Cultivating pearls and community ties Researchers explore, expand on UTokyo’s century-old connection to popular gem

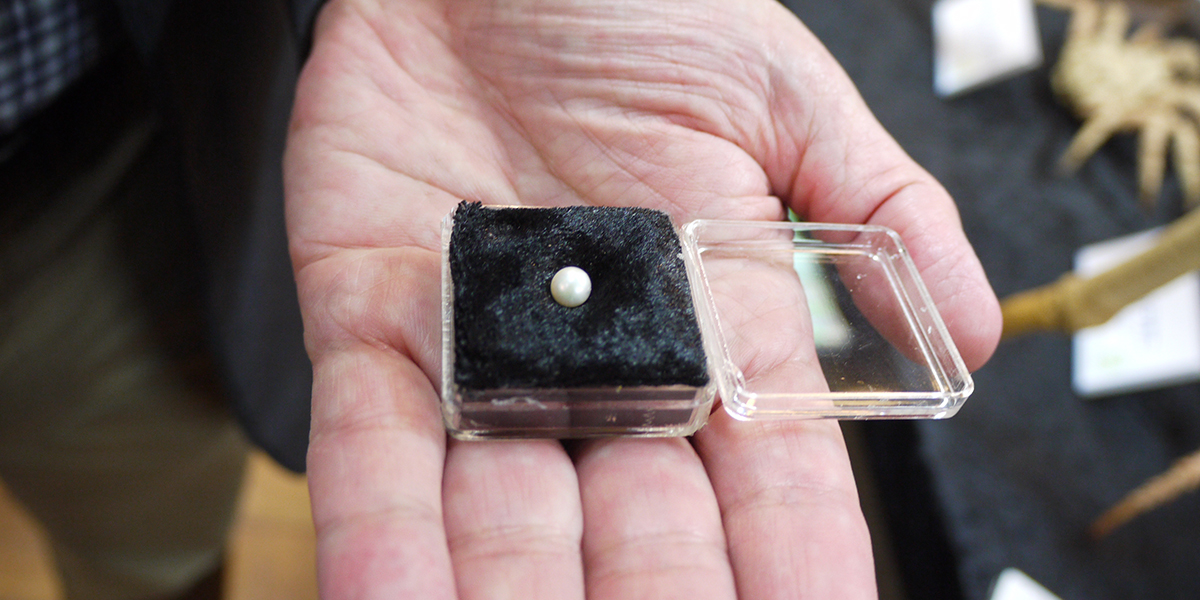

One of a few dozen pearls harvested in 2016 in the city of Miura, Kanagawa Prefecture, as part of the Miura Pearl Project, is shown here. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

They’ve adorned Audrey Hepburn, Princess Diana and Michelle Obama. Many of us who are neither royal nor famous have worn them, too, on one occasion or another.

Pearls, with their round shape and iridescent luster, have long been a popular and familiar jewelry choice for people around the world.

What many people may not know, though, is the not-so-insignificant role the University of Tokyo has played in making the gems widely accessible, by helping with the invention of techniques to cultivate pearls — a role that laid the foundation for today’s pearl farming industry.

In fact, the Graduate School of Science’s Misaki Marine Biological Station (MMBS) is credited with inspiring a man from Mie Prefecture, in central Japan, to create the world’s first cultured pearls and commercialize them. The station, set up in 1886 in the city of Miura just south of Tokyo in Kanagawa Prefecture, is one of the oldest marine biology research facilities in the world.

MMBS’ contribution to pearl culturing from over a century ago is back in the spotlight as its recent efforts to revive the local pearl farming industry and teach marine ecology to students through the Miura Pearl Project have gathered momentum.

The researchers, who are only months away from harvesting pearls from pearl oysters being farmed at the facility, are also hoping to boost cross-disciplinary research on biomineralization, the process by which living organisms including oysters produce minerals to harden their tissues.

Ties with Mikimoto

Professor Kakichi Mitsukuri © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

MMBS’ connection with pearls dates back to an encounter in 1890 between Kakichi Mitsukuri, its first director, and Kokichi Mikimoto, a merchant from Shima, Mie Prefecture, who dreamed of producing gem-quality pearls.

Back then, only natural pearls — created by oysters as they tried to defend themselves from foreign intruders — were available. Natural pearls are made when mother-of-pearl, or nacre, which is composed of calcium carbonate and protein, is secreted from the mantle tissue of the oyster and wraps the foreign objects around it. Produced by chance, natural pearls were highly prized and overharvested, driving pearl oysters in Japan to the point of near extinction by the late 1800s.

Mitsukuri, who saw the oysters showcased by Mikimoto at an exposition in Tokyo in 1890, told him that it is theoretically possible to culture pearls. According to a 2013 paper authored by Kiyohito Nagai, a fishery researcher and director of the Mikimoto Pearl Research Laboratory, Mikimoto later visited MMBS, where he received a weeklong comprehensive lecture from Mitsukuri — covering everything from the theory of pearl formation to the state of pearl research in Europe to examples of earlier attempts at pearl culturing from around the world.

