Russian nationalism and the Russo-Ukrainian war

What kind of nationalist thought drove the Putin administration to invade Ukraine? Professor Kyohei Norimatsu (College of Arts and Sciences), a specialist in modern Russian literature and thought, explains some of the ideological underpinnings of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

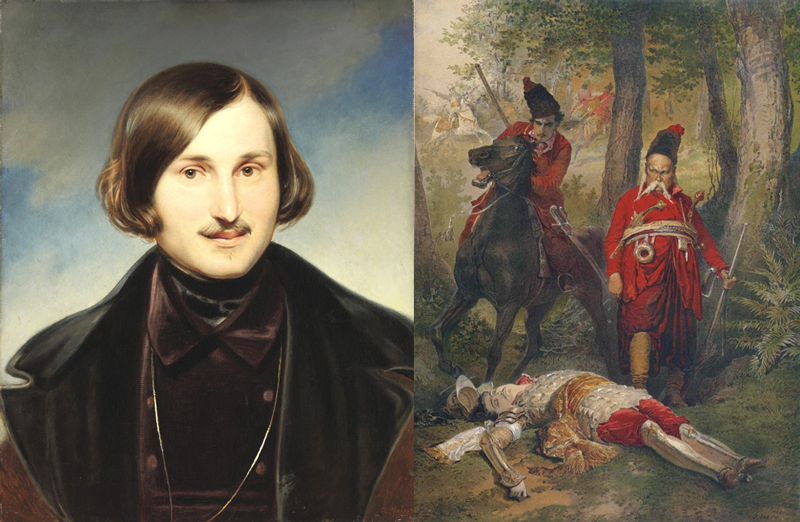

Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks by Ilya Repin, 1880-1891. ©Ilya Repin

Competing nationalisms and the Putin administration

―― What is your perspective on the current war?

Originally, President Putin was generally assessed as a level-headed politician who acted pragmatically based on realistic judgments, but in light of the events that have occurred since the crisis in Ukraine in 2014, that is an assessment that must be reconsidered. Russian nationalist thought has been noted as a factor in Putin’s change.

At the end of his September 30th speech in which he declared the annexation of four Ukrainian provinces, Putin quoted the words of exiled Russian thinker Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954). Ilyin was an individual who left behind writings on his homeland after his exile to Western Europe following the Russian Revolution, a trauma that he grappled with for his remaining life. In his especially famous work Our Tasks, which is a collection of post-World War II political commentaries, he warned that Russia could be divided up into disparate pieces by surrounding countries. It is likely that Putin shares this trauma-like sense of danger towards the idea of Russia no longer being a unified “whole.” However, that is an anachronistic view that also treats Ukraine, a sovereign state, as if it were a part of that whole.

What exactly does it mean to be “whole” or “unified” in the Russian context? Russia is a multi-ethnic nation of more than one hundred ethnic groups and an empire that maintains hold over its colonies. In order to depict such a medley of different groups as a single, unified nation, Russian nationalist thought has advanced the concept of “unity in diversity.” The current war can be traced back as an extension of that concept.

―― What does “unity in diversity” mean?

Russian nationalist thought came about as a result of Russia’s fixation on its own lack of uniqueness compared to countries in Western Europe. The search for that uniqueness began with the rise of modern nationalism at the beginning of the 19th century. At that time, intellectuals and aristocrats were highly culturally dependent on the West and viewed Russian uniqueness with pessimism. For example, writers and literary critics in the 1820s and 30s often complained that all Russian literature was Western facsimile, and so could not be called uniquely Russian. In the 1840s, however, a paradoxical discourse emerged in which the lack of uniqueness was, in and of itself, unique. Vissarion Belinksy (1811-1848), one of the leading literary critics of the time, stated that when a Russian goes to Britain, he becomes like the British, and when a Russian goes to France, he becomes like the French, and that this high degree of adaptability is specifically unique to the Russian people.

