Title

The Archaeological Journal No. 659, 2014 Kokuyou-seki Gensan-Chi Iseki No Kenkyu (The studies of prehistoric Japanese obsidian quarries)

Size

38 pages

Language

Japanese

Released

August 30, 2014

ISSN

04541634

Published by

New Science co., ltd.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

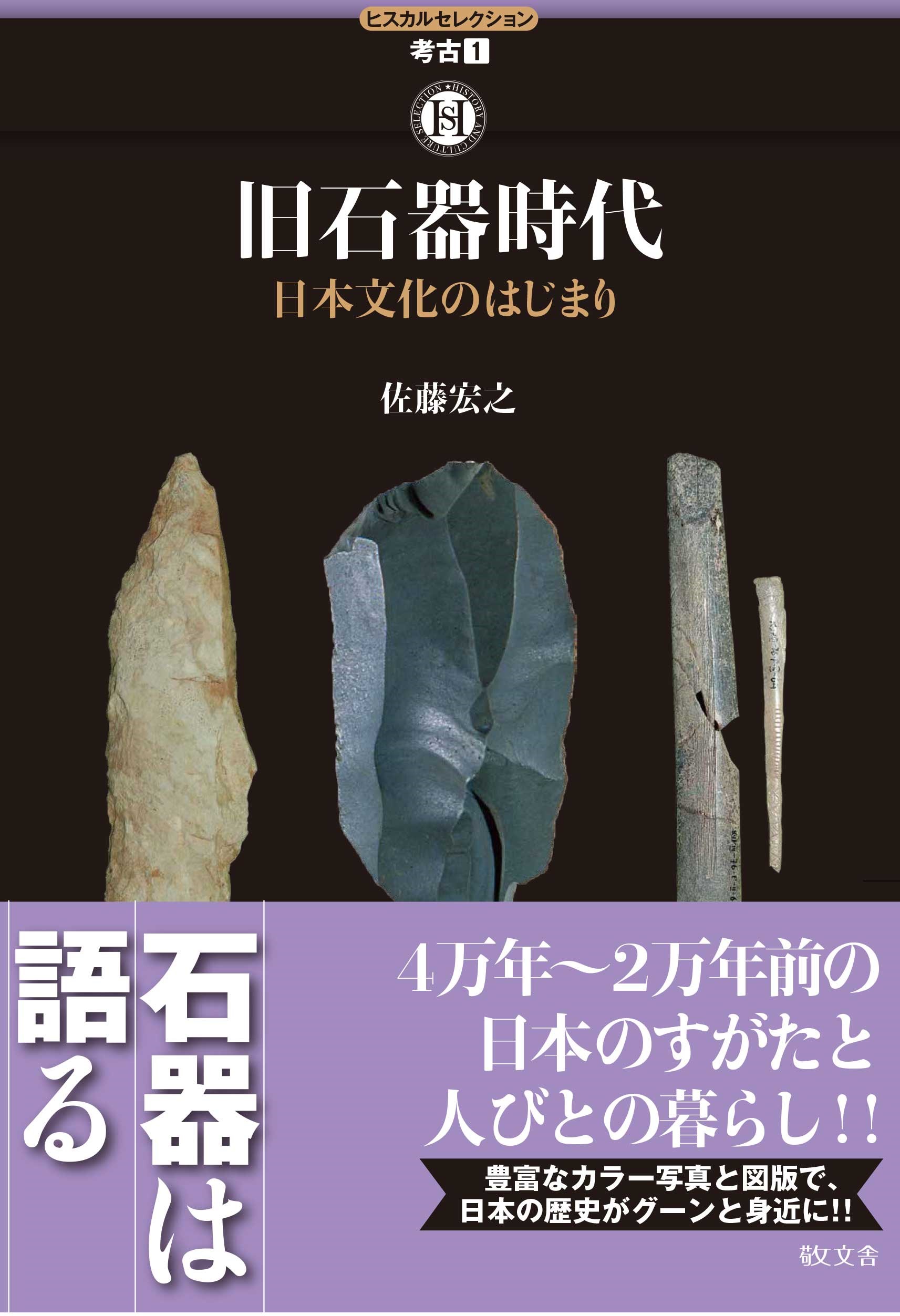

Obsidian was the chief material for lithic making throughout the Japanese Prehistory (Paleolithic and Jomon era). Obsidian, a volcanic glass formed when magma is rapidly cooled, is distributed all over the world, especially around the major volcanic belts. The exact source of obsidian can be traced by the slight differences in its mineral and chemical composition, reflecting the content of volcanic magmas that yielded the rock.

More than 80 obsidian sources have been found in the Japanese archipelago. Among these, obsidian from sources such as Shirataki (Naoe, in this volume), Oketo, Tokachi, Akaigawa (Nagasaki, in this volume) in Hokkaido, Takaharayama (Kunitake, in this volume) in northern Kanto, sites around Yatsugatke (Otake, in this volume) and Gero in central highland, Kozushima in Izu, Okinoshima in Sanin, Koshidake (Tachibana, in this volume) in northern Kyushu, have been widely distributed and abundantly found in numerous prehistoric sites.

Large obsidian sources are often located in mountainous areas because the rock frequently occurs near craters of big volcanos. In contrast, in the Upper Paleolithic (38000 - 16000 years ago), which was the era when first modern humans emerged in the archipelago, and in the Incipient Jomon era (Late Glacial, 16000 – 11700 years ago), activities of those populations were mainly around lower, flat areas such as tablelands and gentle slopes of hills. Therefore, the exploitation of obsidian by those populations should have been systematic. The climate of the era was glacial, which was basically cold and arid, and the temperature fluctuated rapidly in short cycles. As a result, people were not able to depend on plant resources, and their diets were mainly based on hunting of highly mobile middle to large mammals. As a consequence, the strategy of Paleolithic people was primary maintaining their daily lives through hunting that accompanied strategic long-distance movements in lower, flat areas, with occasional expeditions to distant mountainous areas to fetch obsidian which was necessary for their lithic material.

It is unlikely that most obsidian sources located in high altitudes were occupied all year round because of the severe glacial climate in Paleolithic. Accordingly, an obsidian source site could not be exploited exclusively by a particular group, so it was probably used as commons by different populations. As a result, Paleolithic people were attaining obsidian by directly gathering cobbles scattered around outcrops or collecting pebbles in rivers downstream.

The pattern of obsidian exploitation completely changed in the Jomon era. When the late glacial, which was the last era of rapid cold-warm fluctuations, ended, the stable and warm Holocene environment soon covered the whole world including Japan. As the major ocean currents started to flow around the archipelago, the climate of Japan changed from continental to oceanic, and under these humid and warm conditions, the forest environment developed. In the early Jomon era, the settlements consisting of a number of pit dwellings emerged. People gradually became sedentary, and their subsistence was diversified, integrating hunting, gathering, and fishing. The climate around mountainous quarries also ameliorated, enabling a group to occupy the site all year round to mine obsidian. This led to the establishment of a wide-range trading system, through which obsidian circulated among different and distant groups.

(Written by SATO Hiroyuki, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book