Towering figure of Western political thought inspires view of future|UTOKYO VOICES 079

Towering figure of Western political thought inspires view of future

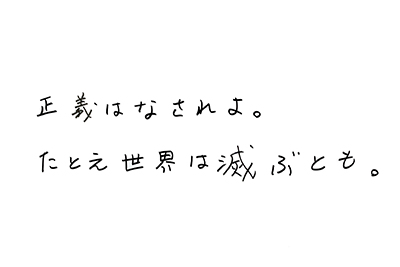

“Let justice be done, though the world perish.”

It may very well have been these words that Professor Yoshie Kawade encountered as an avid reader in her teens that steered her toward her current path: the history of Western political thought.

They are the words of a Holy Roman emperor who reigned during the 16th century, but the context in which he said them isn’t known for certain. All the same, those powerful words resounded with Kawade.

“The intensity of the words is the antithesis of Japanese calmness, which made me feel a disconnect,” she says. “But, despite that, I couldn’t simply disregard these words as being too extreme. They had a major impact on me; I found myself thinking what did he mean by ‘justice,’ and what does ‘the world’ refer to?”

Without finding exact answers to those questions, Kawade went to university, where she studied the history of political thought.

“I was just the sort who split hairs and liked to delve into questions like ‘What is the meaning of life?’, or ‘What is freedom?’” she says, looking anything but as she affably smiles from ear to ear and peppers her talk with high-pitched laughter.

Kawade’s studies focused on Montesquieu, a philosopher of the French Enlightenment who wrote the political treatise The Spirit of the Laws. But what’s the point of studying an 18th-century French political thinker in 21st-century Japan?

Even when this provocative question is thrown at her, Kawade answers cheerfully and without hesitation.

“It might sound paradoxical, but studying the history of political thought doesn’t just teach us about the past; it also gives us a perspective on the future,” she explains.

The history of political thought traces the origins of the principles and systems on which nations are built, sheds light on the political discourse of thinkers throughout the ages, and explains the successes and failures that nations have experienced. In doing so, it shows that modern society, which we tend to think of as an end point, is not absolute but relative to our circumstances.

For example, modern-day Japan is a democracy adopting the separation of executive, legislative and judicial powers advocated by Montesquieu. However, studying the history of political thought reveals that neither democracy nor the separation of powers is an absolute solution beyond question. Rather, they are no more than the current choices, arrived at after a long series of twists and turns in our political discourse.

Even in modern society, situations suggesting dysfunction in our democracy or the separation of powers frequently arise. Therefore, now more than ever, studying the history of political thought can play a critical role in shaping our political systems looking into the future.

“For example, by understanding what type of society Montesquieu lived in, what thoughts and experiences led him to advocate the separation of powers, and what division of powers existed in his time, we are able to explore a wider range of options for the future with greater flexibility,” Kawade says. “That’s why I see it as my job to describe the past in as much detail as possible.”

Unlike the natural sciences, there are very few dramatic breakthroughs that overturn existing views within the discipline of the history of political thought. Instead, you could say the field is built on adding to the body of findings that has accumulated until now.

“That’s why, no matter how small, I want to create and contribute something original that I can point to and say, ‘I provided this piece,’” Kawade explains.

Standing atop a high tower gives us a greater view of the future, and it’s the researchers all around the world and all through history who work to gather the bricks that enable us to build that tower taller and stronger. As one such researcher, Kawade searches among the stacks of the literature of old for materials that she can use to make more of these bricks.

Clock

“When I was a child, I got sick and it took me quite a long time to get better. Thankfully, when I was 18, my doctor carried out radical treatment to cure me and I was able to go to university. That doctor gave me this clock to congratulate me for getting into university.”

[Text: Seigi wa nasareyo. Tatoe sekai wa horobutomo. (“Let justice be done, though the world perish.”)]

“This isn’t so much a motto as words that have determined the direction of my life,” says Kawade. The phrase, originally in Latin, is attributed to Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I. Its impact on numerous thinkers, including German philosopher Immanuel Kant, has varied, resonating with some while others have reacted against it, and evoking many to add their own interpretations.

Profile

Yoshie Kawade

After graduating from the Waseda University School of Political Science and Economics, entered the University of Tokyo Graduate Schools for Law and Politics doctoral course. Following a period of study at Paris Diderot University, obtained her Ph.D. in 1994. Served as assistant professor at the Open University of Japan, and assistant professor and then professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University. Assumed her current post in 2005. Conducted research as a visiting scholar at Boston University and the University of Cambridge. Won the Shibusawa-Claudel Prize in 1997 for her book Aristocracy and Commerce, which reveals how Montesquieu focused on the political significance of the aristocracy even as its power waned due to the rise of commerce.

Interview date: October 24, 2019

Interview/text: Eri Eguchi. Photos: Takuma Imamura.