The relationship between disaster, gender and poverty

This is a series of articles highlighting some of the research projects at the University of Tokyo registered under its Future Society Initiative (FSI), a framework that brings together ongoing research projects that contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

FSI Project 010

When disaster strikes or danger approaches a community, does being male or female result in a different amount of harm experienced and impact recovery? This question forms the basis of a project by Professor Mari Osawa who was inspired by two recent calamities that struck Japan.

The first is the economic crisis of 2008, the Lehman shock. Many advanced countries took several years before they made a V-shaped economic recovery, but Japan remained in the doldrums, reflecting the fragility of the economy.

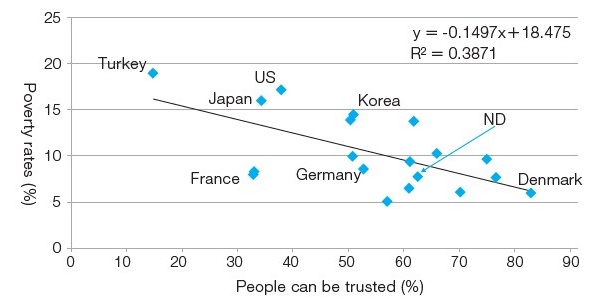

In societies where the relative poverty rate is high, general trust is low. Japanese society belongs to that category. Japan has the highest relative poverty rate amongst developed countries next to the U.S., and people who say “I trust others” is only 30 percent. Overall trust is also related to the effectiveness of ICT investment. The ability to trust others, so that superiors can trust their subordinates for a conducive corporate environment, results, for example, in higher returns on ICT investment. There is a pressing need to build a trusting society to realize Society 5.0, the future society where open innovation is highly valued.

The other was the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. The pace of recovery efforts has been slow, and even though eight years have passed, revitalization is still incomplete. This shows that Japanese society is also vulnerable to natural disasters.

The fragility of Japanese society is not unrelated to gender inequality. The Japanese tax system and social security system, even today, are based on the concept of a husband employed for life who will support his wife, which means that people such as single mothers who don’t fit that mold are at a disadvantage. Osawa said, “While male temporary workers in the manufacturing industry were laid off during the Lehman shock, many women who were taking care of the elderly were sacrificed during the earthquake. These are both gender issues.”

Research so far has shown that women make up the majority of casualties during a disaster, and that the larger the gender inequality in the country, the more women are harmed. For example, in the Islamic world, women who are not allowed to go out alone are certainly not allowed to swim in public, which means that in times of floods or other disasters, women who can’t swim or have no sense of direction often become victims. Of course, this is not a problem unique to Islamic areas.

Furthermore, in addition to the correlation between gender and disaster, this project also explores the relationship between the poverty rate and general trust. In short, the findings show that a society with gender equality has a lower poverty rate and higher level of trust, and corporations’ information and communication technology investment has a higher rate of return.

Amongst developed countries, Japan’s poverty rate is one of the highest, and the main reason for this is the large gap in gender equality. Said Osawa, “In order to help Japan’s economy recover and become resilient to disaster, now more than ever we must have gender equality.”

SDGs supported by this project

Professor Mari Osawa | Institute of Social Science (at time of interview, now emeritus professor)