From China to Japan (and back), researcher follows path of traveling books |UTOKYO VOICES 082

From China to Japan (and back), researcher follows path of traveling books

Professor Jie Chen was an elementary school student in the early to mid-1970s during the latter stage of the Cultural Revolution that swept across China.

“Even as a child, I had a daily sense that great changes were happening in the world,” she says.

Sometimes her teachers would criticize the words of Confucius — even the regard for historical figures worthy to appear in children’s books changed like the wind, depending on the political climate of the day.

And this was the reason why Chen was attracted to ancient philology, to survey old written texts. When studying historical materials, she could make her own judgments after viewing the texts directly, rather than being told what to think based on someone else’s view of the world.

After going on to study at Peking University and embarking on research in Chinese classics, Chen came to Japan in 1994 — in search of historical Chinese texts that had been lost in China. As she conducted her investigation, she came across the records of Chinese people who arrived in Japan during the Meiji era (1868–1912) searching for historical Chinese texts.

“Because they couldn’t speak Japanese, they communicated with Japanese people through messages written in kanbun (Sino-Japanese writing),” says Chen, referring to the visitors from China more than a century ago. “When I read their written memos, letters, diaries and other materials, I could trace the paths that the ancient books took. But the details of the Chinese scholars’ search efforts and their communications with the Japanese had never been studied, so I decided to take up the research.”

This research — what you might call a “history of book traveling” — not only traces the route that the books traveled; it also sheds light on an array of stories and social conditions that lie behind them.

“During the early Meiji period, a large number of art objects and classical texts, including Chinese books, flowed out of Japan due to a shift in values and changing social climate, in which the country adopted Western culture and suppressed Buddhism. Many Chinese texts were sent abroad to China,” explains Chen.

Chen’s studies have shown that during this period, texts were not only moved by Chinese scholars, but also traveled through commercial channels.

However, in the late-Meiji and Taisho (1912–1926) eras, the zaibatsu conglomerates, which had risen to power in Japan, and newly established research institutes began collecting overseas works of art and culturally valuable texts, including those from China. Meanwhile, in China, a large amount of cultural property was moved overseas as the reign of the Qing dynasty was coming to an end. During that period, books traveled from China to Japan — that is, in the opposite direction as that of the early Meiji era.

“Now, with the expansion of the Chinese economy over the past 20 years, the flow of books is heading back in the direction of China. It is interesting to see history repeat itself, right before my eyes, by watching a replay of what I observed through my study of history,” remarks Chen.

Historical materials such as letters and other written communications offer a glimpse of the exchange that took place between Chinese people searching for Chinese texts and the Japanese who cooperated with them. They also reveal the clashes between people of different cultures, as well as the joys of unexpected episodes of mutual understanding. Chen explains that the history of book traveling is also a history of exchange across national borders, involving people from a wide variety of social backgrounds.

In recent years, although there has been a dramatic increase in the amount of contact between the Chinese and Japanese, it has not always led to fostering mutual understanding in all areas.

“The history of book traveling has taught me that time and experience are important to nurture mutual understanding,” says Chen. “Through repeated contact with people whose values differ from our own, we can put our own values into context. This, I believe, is the starting point for mutual understanding.”

While interpreting nameless historical materials, Chen sheds light on history from her own original perspective, discovering new meaning in what she uncovers.

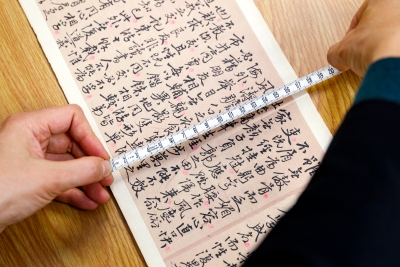

Text and tape measure

Pictured here is a letter that Chen found in Japan. Sent to a Japanese person from a Chinese person who came to Japan during the Meiji era, the letter contains an apology that suggests that the sender had caused a great deal of inconvenience to the recipient. A tape measure is an essential research tool, used to measure the size of such historical materials.

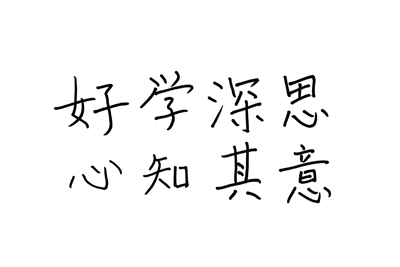

[Text: Hào xué shēn sī xīn zhī qí yì (“Pursuing and pondering deeply so as to give birth to ideas in one’s mind”)]

To understand the real meaning of texts, one must study and ponder them deeply. This maxim is from Historical Records: The Five Emperors, a history of China written over two millennia ago by the Chinese historian Sima Qian. “These words are a guiding philosophy for me, and I always tell them to my students,” says Chen.

Profile

Jie Chen

Came to Japan in 1994 after completing a master’s course in Chinese language and literature at Peking University and working there as a full-time lecturer. After conducting research at the Keio Institute of Oriental Classics and the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia at the University of Tokyo, enrolled in the doctoral course in the Division of Asian Studies, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology (Course of East Asian Thought and Culture) in 1995. Received a Ph.D. in 2001. Served as assistant professor in the Faculty of Integrated Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Humanities and Cultures at Japan Women’s University and professor in the Research Department of the National Institute of Japanese Literature, before assuming current position in 2017. Conducts research on the bibliographic culture of Japan and China and the history of Sino-Japanese academic exchange.

Interview date: November 18, 2019

Interview/text: Eri Eguchi. Photos: Takuma Imamura.