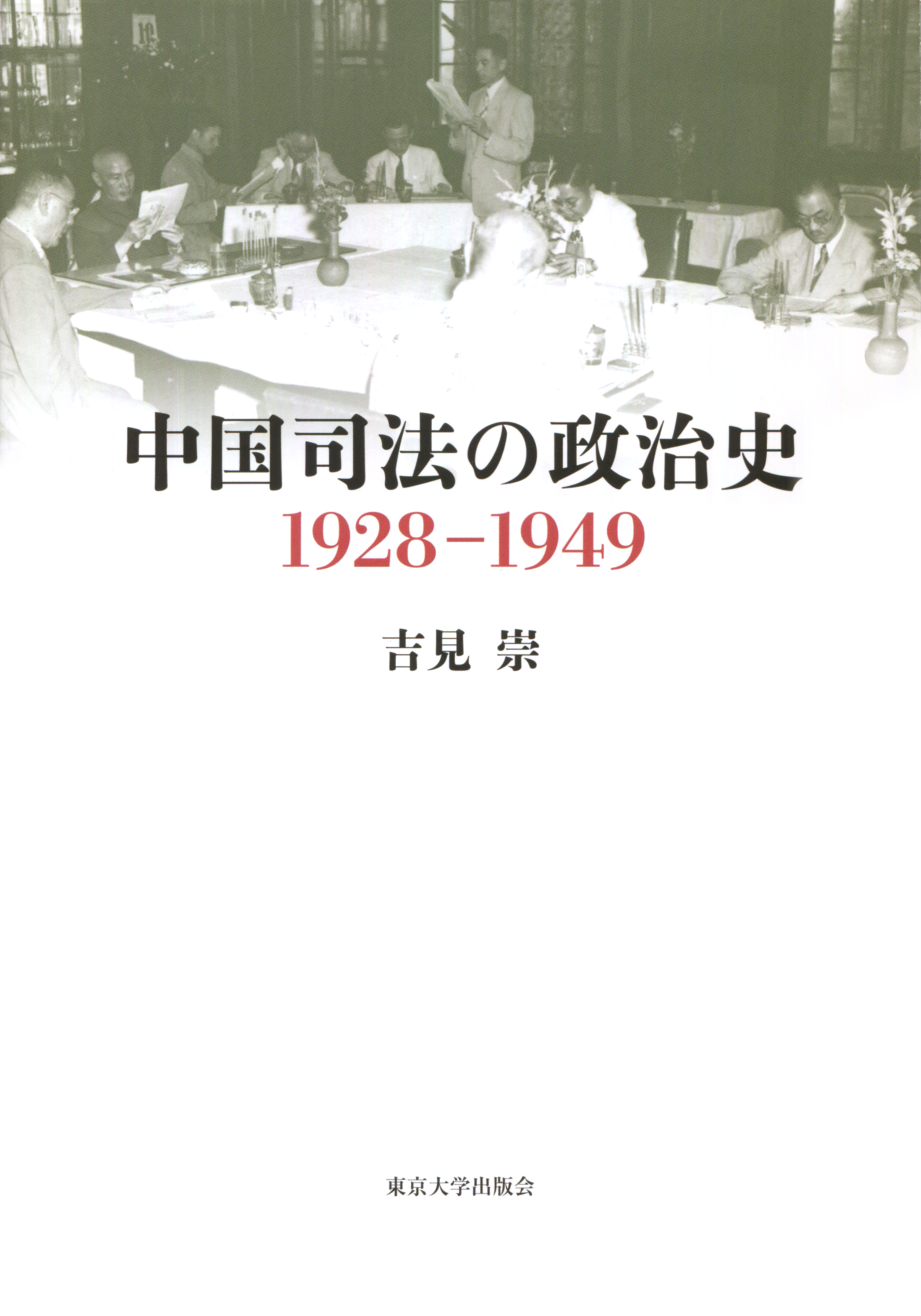

Chugoku-Shiho no Seiji-shi 1928-1949 (A Political History of Jurisdiction in China, 1928-1949)

Size

248 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

June 16, 2020

ISBN

978-4-13-026166-1

Published by

University of Tokyo Press

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

A characteristic of recent Japanese research on modern and contemporary Chinese history has been the growth of research on the history of constitutional government. The term “constitutional government” has various meanings, and if one provisionally equates it with liberal democracy, many people may wonder whether China has ever had any history of constitutional government. The reason for this presumably lies in the image of present-day Chinese politics, and people with an interest in modern and contemporary China may point to the existence of political actors such as the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang).

It is true that both of these parties are generally understood to be revolutionary parties whose political inclinations are autocratic. But as a result of the above-mentioned advances in research in recent years, it is becoming widely understood that the Kuomintang’s form of autocracy, known as “political tutelage,” is fragile and the Kuomintang itself recognized that its autocratic rule was time-limited and that the ultimate goal was the realization of constitutional government. In point of fact, in 1947, after the end of the Sino-Japanese War, the Kuomintang government promulgated and put into effect the Constitution of the Republic of China.

Drawing on the above fruits of academic research, the present book aims to elucidate the historical significance of the Kuomintang government’s transition to constitutional government by focusing on questions pertaining to the judiciary. As mentioned, past research on modern and contemporary Chinese history has not taken adequate interest in the history of constitutional government, and at the same time, in the study of political history, research on the judiciary has been neglected in comparison with the executive (cabinet) and legislature (parliament). Accordingly, in this book I set about raising some questions about research on the history of modern and contemporary Chinese politics by analyzing the relationship between constitutional government and the judiciary during the period in question. This is why this book is called A Political History of Jurisdiction in China.

Specifically, this book analyzes the three issues of independence of jurisdiction, prosecutorial reform, and physical freedom in terms of the institutionalization of the ideas of separation of powers, restraint of power, and freedom from power, each of them indispensable for constitutional government, or in terms of the process of changes in these ideas. As a result, it has become clear that the Kuomintang régime endeavoured to establish the independence of jurisdiction based on the separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers and to change the prosecutorial system based on Continental law, adopted from Japan in the late Qing, to a system based on Anglo-American law, and that with regard to the question of physical freedom, too, it attempted to introduce habeas corpus, based on Anglo-American law.

This stance of the Kuomintang régime that comes to light from the perspective of constitutional government and the judiciary may be considered to have been one that understood the idea of constitutional government and to have succeeded to a certain extent in bringing it to realization. But it must also be pointed out that modern and contemporary China has been continually adopting the separation of powers and Anglo-American law (in its judicial system), which possess universality around the world. In other words, this means that, when seeking to gain a grasp of contemporary China (People’s Republic of China), we will lapse into a one-sided understanding if we ignore this historical current and only emphasize its peculiarities.

(Written by: YOSHIMI Takashi / May 17, 2021)

eBook

eBook