Title

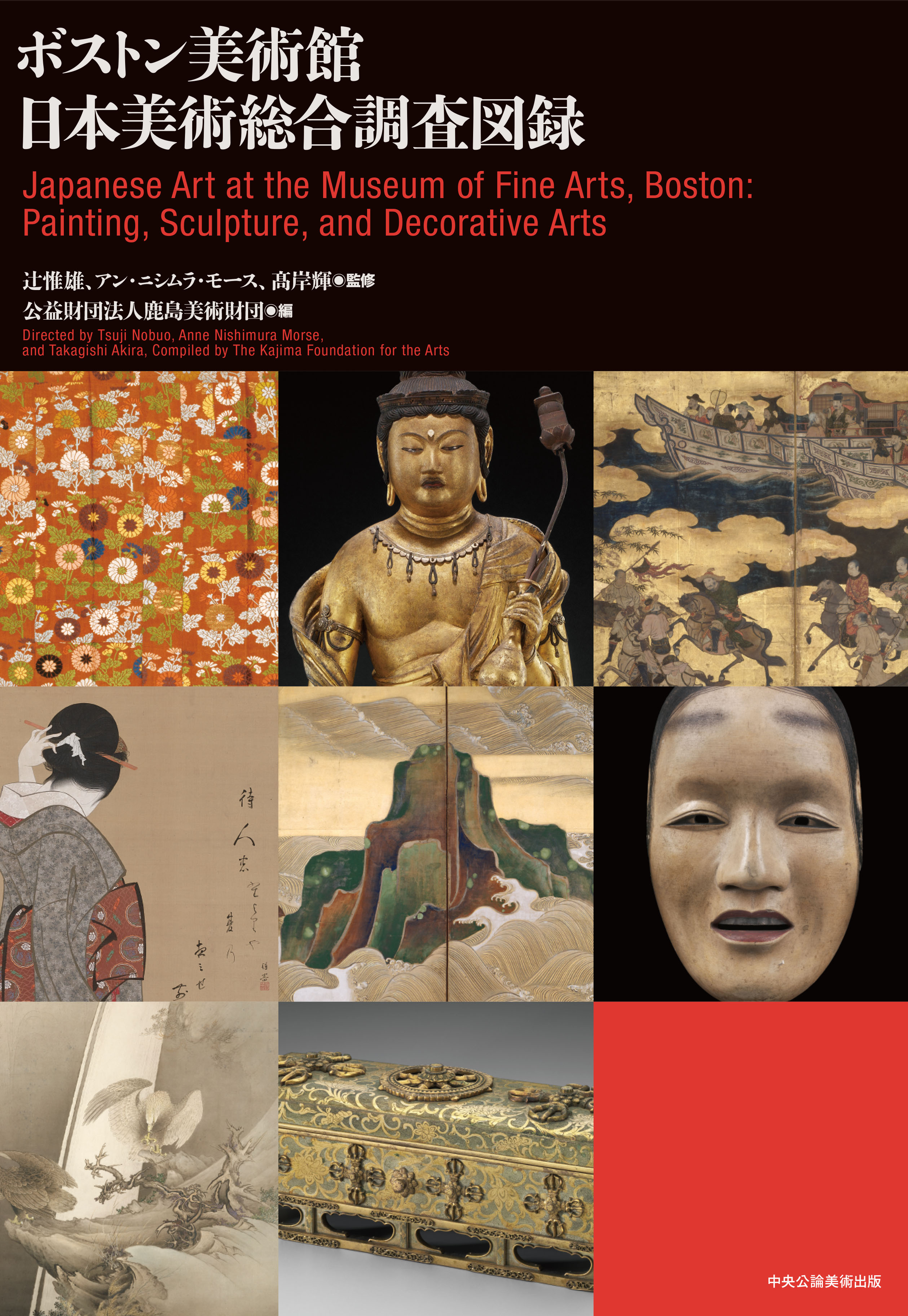

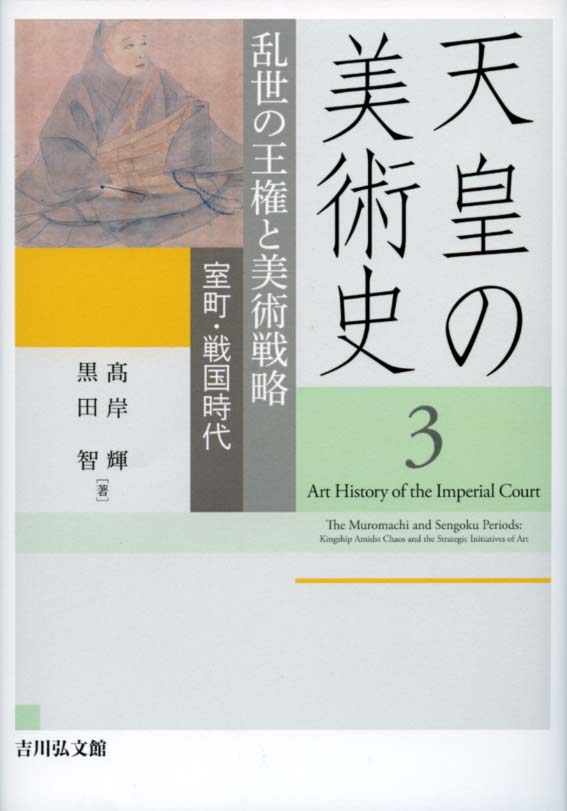