It is important to note that Belinsky references a literary work set in the Caucasus, which was under invasion by the Russian empire at the time, as supporting evidence for this adaptability. In that work, there is a Russian character who went to serve at the front in the Caucasus, set down roots, and became a local; in other words, he adapted to the Caucasus. In that way, in order to reinterpret the negative “lack of uniqueness” as the more positive “high adaptability,” it was necessary for Russia to compensate for the fixation on Western Europe with a sense of superiority over the colonies. Imitating the West was embarrassing, but it fostered an ability to imitate that turned into a point of pride when integrating colonies. Russians are indistinct, empty vessels, and it is precisely for this reason that Russia is able to encompass a variety of other peoples, or so the assertion goes.

On the other hand, people known as Slavophiles discovered Russian uniqueness in the representation of unity found in religious philosophy. The thinker Aleksey Khomyakov (1804-1860) said that Christians who pray in church become one with Christ, and that all churches together form an organic cohesion as one. He claimed that in comparison with Western Catholicism and Protestantism, it is only in the Eastern Orthodox church that a sense of unity based on the freedom of each believer, or “unity in diversity,” is realized. This concept of unity was applied not only to the Church, but also to the Russian state and its people.

This is how the idea developed that Russia’s national identity is its ability to embrace diversity, and that the more it annexes various ethnic groups, the more “Russian” it would become. This idea also functioned as a device to resolve the contradiction in Russian nationalism that Russia is both a multi-ethnic empire and a nation-state exclusively for the Russian people. Having struggled with its lack of an ethnic, national identity, Russian nationalism compensated for this lack by creating a national identity based in imperialism. During the Soviet era, communist ideology became the mainstay for preserving the multi-ethnic nation’s unity, but with the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, imperial nationalism underwent a revival.

―― How has the ideology of the Putin administration changed since the crisis in Ukraine in 2014?

The default stance of the Putin administration is imperial nationalism, but Russian ethnic nationalists have long criticized that stance, and the way this relationship changes is important to note. Russian ethnic nationalists advocated for a Russia for the Russian people, and they problematized the contradiction I mentioned earlier between Russia as a multi-ethnic empire and Russia as a nation-state. Through exclusionary movements targeting immigrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus, Russian ethnic nationalism gained strength as an anti-establishment force.

However, after the crisis in Ukraine in 2014, most Russian ethnic nationalists turned away from anti-establishment rhetoric, and their arguments shifted to support Russian expansion rather than the elimination of other domestic ethnic groups. The idea of rescuing “persecuted” Russians living in former Soviet regions strongly appealed to Russian ethnic nationalists, so they were fervent supporters of the separatist uprising in Donbas and Russia’s annexation of Crimea. They also insisted on active military involvement in Ukraine and applied pressure early to mobilize in the current war. As a result, the Putin administration gives the appearance of being dragged along by the ethnic nationalists it has incorporated into its support base.

Eurasianism and a repeated fixation on the West

―― Eurasianism has drawn attention as the ideological background of the Putin administration’s imperial nationalism.

The concept of “Eurasianism” was first formulated in the 1920s by exiled intellectuals who asserted that there existed an organic unity in the region of Eurasia, which is cut off from the West. Linguists Nikolai Trubetzkoy (1890-1938) and Roman Jakobson (1896-1982), for example, proposed the idea of a “Eurasian Sprachbund,” arguing that the languages of Eurasia constitute of a single grouping.

From a “language family” perspective, which has been dominant since the 19th century, languages that have a common origin gradually branch into different languages. However, it would be illogical to seek commonalities between languages with different origins, like Russian and Tatar. In contrast, a “sprachbund” is formed when languages with disparate origins gradually develop commonalities with one another through interaction due to geographic proximity. From this perspective, it also becomes possible to claim that even if two things were not part of the same unified whole initially, a sense of unity can be created over the course of history. Such an approach to unity is incredibly imperialistic.

