Sensor detects odor from human sweat using mosquito membrane protein Artificial cell membrane-embedded device mounted onto robot

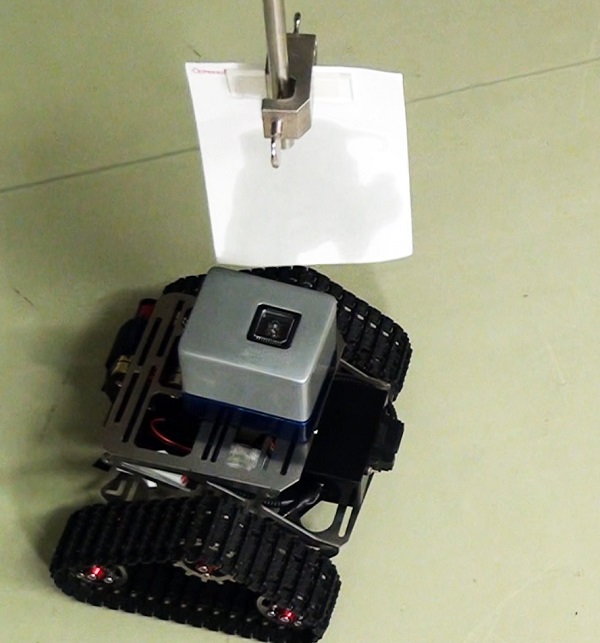

A locomotive robot equipped with an odor sensor employing a mosquito's olfactory receptor

The robot moved toward the right when a filter paper immersed in octenol (an odor component of human sweat) was held over its odorant sensor.

© 2016 Shoji Takeuchi research group.

A University of Tokyo research group and their collaborators developed an odor-detecting sensor made from a membrane protein found in mosquitoes called an olfactory receptor, which responds to the smell of human sweat, that they embedded in an artificial cell membrane. The researchers succeeded in getting a mobile robot mounted with the sensor to kick into motion when detecting the smell given off by a particular substance. Such applications of the sensor may one day play a vital role in search and rescue operations during disasters.

Researchers in various countries have developed sensors that detect odors, but these devices pale in comparison to a living creature’s organ in terms of compactness, sensitivity, and selectivity in distinguishing smells.

The research team led by Professor Shoji Takeuchi at the University of Tokyo Institute of Industrial Science, Researcher Nobuo Misawa at Kanagawa Academy of Science and Technology (KAST), and their collaborators at Sumitomo Chemical embedded the olfactory receptor—a membrane protein found in the antenna of a mosquito, which responds to human sweat odor—in an artificial cell membrane mimicking nature by having a lipid bilayer, which was formed using a method built on the scientists’ earlier research.

The olfactory receptor used in the current study responds only to a substance called octenol, an odor component of human sweat, and changes the membrane’s conductivity, or the ease with which electricity passes through it. A mosquito identifies human odor by detecting this change in electrical current.

The researchers installed the sensor, the membrane embedded with the mosquito protein, into a small wireless device and mounted it on a locomotive robot; they succeeded in demonstrating that when octenol was released in the air around the robot, it responded by moving.

The team aims to develop practical applications for the sensor that will help rescuers search for the missing in disasters and other situations when visual confirmation is difficult.

“Using the olfactory receptors of insects apart from the mosquito presents possibilities for applying them to detect illegal drugs and explosives,” says Takeuchi. He continues, “The life of the sensor currently stands at about one hour; we are aiming to extend this to around half a day.”

The current findings are based on results obtained from a project commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), Japan. This research was carried out as a collaboration among the University of Tokyo, KAST, and Sumitomo Chemical. The research outcome was delivered as an oral presentation during the MicroTAS 2016 international conference held in Ireland in October 2016.

Press release (Japanese)

Paper

, "Odorant Sensor Using an Insect Olfactory Receptor Reconstructed in Artificial Cell Membrane", The 20th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences (Micro Total Analysis Systems 2016) Oral presentation: 2016/10/10 (Japan time)

Links

Institute of Industrial Science

Department of Mechano-Informatics, Graduate School of Information Science and Technology

Department of Life Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Shoji Takeuchi Lab, Institute of Industrial Science

Sumitomo Chemical Cell Science Group, Environmental Health Science Laboratory, Sumitomo Chemical