New picture of Islamic art emerges by questioning accepted views|UTOKYO VOICES 098

New picture of Islamic art emerges by questioning accepted views

While the Islamic world remains largely unfamiliar to people in Japan, Japanese art collections have housed Islamic artworks since the latter part of the 19th century, during the Meiji period. Today, Japan is home to the largest collection of Islamic art in East Asia, a fact unknown to many people.

Professor Tomoko Masuya is among the few researchers who study Islamic art in Japan. Her research focuses on the interaction between Eastern and Western cultures in Iran during the 13th and 14th centuries, a time when the Mongol Empire was flourishing.

Masuya has been interested in foreign cultures and history since a young age, perhaps due to being born and raised in the international port town of Nagasaki in southwestern Japan. When she read the Mother Goose collection of British nursery rhymes while still in elementary school, she became enthralled with the stories. “When I was a high school student, I decided that I wanted to study under University of Tokyo Professor Keiichi Hirano, an expert on Mother Goose,” she says.

Upon entering the University of Tokyo, Masuya had the good fortune of being able to join a specialized seminar run by Hirano. Unfortunately, she never got another chance to study under him, as Hirano was heading into retirement. So instead, she turned her focus to art history — a move that can be attributed in part to her grandfather’s uncle, Morinosuke Yamamoto, being a renowned artist from Nagasaki, and Masuya thereby being surrounded by paintings since she was a child.

An encounter with Islamic paintings in her third year as an undergraduate would have a profound impact on Masuya. “I first discovered Islamic art during a lecture on Persian Sufi literature, and I was drawn by its vivid paintings,” she recalls.

Setting off on the research path, Masuya went abroad, enrolling in the master’s program at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, where she later got her doctorate. She then became a research fellow at Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology before joining the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia at the University of Tokyo. Masuya describes herself as cautious to a fault, taking a slow and steady approach to interpreting art history that has resulted in her scholarly achievements.

Take for example her study of the Takht-i Sulaiman, a temple constructed in Iran in the latter half of the 13th century by the Mongols. Some of the temple’s tiles depicted drawings of Chinese-style dragons and phoenixes, while others featured quotations from Persian epic poems. Masuya studied the significance of this duality coexisting in the tiles’ motifs, and figured out they portrayed symbols of sovereignty as seen from the Mongol rulers’ viewpoint and that of the Iranian craftsmen who created the tiles. This revelation was the result of her becoming familiar with both Eastern and Western cultures, and taking a meticulous approach to studying her subject.

American and European researchers had long believed that 13th-century Islamic manuscript paintings were strongly influenced by Chinese paintings; however, the exact degree of this influence was unclear. So Masuya analyzed the section on early Chinese history in the Jami'al-tavarikh (Compendium of Chronicles), an illustrated history text, and found that the Chinese paintings depicted in there were rendered in a different style from Chinese paintings of that period, and that the clothing of the people featured in the text was portrayed inaccurately. Despite the focus on China, Masuya discovered that the portrayal of Chinese culture and the painting techniques featured in the text strayed from what actually existed in China. Masuya presented these findings in her 2014 book Isuramu no Shahon Kaiga (Islamic Manuscript Paintings) and provided further details in an English-language study of the topic in 2018.

“When people think about cultural exchange between East and West, many assume the relationship is between East Asia and Europe and they tend to overlook the Islamic region in between that had dealings with both cultures. I feel that studying the region’s art history allows me to talk about the aspect of cultural exchange more eloquently,” Masuya says. “As a researcher who was raised in Japan, I hope to provide insights from an East Asian perspective into research on Islamic art history.”

Masuya’s research covers a broad range of regions, periods, art and crafts, and her journey through the vast Islamic world continues.

“My next goal is to create a catalog of pottery shards collected from Egypt and now housed in the Ohara Museum of Art (in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture),” Masuya says. “I also hope to broaden my research to include illustrated manuscripts from periods and regions that I have not been able to cover to date, as well as the illustrations in a certain history text written in the early 14th century.”

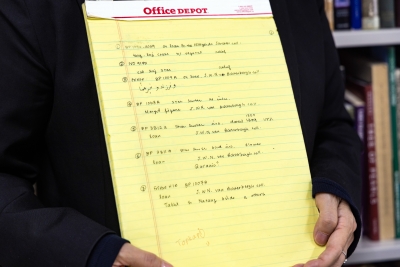

Canary yellow notebook

Since studying abroad, at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, Masuya has always carried around a canary yellow notebook with individually perforated pages that can be torn out. She jots down any random thought that comes to mind, and later tears out the pages that might be useful when writing her papers.

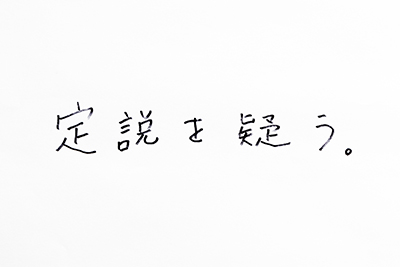

[Text: Teisetsu wo utagau “Question established theory”]

Instead of blindly accepting a set idea, Masuya believes that it is important to carefully review all its aspects. “Even experts can be wrong, so it is important to rid yourself of preconceptions, view previous research with a critical eye, and go back and rethink ideas,” she says.

Profile

Tomoko Masuya

Graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1986, received a doctorate from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University in 1997 and became research fellow at Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology the same year. Was appointed associate professor of the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, the University of Tokyo, in 1999, then professor in 2007. Served as director of the institute from 2017 to 2020. Published books include: Persian Tiles with Stefano Carboni, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Sugu Wakaru Isuramu no Bijutsu (Handy Manual of Islamic Art), Tokyo Bijutsu; Isuramu no Shahon Kaiga (Islamic Manuscript Paintings), University of Nagoya Press; and as editor: Zusetsu Isuramu Teien (Islamic Gardens and Landscapes, Japanese edition) by D. Fairchild Ruggles, Hara Shobo, and Isuramu Garasu (Islamic Glass) by Yoko Shindo, University of Nagoya Press.

Interview date: November 16, 2020

Interview/text: Tsutomu Sahara. Photos: Takuma Imamura.