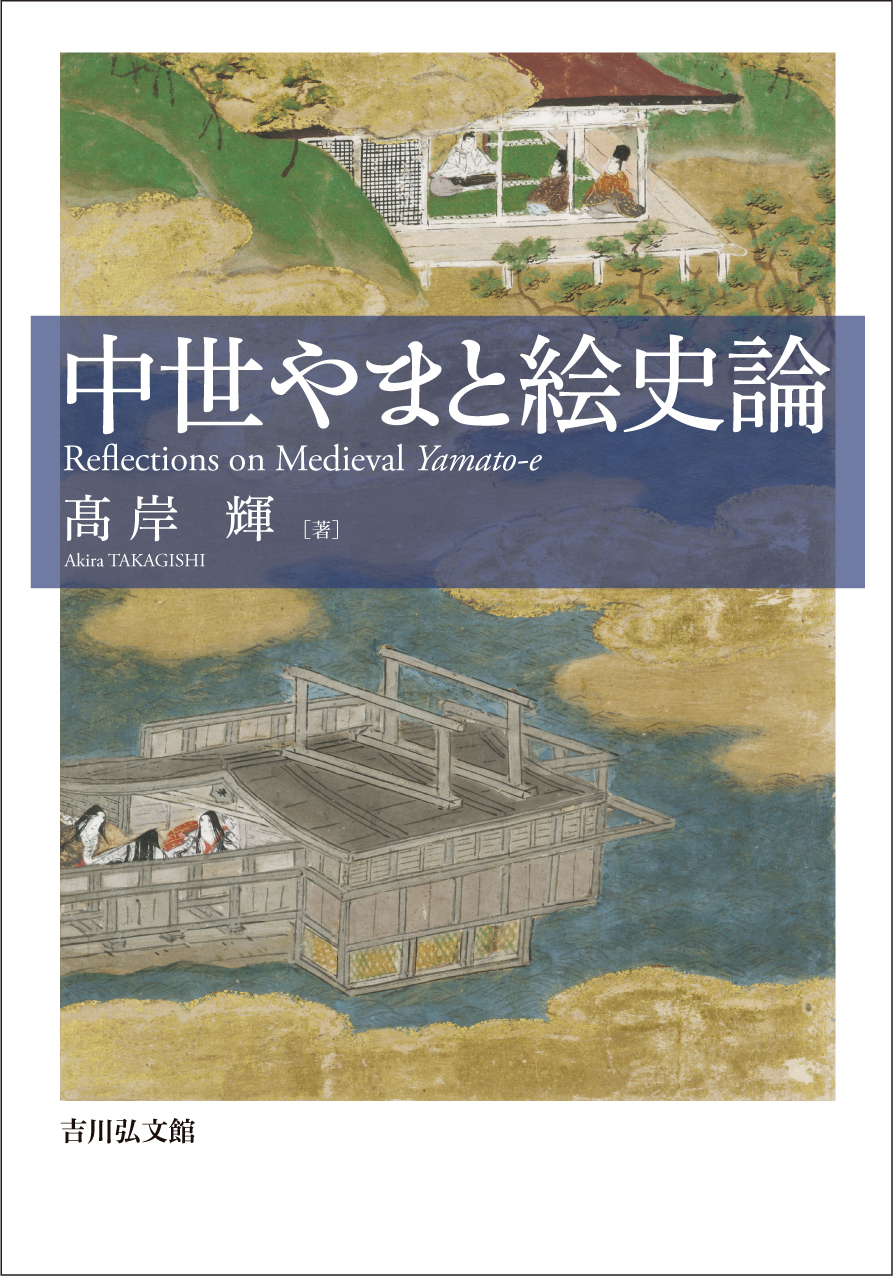

Chusei Yamato-e Shiron (Reflections on Medieval Yamato-e)