Mitsukuri, in his English-language paper submitted to the Bulletin of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries in 1904, also wrote that he encouraged Mikimoto to try culturing pearls.

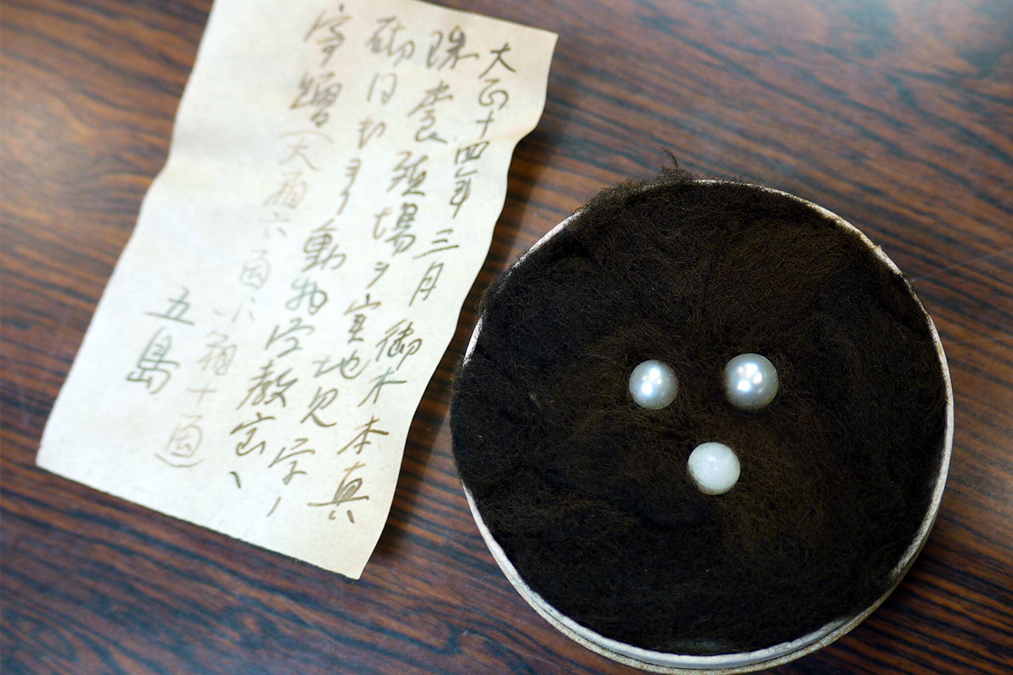

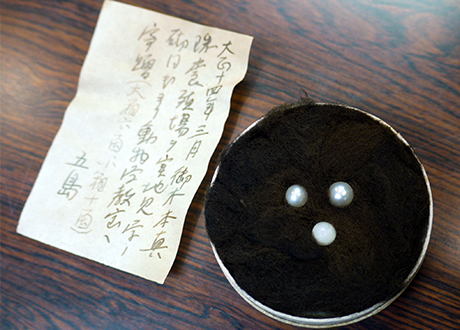

Cultured pearls donated to the university in 1925 by their creator, Kokichi Mikimoto, founder of present-day K. Mikimoto & Co., are seen here alongside a handwritten memo left by UTokyo zoologist Seitaro Goto. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

“In 1890 I suggested to a Mr. Mikimoto, a native of Shima … the desirability of cultivating the pearl oyster,” Mitsukuri wrote. “He took up the subject eagerly and began making experiments on it. Soon after I pointed out to him also the possibility of making the pearl oyster produce pearls by giving artificial stimuli. He at once proceeded to experiment on it.” Mikimoto toiled away at finding the best kind of foreign object to put in and where to insert it, eventually succeeding in creating hemispherical pearls.

Meanwhile at the university, researcher Tokichi Nishikawa carried out pearl studies under Mitsukuri’s tutelage. Nishikawa divided his time between MMBS and the Mikimoto Pearl Research Laboratory, and established a method to create spherical pearls by grafting a piece of the mantle from a donor oyster and inserting it into the recipient oyster, thereby inducing the formation of pearl sacs. Nishikawa later acquired patents for his techniques, according to Nagai’s paper.

In 1908, the university adopted pearl culturing as a formal research project, hiring Nishikawa and two other researchers. But the university shut down the program in 1912, following the deaths of Nishikawa and Mitsukuri in 1909.

Mikimoto, on the other hand, continued research and production of pearls, turning his company — nowadays called K. Mikimoto & Co. — into the global jewelry brand it is today.

Rediscovering history

The Koajiro Bay in southeastern Kanagawa Prefecture, where the Misaki Marine Biological Station is situated, is blessed with marine biodiversity that makes the location ideal for research. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

Until recently, UTokyo’s historical ties to pearl farming “had been almost forgotten, even by the university,” says Yoshitaka Oka, a professor of zoology at the Graduate School of Science who also serves as MMBS’ current director. Oka himself discovered this part of history by chance.

