Viewing society through the lens of disability|UTOKYO VOICES 043

Viewing society through the lens of disability

When Professor Hoshika was just one year old, he fell ill with pediatric cancer. At age five, he lost his sight, but apparently was still as active and lively as a child could be.

His choice to attend a regular public school for elementary, junior high, and high school was treated as unprecedented. “Both my parents and the schools were in a panic,” he remarks with a laugh. “It didn’t feel special to me, but to the world around me, it was this major decision. And I couldn’t help but be aware of that,” he reflects.

He majored in sociology at the Faculty of Letters, the University of Tokyo and wrote his thesis on theories of volunteering. In his master’s program, he learned about the field of Disability Studies and, “thought that pursuing work as a researcher might not be a bad idea.”

Disability Studies is a field that explores the difficulties facing individuals including those with disabilities in terms of phenomena that occur through interactions with society. This is a completely different approach from that of medical science, where disabilities are considered difficulties that arise from physical disorders.

For example, some people have difficulty sitting through the entirety of a university class period (105 minutes). Everyone has things to which they are not well suited, but the result is that those who fall into a category that conforms with society’s rules—the majority—can live their lives without difficulty, whereas those who do not fall into such a category—the minority—must deal with inconvenience and difficulty in their day-to-day lives. Hoshika regards the idea of disability as one way to become aware of this social imbalance. By his linking the interest in society that he had had since his high school days with the reality he knew as an individual with a visual disability, the theme of his research was cut out for him.

His book “What is Disability?: Toward a Social Theory of Disability,” based on his doctoral thesis, received a favorable reception for challenging conventional conceptions of disability, and it formed the foundation of his career as a researcher.

Hoshika also points out that demands for social conformity imposed upon women, members of the LGBT community, foreigners, and others whose characteristics and attributes make them minorities could also constitute a kind of barrier. While anyone can become a member of either the majority or the minority, “the fact that a gap has come into being is itself a disability,” he says.

Hoshika belongs to the Center for Barrier-Free Education, which aims to create a society in which people with diverse characteristics can live together. The center is creating a variety of educational content for companies and society at large, such as the “barrier-free mind” education and training initiative being spearheaded by the Cabinet Secretariat, and their efficacy is being investigated as well. With the 2020 Tokyo Olympics just around the corner, these projects are especially pertinent from the perspective of legislation and societal needs.

However, the phrase “barrier-free” is originally associated with construction, and some complain that it lends itself too much to ideas of physical barriers, the type easy to depict in pictures. Based on his own ideas about including people from all walks of life and correcting the various social ills and inequalities that exist so that society is welcoming for everyone, “I think we should just use the term ‘diversity,’” says Hoshika.

He is currently in the process of laying the groundwork for translating theory into actual social implementation. “Getting actual feedback from society adds value to my theoretical research,” Hoshika says.

To what extent can we increase the number of people who understand diversity? “We can dare to dream,” says Hoshika, his composure showing even as he reveals his desire to see diversity spread far and wide.

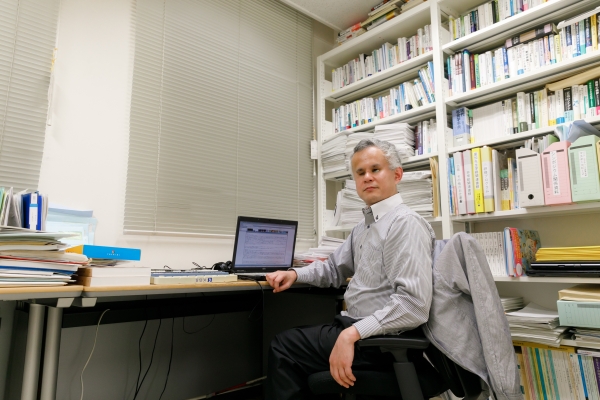

Braille display

A braille display connects to a computer and displays in braille the textual data on the screen where the cursor is. This item is indispensable to Hoshika. He combines this with software that reads words aloud to confirm the content.

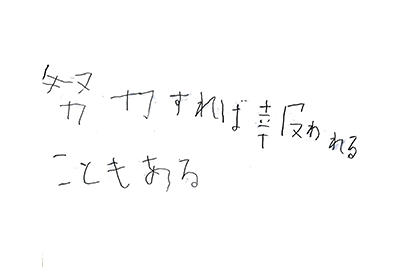

[Text: Doryoku sureba mukuwareru kotomo aru. (“Good things can come to those who work hard.”)]

These words were spoken by one of Hoshika’s junior high school teachers. That his teacher said good things “can” come somehow resonated with him. Maybe from that time Hoshika felt uncomfortable with the common tendency to ignore factors like the environment and place all of the burden on one’s individual effort.

Profile

Ryoji Hoshika

Graduated with a Ph.D. in Sociology from the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology at the University of Tokyo. Worked as a project research associate at the University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology before his current post. Primary fields of research include the social theory of disability, citizenship and identity for persons with disabilities, and disability equality and reasonable accommodation, etc. Serves on a number of national and private committees related to disability policy, and also teaches courses to educators on “barrier-free mind” education, a joint project with the Olympic and Paralympic Economic Conference, from the perspective of promoting the channeling of advanced knowledge on disability and diversity to society, among other endeavors.

Interview date: November 28, 2018

Interview/text: Yukiko Kato. Photos: Takuma Imamura.