Listening to people from developing nations who have no voice|UTOKYO VOICES 042

Listening to people from developing nations who have no voice

With an interest in social issues since middle school, Professor Ohgushi majored in politics at university. Initially, he was interested in Japanese politics, but became drawn to international politics in the course of his studies. When he started graduate school, he decided to research the politics of developing nations.

“The biggest reason was that there are people there, in the places that are suffering most, who are being oppressed and cannot make their voices heard.”

During his doctoral research, he flew for the first time in his life, at age 26, all the way to the other side of the world, to Peru. He stayed there from 1983 to 1986 researching military politics.

“If you don’t immerse yourself in the local community, you won’t be able to truly understand what people think about things, and how they behave. I made a lot of friends over there, which allowed me to get a deeper understanding of how they thought, and this went on to form the foundations of my research.”

Ohgushi is currently researching “transitional justice.” This deals with issues of human rights violations, war crimes committed during armed conflicts, and violations of international humanitarian laws during the period following the end of a dictatorship or military government.

Since the 1980s, in countries likes Argentina and Chile that used to be military dictatorships, the people who suffered, or the families of those who were even killed, have striven to launch lawsuits against the military leadership or soldiers. However, these victims have brought their suits despite fears that they may suffer in the event of a coup or civil war, as the influence of the military remains strong even after the transition to democracy.

What these victims have sought in these lawsuits is truth, in both the macro and micro sense. The macro truth is for truth commissions to show society a comprehensive view of what happened during dictatorships, while the micro truth is to explain what happened to those who were forcibly made to disappear and killed, and to mourn them.

These initiatives in Latin America were some of the first anywhere in the world. Later, following the war in former Yugoslavia and the Rwanda massacres, international public opinion, led by the United Nations, turned towards not allowing serious violations of human rights to go unpunished, and in 1998 the Rome Statute to establish the International Criminal Court was adopted.

“However, there’s a lot of criticism about lawsuits themselves. There are strong voices from conciliatory pacifists, who prefer reconciliation above all. So my research is based on my views that we need to put what the victims want first and foremost.”

So, starting in 2001, Ohgushi has visited Peru and Colombia. Both countries have been areas where anti-government guerillas, government public order squads, and private organizations connected with these squads have carried out torture and murder on a wide scale against general civilians. In the summer of 2018, he visited Bosnia, which saw great numbers of deaths and refugees, and violations of human rights, in its civil war from 1992 to 1995. There, he conducted interviews on topics such as “If your aggressor appeared now, and showed sincere regret, how would you respond?”

Ohgushi does have some regrets about having to ask these victims about experiences too horrible to put into words. However, he believes letting the world hear the voices of people who lived through the reality of unimaginable human rights violations teaches valuable lessons for all those living in almost all other countries who believe that such horrors could never affect them. This is why he continues to push ahead with this research.

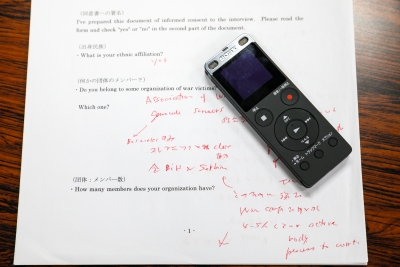

IC recorder and questionnaire form

Once, when interviewing someone connected with a military government about the inside story, Ohgushi was told, “I’ll tell you more if you stop recording,” so he stopped using recorders. However, he has done a lot of interviews with human rights violations victims lately, so started using this IC recorder during his interviews in Bosnia in 2018.

“Humanism”

Ohgushi wants to rebuild respect for all those people whose experiences are beyond description, who have had family or relatives taken away and never seen again under military regimes or dictatorships. The underlying base of his research is the words of Emeritus Professor Yoshikazu Sakamoto, “Everything goes back to human rights.”

Profile

Kazuo Ohgushi

Served as assistant professor in the Faculty of Literature and Social Sciences, Yamagata University, and professor at International Christian University, then appointed as professor in the Faculty of Law, University of Tokyo, in 1999. Served as president of the Japan Association for Comparative Politics, president of the Japan Association for Latin American Studies, and president of the Kawasaki Peace Museum Consultative Committee, among other positions. Research areas include Latin American politics, comparative politics, and human rights issues, with a focus in recent years on transitional justice. Publications include Armed Forces and Revolution: A Study of Peru's Military Government (University of Tokyo Press, 1993), which won the Masayoshi Ohira Memorial Prize, and Politics and Violence in the 21st Century (as editor; Koyo Shobo, 2015).

Interview date: November 28, 2018

Interview/text: Hiroshi Kikuchihara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.