Size

444 pages, A5 format

Language

Japanese

Released

February 25, 2020

ISBN

9784642016643

Published by

Yoshikawa Kobunkan

Book Info

See Book Availability at Library

Japanese Page

Yamato-e (“Japanese-style painting”) refers to a style of painting originating in polychrome paintings popular in China during the Tang period, which were introduced to Japan and developed in the aristocratic society of the Heian period into diverse genres such as folding-screen paintings, illustrated handscrolls, portrait paintings, Buddhist paintings, and so on. Together with the kana syllabaries and 31-syllable waka poetry, yamato-e formed the foundations of Japanese culture at the time and was carried over to the medieval period (12th to 16th centuries). As the centre of political power shifted from court nobles to warrior families, the exponents of yamato-e also changed from the former to the latter. Just as the brackish waters at a river mouth where fresh water and seawater intermix nurture a rich ecosystem, so too could the aesthetic sensibilities of multiple tiers of rulers be said to have mutually infiltrated one another and added vitality to contemporary culture. The appeal of medieval yamato-e lies in the fact that, by either coming into conflict or harmonizing with each other, repeated revivals of the classics and a new visual sense such as that of India-ink paintings introduced from China constantly continued to bring changes to style and modes of expression.

In this book, I endeavour to approach works of art, painters, and their patrons by several different methods. Here I would like to mention three examples. First, in “The Composition of the Yamai no Sōshi” (pt. I, chap. 3), I analyze the composition of this illustrated handscroll. Twenty-one scenes from this handscroll about strange maladies and disabilities have survived. Focusing on the buildings and on the postures of the people depicted in this handscroll, I drew some additional lines and classified the illustrations into six patterns. By this means there are thrown into relief the typical methods whereby painters of the late Heian period pursued visual effects, such as arranging human figures in triangles to provide a sense of stability and contrasting the relative density of space by dividing the painted surface with diagonal lines.

Secondly, by extracting statements by patrons and painters from diaries, letters, narrative tales, and other written sources, I inquire into their assessments of paintings and their ideas about painting. In “A Handscroll Enthusiast’s Comments on Illustrated Handscrolls” (pt. I, chap. 2), I take up statements by the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa. When Minamoto no Yoritomo came from Kamakura to visit Kyoto, Go-Shirakawa tried to show him some of the illustrated handscrolls in his collection on the assumption that there would be no comparable works of art in the Kantō region. But Yoritomo politely declined his offer so as to avoid forming any relationship with Go-Shirakawa based on superiority due to cultural differences. In “Tosa Mitsunobu’s Communication” (pt. III, chap. 5), I give examples of a Muromachi-period painter who, after having produced a Buddhist painting or illustrated handscroll on the order of a court noble or a temple, sometimes offered to return the payment for the painting or else firmly refused to accept any payment. It becomes clear that for a painter the execution of a painting was not just a means of livelihood for which he sought monetary compensation but was also a way of giving expression to his own beliefs. It may be possible to see in this signs of a shift from artisan to artist in a painter’s self-awareness.

Thirdly, I compare different styles. In “The Area Where the Dōjōji Engi Was Produced” (pt. IV, chap. 6), I extract several faces depicted in the illustrated handscroll Dōjōji engi and point out that they have close similarities with faces depicted in two illustrated handscrolls produced in Nara in the 1530s. Since the date and place of composition were thus confirmed, the actual patron of these works also came to light.

I first set foot into the world of art history because I was drawn by the beauty of modes of expression in art works and their marvelous techniques. By scrutinizing the art works themselves and sometimes perusing outside historical sources, the raw movements of people’s minds and former aspects of society become apparent. In recent years, the public accessibility of not only textual sources but also digital images of cultural assets on the Internet has been rapidly improving. By making use of this new technology, I hope to delineate an even more vivid history of art in the future.

(Written by TAKAGISHI Akira, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology / 2020)

Find a book

Find a book