Living a happy life despite illness|UTOKYO VOICES 071

Living a happy life despite illness

Professor Kasai says that when he was a boy, he was very shy and lived life in a constant state of anxiety. He saw life as difficult, and does not recall being passionate about anything.

Things continued this way until he entered high school and consulted his mother and friends about what path he should choose for his future. They told him that he was good at listening to what others said. Upon doing some research, he discovered an occupation called psychiatry. He read a book entitled Man’s Search for Meaning by the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, and thought, “This is it!”

Kasai was not good at the sciences, so he began studying “like an ascetic” in his second year of high school, and did well, being accepted by the University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine. After starting there, he underwent an amazing change. He says, “I became like a leader, as if my life before that had been a lie,” and this included serving as the head of the braille club and badminton club.

His analysis is that through the various experiences that he had, he was able to eliminate the negative view he had of himself, or “self-stigma.”

At the school, he looked up to the professor of anatomy, Takeshi Yoro. While Kasai had believed that psychiatry was solely about dealing with the mind, upon talking with Professor Yoro regarding human anatomy numerous times, his interest in the physical aspects deepened and he began to recognize that while the mind was important, so were the body and brain.

Kasai’s topic of research was schizophrenia, a mental disorder whose main symptoms are hallucinations and delusions, as well as declines in motivation, spontaneity, and cognitive function.

After graduating, Kasai served as a clinician at the University of Tokyo Hospital Department of Neuropsychiatry, but since he wanted to be in an environment in which he could study the physical aspects of the brain, he studied abroad at the Harvard Medical School Clinical Neuroscience Division. He continued with clinical research while serving as a visiting assistant. Kasai used MRI to carefully study changes in the shape of the brain over time soon after the onset of schizophrenia, which often occurs in adolescence, and he learned that the surface area of a specific part of the brain decreases by 7% after the onset of the disorder.

This was a groundbreaking finding that overturned the accepted view that, in the case of mental disorders, physical changes do not take place in the brain. This discovery has contributed to the current international view regarding schizophrenia, that if support can be provided early on, prognoses can be improved.

What is “true recovery” for patients who have mental disorders? There seems to be a gap between the image of recovery held by the persons involved and the general public, so providing a universal answer is difficult.

Kasai uses the expression “personal recovery,” which is advocated by Mike Slade of the United Kingdom and others. He comments, “If, in the patient’s own subjective view, he or she is able to live life sufficiently actively, to me this seems to be perfectly acceptable.” Thus, he is aiming to get his own patients to feel sufficiently happy in spite of having an illness and to have actually benefited by having grown as a person as a result of having an illness.

Doctors need to be ready to come to terms with the pain of the persons involved and become a part of their lives. Kasai states, “It seems that it’s the upbeat psychiatrists who end up not being very likable.” As for the ones that are likable, he says, “Those showing signs of hardship and who appear to be a bit tired. Some people say that it is as if patients want the doctor to suffer along with them.” In other words, Kasai says that the doctor’s own way of living is the message, and that this is a job that requires dedication on a day-to-day basis since it is necessary to naturally give patients the sense that “this doctor will understand my situation.”

Kasai points out, “Since I did not get off to a very good start in my own life, I believe that there are always ways to move one’s life in a positive direction.” Kasai says that he often reflects on when, in the midst of being shy and brooding as a child, he discovered his passion and pursued that path, and he believes that this is what led him to where he is today.

When Kasai is asked about his policy regarding research, he gives a simple answer: “consistency.”

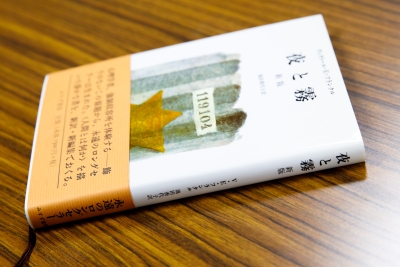

Man’s Search for Meaning (author: Viktor Frankl)

Viktor Frankl was a psychiatrist who miraculously survived being held prisoner in a concentration camp. His book, Man’s Search for Meaning, which shares his shocking experiences, has become an international bestseller. Kasai came across this book in his first year of high school, and it led him to aim to become a psychiatrist. He has since reread the book numerous times.

[Text: Hito wa dou ikite iru noka (“How do people live their lives?”)]

Rather than “how life should be lived,” Kasai is interested in “how life is being lived,” i.e., life processes. He comments, “Even if a patient wants to die, I have to bring about a situation in which that person stays alive. Unlike research, clinical work is not about fantasies.”

Profile

Kiyoto Kasai

Graduated from University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine in 1995. After serving as resident at University of Tokyo Hospital Department of Neuropsychiatry, resident at National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and Tokyo Musashino Hospital Department of Psychiatry, and doctor and assistant at University of Tokyo Hospital Department of Neuropsychiatry, went to the United States and served as visiting assistant at Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience Division in 2000, and then was reinstated as assistant at University of Tokyo Hospital Department of Neuropsychiatry in 2002. Has been serving as professor at University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine Department of Neuroscience since 2008. In area of mental disorders, achieves results in elucidation of brain pathologies, and focuses efforts on development of early intervention methods and early rehabilitation.

Interview date: February 13, 2019

Interview/text: Yukiko Kato. Photos: Takuma Imamura.