The Eurasianist movement was forgotten during the Soviet era, but as ethnic awareness grew and the unifying power of communism weakened, it was rediscovered and “New Eurasianism” was proposed. Setting aside the direct impact of this concept on the Putin administration, the means by which a region with no sense of unity can develop one is an ideological problem common to both Eurasianism and the Putin administration.

However, as I mentioned earlier, what I feel is important in the events leading up to the invasion of Ukraine is the fact that the imperial nationalism of the Putin Regime was eroded by Russian ethnic nationalism. Part of ethnic nationalism is the idea that unity is innate. By approaching unity between Russia and Ukraine not as something that emerged over the course of history, but as something that has existed all along, the desire to “restore” that sense of unity has grown stronger.

―― Where is the line between the “self” and “other” in Russian nationalism?

Russia shares a land border with the regions into which it expands, and it has forged and broken alliances with these regions repeatedly over the course of history. As a result, Russia has an environment in which it is easy to justify a sense of unity with annexed colonies as “natural.” Though Russia made a distinction between “self” and “other” in its relationship with the Western Europe, it blurs that boundary when it comes to its contiguous colonies, instead opting to incorporate them into itself. Russia’s relationship with Ukraine is also characterized by a similar ambivalence that makes it difficult to classify Ukraine as “self” or “other,” from Russia’s perspective.

For example, Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852), a prominent figure in Russian literature known for his portrayals of Ukraine, depicts a battle between Poland and the Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia (present-day southern Ukraine) in his historical novel Taras Bulba, which is set during the period when Ukraine was under Polish influence.

The novel was first published in 1835 and revised in 1842, and the revised version had various rewrites that changed the Cossacks, who were originally described as inhabitants of “Little Russia” (i.e., Ukraine) into symbol representations of Russian ethnic identity. The Cossacks were a group of people with various ethnic backgrounds who, beginning around the 15th century, formed armed bands on the periphery of Russia. Although they would pillage the surrounding areas, they also entered into an arrangement with the Russian government to guard the borders. Thus, the Cossacks were a group whose association with Russia was ambiguous, but it is precisely because of that ambiguity that they were able to symbolize Russia’s “unity in diversity.”

―― Is it possible to bridge the division between Russia and the West?

Overcoming their fixation on Western Europe has been a difficult challenge for Russia. The trauma caused by Russia’s struggle with its lack of uniqueness compared to the West has been repeated throughout history. The communist movement, which rejected Western modernity and capitalism and sought to establish a new universal norm, initially attempted to overcome the division with the West, but as a result, it became trapped in a confrontational relationship with the United States and Western Europe in the form of the Cold War. The same pattern, wherein Russia either idolizes the West or rebels against it to return to ethnic traditions and religions, has existed since the 19th century. It was eventually repeated during the Soviet era as well, and it ultimately became a factor in the collapse of the Soviet Union.

To this day, both the new universal norm of communism and rebellion in favor of ethnic particularities exhibit the same tendency to fall back on a fixation on the West. That said, this is not solely a Russian problem. Outside the United States and Western Europe, and even within them, there are growing movements away from modern universals in favor of a return to ethnic traditions. We must be careful not to think about what is happening in Ukraine and Russia as something happening only to someone else.

Kyohei Norimatsu

Professor, College of Arts and Sciences

Ph.D. (Letters) from the Division of European and American Studies, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, the University of Tokyo. Publications include Roshia aruiwa tairitsu no bōrei: “Dai ni sekai” no posutomodan (“Russia or the Specters of Opposition: Postmodernity in the “Second World””) (Kodansha, 2015), Riarizumu no jōken: Roshia kindai bungaku no seiritsu to shokuminchi hyōshō (“Conditions for Realism: Colonial Representations and the Formation of Modern Russian Literature”) (Suiseisha, 2009).

Interview: October 26th, 2022.