Inclusive sociological approach helps weigh impact of future medicine |UTOKYO VOICES 090

Inclusive sociological approach helps weigh impact of future medicine

This article is based on an interview with Professor Kaori Muto on Dec. 6, 2019.

Professor Kaori Muto speaks about her experience when she became sick and visited the hospital in the summer of her third year of university. Even after undergoing multiple exams, the medical staff still had not explained the results to her. Worried about her condition, when she asked the doctor what illness might be ailing her, he did not conceal his irritation at her behavior.

Muto says, “Back then, patients were expected to keep quiet and leave everything up to the doctor,” reflecting on the physician’s reaction.

The doctor barked out the name of the illness he suspected, a disease so often associated with a poor prognosis that Muto’s mother, sitting beside her daughter, broke into tears out of desperation.

Says Muto, “The diagnosis turned out to be incorrect, but the experience made me question why it was acceptable to not discuss the patient’s condition, which could turn out to be serious, with the patient or the patient’s family. That’s when I felt I wanted to properly study the relationship between medical staff and patients.”

After recovering from her illness, Muto went on to pursue research on medical ethics from the perspective of sociology, her original major. It was around that time that international guidelines for predictive genetic testing — that is, before individuals develop symptoms — of the hereditary disorder Huntington’s disease, were released. Muto, who was conducting research in the United Kingdom at the time, was deeply moved when she learned about the guidelines’ background.

In the discussions leading up to the guidelines’ adoption, experts and patient groups took part on an equal footing. Moreover, Muto says the discussions began when genetic testing was shown to be technically possible, that is, a long time before its practical application.

Back home in Japan, though, the groundwork for such discussions had not yet been laid, let alone discussions involving genetics were often deemed as taboo.

“I wanted to make it possible for these sorts of discussions to take place in Japan,” says Muto. “I wondered what I could do, and decided to pursue becoming a researcher.”

The social impact of emerging medical technologies — not just genetic testing, but also genome editing, regenerative medicine and other advances — raises a lot of issues to consider: Should parents be allowed to make decisions about altering the genes of their unborn child? Is it OK to create egg and sperm from iPS cells, stem cells that can develop into all types of cells in the body? And the list goes on.

What is called ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI) research, which began in the United States in the 1990s, takes an interdisciplinary approach at looking at these issues, and proposes proper applications and unsuitable uses of these emerging technologies in society. Muto serves as a leading figure of ELSI research in Japan.

Muto says she always makes a point of asking herself whether anyone has been left out of the discussion.

She says, “Opinions formed by perceptions that only people with the illness or disability realize are passed on to researchers, who in turn are frank when relating their conflicts and concerns. I feel it is important for advanced medical research to move forward with this kind of dialogue. I always try to make sure that nobody is left out of the conversation.”

The recommendations spawned by Muto’s research with her collaborators have gained a foothold in Japan. In addition to discussions on how society can embrace and apply emerging technologies, reflecting the opinions of patients to guide the future direction of research is finally starting to take hold.

Rather than relegating patients to the one-way street of passively receiving medical care, Muto aspires toward building a mutually respectful partnership between medical staff, researchers and patients. She is busy laying the groundwork for a society where tomorrow’s medical technologies can be discussed before they arrive, and the future shape of medicine can be explored through dialogue.

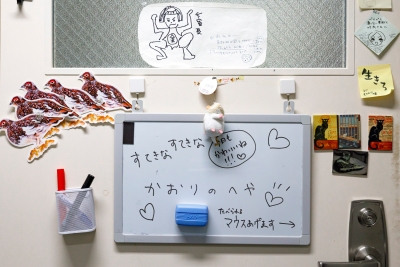

Lab door

The door to Muto’s office is decorated with messages from former colleagues and others. “I see these messages when I enter the room every day, motivating me to do my best,” she says. (A note at the bottom of the message board mentions “you will receive an edible mouse”; Muto points out laughingly that the mouse is not real, but a sweet snack.)

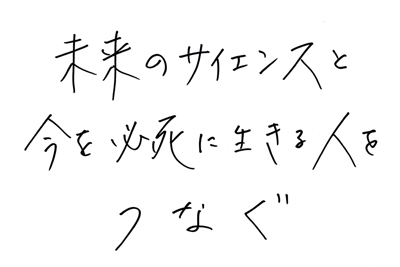

[Text: Mirai no saiensu to ima o hisshi ni ikiru hito o tsunagu (“Connecting the science of the future with people living desperately in the present)”)]

“Progress in medical research is made only with the cooperation of patients fighting illnesses today, but those patients themselves cannot be saved. A tremendous gap in timescale exists between researchers and patients,” says Muto. “I see the job of an ELSI researcher is to serve as a hinge that enables both groups to hold onto their dreams.”

Profile

Kaori Muto

After completing master’s program at the Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University, in 1995, enrolled in doctorate program at the School of International Health, Graduate School of Medicine at the University of Tokyo. Withdrew from program after completing course requirements in 1998, obtaining Ph.D. in 2002. After serving as lecturer at the School of Medicine, Shinshu University, became associate professor at the Department of Public Policy, Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science at the University of Tokyo. Has concurrently served as head of the institute’s Office of Research Ethics since 2009. Assumed current position in 2013. Specializes in medical sociology, and research and medical ethics. Worked to establish an advocacy group for patients of the genetic neurodegenerative disorder Huntington’s disease, and continues to support and record the group’s activities.

Interview date: December 6, 2019

Interview/text: Eri Eguchi. Photos: Takuma Imamura.