Revisiting Ancient History in Familiar Themes | UTOKYO VOICES 018

Revisiting Ancient History in Familiar Themes

Many historians were enthralled by history as children, but not Inada. Inada didn’t watch NHK’s Taiga Dorama (annual year-long historical dramas) and didn’t read historical novels. She loved mystery novels and eventually turned to history as a discipline for solving mysteries using reasoning and logic. She found history fascinating, recalling that, “by high school I wanted to be a historian or an archaeologist.”

As a university student, Inada’s imagination was captured by a class she took in which the professor relativized Japanese history by comparing it to that of China. “The Yamato Imperial Court created the ritsuryo system (a system based on the philosophies of Confucianism and Chinese legalism) by copying China’s (Tang Dynasty) system and I was curious about what the Court decided to incorporate and what it decided to leave out.”

Inada focused on mourning and funeral rites relating to mogari (delayed interment), emperors’ funerals, mourning, mourning dress, and government officials’ burial grounds in particular. Under China’s ritsuryo system, mourning and funeral rites were carefully regulated, and although Japan’s Yoro Ritsuryo Code (code promulgated in the Yoro period) copied this meticulously, there were some differences. While studying for her Master’s and Ph.D., as well as during subsequent research work, Inada analyzed these differences and identified the characteristics of mourning and funeral rites that Japan’s ritsuryo system aimed for.

At that time, hardly anyone else was researching mourning and funeral rites in ancient history. “There seemed to be a belief that ancient history is a discussion of high affairs of state. But actually, mourning and funeral rites are experienced by everyone, including the people of ancient times. My research made me to want to find out even just a little more about the lives and feelings of the people who lived back then.” With not much in the way of prior research and reference materials to make use of, Inada approached her research as a detective approaches a mystery. Careful reading of the ritsuryo enabled her to put together a picture of the rites practiced in those days.

Inada subsequently realized that even though Chinese culture came to Japan via the Korean peninsula, a research focus on China and Japan meant that the Korean peninsula was overlooked. This lack of focus on Korea came from not being able to read Hangul, so she went to Korea to further her research. “My horizons expanded hugely once I learnt to read Hangul. I revisited Korean history based on my knowledge of ancient Japanese history and can now argue that the mourning and funeral rites in the three regions are actually linked.”

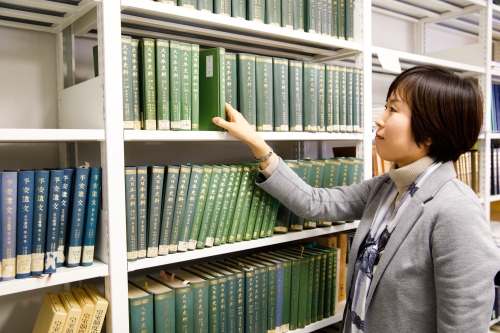

Inada continues her research while involved in compiling the Shosoin Monjo Mokuroku (a catalog of records relating to the Shosoin Documents) at the Historiographical Institute. She is particularly interested in recreating the mourning and funeral rites of bygone days. “In China, there is a collection of ancient documents discovered in an underground tomb known as the Turfan Documents, and these documents include lists of burial items. The items are listed in the same order: headdress, clothes, footwear, and so I assume that this is the order in which the body was ritually dressed.” There are no records of rituals, but by focusing on the records it might be possible to reconstruct them. Inada thinks that it might be possible to apply this approach to ancient Japanese history.

As more people show an interest in researching mourning and funeral rites, Inada’s presence, as a forerunner who paved the way for such research, is huge. Inada is emphatic: “Most people think that rituals such as funerals are traditional and do not change over time. However, the more research we do, the more likely we are to discover a world completely different from the one we imagined. So from the standpoint of questioning what according to common knowledge are taken to be “traditions,” I find my current research to be fascinating.”

Restoration of the Shosoin Monjo accounts for a large portion of Inada’s work and research. This tape measure is used to determine the size of scrolls that have become separated. Via these measurements, the locations of the joints are confirmed, and the scrolls are restored to how they were when created during the Nara period.

Many people think that rituals such as funerals are traditional affairs that haven’t changed over time. However, this is a misconception. By looking back through history we can see a completely different world. [Text: “Dento” wo utagae (Question “traditions”)]

Natsuko Inada

Natsuko Inada left university in 2004 after receiving credits towards a Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, the University of Tokyo and was appointed as an assistant at the university’s Historiographical Institute. Inada was appointed an assistant professor in 2007 and obtained a Ph.D. (Doctor of Letters). Inada was responsible for the Part 1 of the Dai Nihon Shiryo (a collection of historical documents) and Shosoin Monjo Mokuroku (a catalog of records relating to the Shosoin Documents). In 2009 Inada spent 10 months in Korea engaged in research. Her research interests lie in East Asian cultural products, and in mourning and funeral rites in particular. She is the author of Nihon Kodai no Mosougirei to Ritsuryosei (Ancient Japanese Mourning and Funeral Rites and Ritsuryo System) (published by Yoshikawa Kobunkan in 2015) and co-author of A New Interpretation of Da-Tang Yuan-ling Yi-zhu (Funeral Rites for Tang Emperor Dai-zong: New Interpretation) (published by Kyuko Shoin in 2013).

Interview date: December 14, 2017

Interview/text: Hiroshi Kikuchihara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.