Title

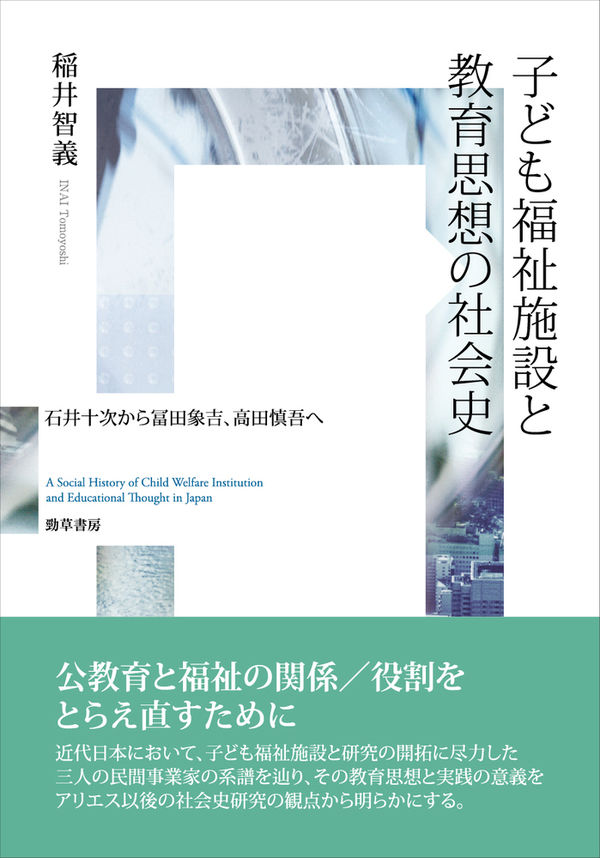

Kodomo-Fukushishisetsu to Kyoiku-shiso no Shakaishi (A Social History of Child Welfare Institution and Educational Thought in Japan - From Ishii Juji to Tomita Shoukichi and Takada Shingo)

Size

272 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

November, 2022

ISBN

978-4-326-25166-7

Published by

Keiso Shobo

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

In what way have thoughts about educating children who live in welfare institutions developed along with social conditions? To answer that question, this book makes reference to the social history of educational thought. Developed in Japan since the 1970s under the influence of historian Philippe Ariès, this field has identified problems and contradictions in modern education. This book also references Japanese studies in English-speaking countries, including Kathleen Uno's study of the social history of daycare centers and motherhood.

This book calls “child welfare institutions” those facilities that save, protect, and especially care for children on the brink of poverty or facing other crises. It traces the lineage of leaders who pioneered child welfare institutions in modern Japan. These leaders include Ishii Juji, who founded Okayama Orphanage in 1887; Tomita Shoukichi, who inherited the day-care center and night elementary school that Ishi started in Osaka City in 1909 and Takada Shingo, who researched children's problems at the Ohara Institute for Social Research, founded in 1919 from this social work. Primary sources are their writings in logs, journals, and publications, as well as newly discovered materials.

Their educational thought was to enclose (shelter and foster) children who came to the institution due to being excluded from community within the family, school, and state. Ariès wrote about this finding in his 1960 book, concluding that “family and school together removed the child from adult society.” As a scholar of Japanese history, Tanya Maus notes Ishii moved the orphanage to Chausubaru in Miyazaki Prefecture in 1912, where he built a utopian egalitarian farming community. At the time, Ishii believed that if orphans married each other and created good homes, this would build a strong state. According to a report by Tomita, parents started to show interest in their children who went to the night elementary school in the 1920s. Unstayed by the ideas of social workers who called for a governmental decree that designated day nurseries as health institutions, Tomita continued to think about saving, protecting, and educating children as an urban and labor problem in the 1930s. Tomita’s ideas, taking after those of Jacques Donzelot’s urban research, were consistently shaped by the city.

This book’s greatest significance lies in the fact that it finds in Takada’s viewing children as an economic problem an aspect that cannot be traced back to modern educational thought, and one that goes beyond putting children at the center and making mothers bear the responsibility of child-rearing. In his final years, Takada read The Conquest of Bread by the anarchist Kropotkin and believed that day nurseries existed to increase leisure among working women and make them more educated. Consequently, one challenge for the future is to reinterpret the role of public education and welfare from the point of view of leisure to rest the parent-child relationship and of anarchism.

During a break in my research, I visited Chausubaru Elementary School, which was founded in May 1946. The school is attended by children that live at the institution opened in October 1945 by Ishii’s grandson, Kojima Kouichirou. Along with the reality and remaining issues at the intersection of education and welfare now buried in history, I want to think about the training of teachers who have an understanding of social welfare and what public education ought to look like. I hope this book will offer its readers insights on children, education, and welfare.

(Written by: INAI Tomoyoshi / March 20, 2023)

Table of Contents

Preface - The educational thoughts of leaders of child welfare institutions: Issues and methods

1. Ishii Juji’s views on family and caring for children at Okayama Orphanage: How it developed from a project to save children into one to protect them

2. Ishii Juji’s idea of “national education” and education at Okayama Orphanage: How glorifying the emperor coexisted with Christian belief

[Addendum 1] Ishii Juji’s conception of the constitution and the move to Chausubaru: From an orphanage to New Education and utopia

3. Tomita Shokichi’s child-rearing project theory and the association studying relief projects: The changing relationship between the orphanage and the day-care center

4. Tomita Shokichi’s social policy theory and activities at Aizenbashi Night Elementary School: Dealing with non-attendance and making public elementary schools widespread

5. Tomita Shokichi’s theory of saving children and the interwar controversy over legislation on day-care centers: Early childhood education and child labor protection in poor urban areas and mining communities

6. Takada Shingo’s research on children’s problems and the Ohara Institute for Social Research: Education, nutrition, and self-cultivation in the “socialization” theory of saving children

[Addendum 2] The intersection between child welfare institutions and anarchism

Epilogue - Reinterpreting education and welfare

Bibliography

Afterword

Index of names

Subject index

Related Info

The 3nd UTokyo Jiritsu Award for Early Career Academics (The University of Tokyo 2022)

https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ja/research/systems-data/n03_kankojosei.html

eBook

eBook