The Science of Buddhism — exploring the historical and conceptual roots of Buddhism|UTOKYO VOICES 054

The Science of Buddhism — exploring the historical and conceptual roots of Buddhism

In the late 1990s, Associate Professor Baba was backpacking through Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, where the variant of Buddhism known as Theravada Buddhism is followed. A defining characteristic of Theravada Buddhism is the prevalence of words derived from Buddhist literature rendered in Pali, one of the ancient languages of India.

Today, Pali is a dead language, not spoken by anyone in India. “Pali is essentially an imported language that took root in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, much like classical Chinese in Japan, or Latin as the basis of the modern English language,” says Baba. “I was attracted to the idea that the history of Buddhism could affect the evolution of language.”

The ancient Japanese phrase ko-un-ryu-sui, which translates as “floating clouds, running water,” is an adage saying that apprentice monks should travel widely and experience different cultures and environments as part of their training. This describes perfectly the pilgrimages undertaken by Buddhist monks in days gone by, as a result of which a vast international Buddhist network was created, stretching from India across the whole of Asia.

Having experienced the amazing reach of Buddhism first-hand during his travels, Baba was inspired to write his doctoral thesis on the science of Buddhism: specifically, an empirical study of the social impact of Theravada Buddhism as a cultural phenomenon. “I got some pretty strong feedback from senior staff in my department, who said I had three different topics that weren’t properly linked together.”

Baba continued to ponder the issues raised in his thesis night and day, even as he worked as an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo and spent time studying at the University of Cambridge in 2006. The turning point came the following year, when he was traveling in Siena in Tuscany, with its beautifully preserved medieval streetscapes, after delivering a presentation at a university in Naples.

“All the time I was traveling, I mulled over my thesis,” recalls Baba. “And then came a pivotal moment when I was sitting in a café overlooking the magnificent Piazza del Campo in Siena. The moment I pulled out my pen and notebook, the solution to the problem came to me. I privately call it my ‘Siena miracle,’ because that moment delivered me the logical structure that would become the central crux of my thesis.”

Having readied himself and gained the confidence to debate fiercely with other scholars around the world on an equal footing, after returning to Japan, he published The Development of Theravāda Buddhist Thought: From the Buddha to Buddhaghosa (Shunjusha), the first book to ever tackle this subject matter.

Baba next turned his attention to a study of the very earliest Buddhist teachings. In order to find out more about the roots of Buddhism, he compared Buddhist literature written in early languages such as Pali and Sanskrit, looking for the oldest components — a process similar to analyzing a gene sequence for key genetic information.

He then started to explore the early Buddhist philosophies in more depth, and discovered important insights into the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha in ancient India via a historical reading of Buddhist literature. Through critical analysis of the literature he was able to discern the broader historical context of the texts and attempt a more philologically authentic reading of the underlying meanings. In 2018, Baba published his conclusions as Shoki bukkyo — Budda no shiso wo tadoru (Early Buddhism — Tracing the Teachings of Buddha) (Iwanami Shoten).

Baba’s “Siena miracle” was a transformational time that catapulted him into a fully-fledged research career. His work shows us that there is much to be learned from studying the evolution of Buddhist teachings and Buddhist ideas.

“Modern society, both in Japan and around the world, is more openly divided than ever before,” notes Baba. “If left unchecked this will only lead to more unrest and inequity between people. But we can turn it around by trying to restore trust and respect between people. Once a solid relationship or network is established, it can grow very quickly, as the history of Buddhism has shown.” Buddhist disciples of old did not bind themselves to one place or one school, but exposed themselves a wide range of teachings. Baba is convinced that people with this way of thinking coming together and forming the core of a network will build the next era.

A set of scriptures in the Pali language, published with the assistance of the Royal Household of Thailand and donated to the University of Tokyo in 2008.

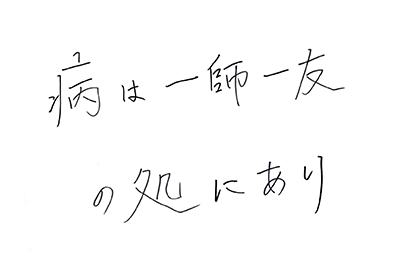

[Text: Yamai wa isshi ichiyu no tokoro ni ari (“Illness is born of having just one master, one friend”)]

This old Buddhist saying essentially means: do not limit yourself to a single master or a single friend; the more people you meet, the more you learn. One of the key tenets of Buddhism, it is also central to Baba’s academic approach.

Profile

Norihisa Baba

PhD (literature), University of Tokyo Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, 2006. Assistant professor at University of Tokyo Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, research associate at Darwin College, University of Cambridge, then visiting research fellow at the Ho Center for Buddhist Studies, Stanford University. Then took up post as associate professor at University of Tokyo Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia in 2010 specializing in Buddhist studies. Major awards include Japanese Association for South Asian Studies Award, Japanese Association of Indian and Buddhist Studies Prize, Toho Gakkai (The Institute of Eastern Culture) Award and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Prize. Major publications include The Development of Theravāda Buddhist Thought: From the Buddha to Buddhaghosa (Shunjusha) and Shoki bukkyo — Budda no shiso wo tadoru (Early Buddhism — Tracing the Teachings of Buddha) (Iwanami Shoten).

Interview date: January 8, 2019

Interview/text: Hiroshi Kikuchihara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.