Title

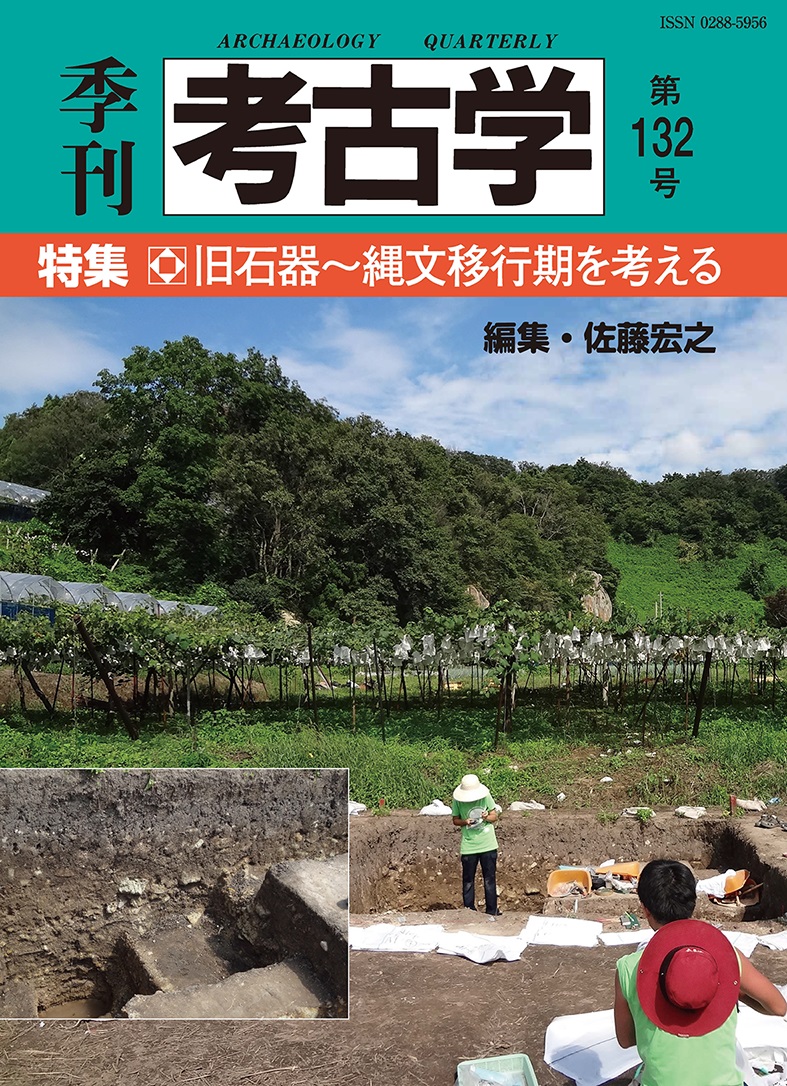

Kyusekki-Jomon Ikoki wo Kangaeru (Archaeology Quarterly issue 132: Studies of Paleolithic-Jomon transition)

Size

115 pages, B5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

August 01, 2015

ISBN

978-4-639-02367-8

Published by

Yuzankaku Inc.

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

The transitional period from the Paleolithic to the Jomon era was perhaps the most important epoch for the Japanese archipelago. It involved both changes in the natural environment and human culture. This epoch corresponds to the transition from Pleistocene (glacial) to the Holocene epoch (warm period), which is the global climate change that resulted in historical events such as the emergence of agriculture, development of civilizations and urbanization.

The glaciers lowered the sea level, and as a result, during the Upper Paleolithic period (38000-16000 ka) Shikoku and Kyushu in mainland Japan were separated from the Eurasian continent and formed the integrated landmass of Ko-Honshu (Palaeo-Honshu) Island. In contrast, Hokkaido was connected to the continent to form the peninsula (Paleo-Hokkaido Peninsula) which also consisted of the present Sakhalin and Kuril Islands. Through the Upper Paleolithic period, the archipelago was covered by the continental cold, and arid climate (Kumon, in this volume) and the eastern part of the archipelago was dominated by coniferous vegetation, whereas in the western part a mixed forest of conifers and broad-leaved trees predominated (Takahara, in this volume). The vegetation led to a scarcity of edible plant resources. Moreover, the rapidly fluctuating climate (Dansgaard-Oeschger Cycle) resulted in an unpredictable distribution of resources. The climate also forced Paleolithic people to be largely depended on hunting for their subsistence, mainly by exploiting middle to large sized mammals (Takahashi, in this volume), which had adapted to the unstable environment by forming a highly mobile pattern.

The Late Glacial period, the era of global climate upheaval, began about 15000 years ago. Because the earliest pottery in the Archipelago (Odai-Yamamoto 1 site, Aomori Prefecture, 16000 years ago) is older than the beginning of the Late Glacial period, the Incipient Jomon (16000-11700 years ago) is considered to begin at the terminal Glacial (Kudo, this volume). The regions that are considered to own pottery from Pleistocene are Transbaikal, middle Amur (Uchida, this volume), eastern and southern China (Onuki, this volume), and Japan. It is now plausible to conclude that this pottery emerged simultaneously and indigenously in each region, excep in southern China.

The Jomon subsistence pattern arose in southern Kyushu where the climate had become temperate earlier than the other regions of the archipelago, and it spread gradually to the north (Magome and Akinari, this volume). In southern Kyushu, where pottery use was habitually practiced, the use of plant resources also flourished and sedentism developed in Incipient Jomon. However, while the Jomon subsistence mode such as implements (Hashizume, in this volume; Oikawa, in this volume), exploitation of material for implements, and the emergence and stabilization of settlements advanced gradually through Incipient Jomon era in the mainland, in Hokkaido, there continued a mobile subsistence pattern since Paleolithic period, and there the fully-developed Jomon society appeared only after the Early Jomon era (Fukuda, in this volume).

The early Jomon era of the early Holocene epoch was humid and warm, and the forest environment developed, and maritime resources were abundant in this climatic condition. Rich resources enabled the establishment of a mature Jomon society throughout the Archipelago (Taniguchi, in this volume), which possesses the sedentary subsistence pattern based on diversified resource exploitation such as hunting, gathering (Sasaki, in this volume) and fishery (Ogasawara, in this volume). It is unlikely that Jomon culture has its origin outside the Japanese Archipelago (Anzai, in this volume).

(Written by SATO Hiroyuki, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2017)

Find a book

Find a book