In 2003, when he returned from his eight-year stint at MMBS to the Graduate School of Science as a professor on the university’s Hongo Campus, he discovered some old cylindrical boxes kept in his office. Inside them were pearls donated to the university by Mikimoto in 1925, with a yellowed handwritten note by Professor Seitaro Goto, then-head of the school’s zoology department.

“The boxes had been casually left in a corner of the office like nothing special,” Oka recalled. “But since I had heard about the story of pearls in my days as a UTokyo student, I immediately realized that they were items of historical significance.”

Professor Emeritus Koji Akasaka, who served as MMBS director from 2004 till 2017, says he himself didn’t know about UTokyo’s connection with Mikimoto until about a decade ago, when officials of K. Mikimoto & Co. approached him and asked the university to co-host a symposium on pearl culturing and marine environment to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the birth of Kokichi Mikimoto in 2008.

The symposium, held at Koshiba Hall on the Hongo Campus, has helped rekindle UTokyo-Mikimoto ties. It has also inspired Akasaka to use the legacy as part of UTokyo’s efforts to interact with local communities and promote ocean environment education.

Professor Emeritus Koji Akasaka © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

Since 2013, Akasaka, who is now a project researcher at the university, has spearheaded the Miura Pearl Project in cooperation with the city of Miura and the Mikimoto company. The aim is to revive a pearl industry in the city, which hosted a small farming operation briefly after World War II, and teach marine diversity to local schoolchildren.

Akasaka says he also wants to help nurture the next generation of pearl farmers. “The industry needs young blood as workers are aging and their ranks are dwindling across Japan,” he said.

Following a harvest of a few dozen pearls in 2016, in which local elementary school students participated, MMBS has stepped up production of pearls at its own site, fertilizing oyster eggs and growing oysters in nets hung in the ocean off its pier facing Tokyo Bay. In late July, MMBS staff inserted two nuclei into each of about 100 oyster shells — a crucial stage in pearl farming, which requires intricate handwork with surgical tools and tiny nuclei, which are made from Mississippi River mussel shells.

A teacher from the Kanagawa Prefectural Marine Science High School practices inserting mantle pieces and pearl nuclei into a pearl oyster at the Misaki Marine Biological Station in late July. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

“Basically it’s surgery, so it’s extremely important to prepare the oysters beforehand,” Akasaka explained. “You have to make the baby oysters somewhat starved over the preceding winter, by placing them tightly together in nets, thus keeping their ovaries from overgrowing. If their ovaries grow too big, there won’t be room to put in the nuclei. You also have to make sure they won’t move around too much soon after the surgery, because if they do, they could spit the nuclei out.”

On the same July day, three teachers from the Kanagawa Prefectural Marine Science High School in the city of Yokosuka practiced grafting procedures at MMBS. The teachers plan to impart these skills to their students in the hopes that the students would become interested in pearl farming as a career choice. The teachers have also visited the Mikimoto research facility in Toba, Mie Prefecture, to learn the techniques, and students from the school have visited MMBS to clean the shells of the oysters, which become covered with all kinds of tunicates and mussels.

“Our hope is for our students to be skilled enough to handle the nuclei themselves in the future,” said Yasuo Sonohara, a teacher in charge of regional cooperation at the high school. “But first we need to master the technique ourselves so we can keep the oysters from dying.”

Science of pearl formation

MMBS director Oka says he wants the pearl project to be a springboard from which the university’s researchers advance the study of biomineralization, a process by which all kinds of living organisms, including oysters, produce minerals to harden their tissues.

The main building of the Misaki Marine Biological Station in the city of Miura, Kanagawa Prefecture, is seen here. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

Kazuyoshi Endo, professor of earth and planetary science at the Graduate School of Science, was one of the researchers involved in decoding the pearl oyster genome for the first time in 2012. The research team also included scientists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and Mikimoto.

“Many experts believe there are genes that control the colors and growth of pearls, as well as the health of pearl oysters,” he said. “Oysters are prone to infection by viruses and contamination by pathogenic bacteria, so research is currently underway (at other institutions) to determine what types of genes are related to such characteristics. Genome decoding has opened doors to the potential of greatly advancing pearl science.”

Endo is a paleontologist who’s interested in pearl oysters and other mollusks as part of his study on the evolution of creatures and their acquisition of abilities to create hard tissues such as bones and teeth. He says there’s a lot of scientific insight to be gained from the study of biomineralization.

“Mother-of-pearl is known to be extremely hard and strong,” he said. “It’s made of calcium carbonate and proteins. Though calcium carbonate itself is fragile, it becomes superhard when it is mixed with a small amount of proteins. Such characteristics could potentially be used in the field of engineering, for example, to create new industrial materials.”

Back at MMBS, Akasaka is eagerly waiting for a harvest. If things go well, the researchers will get as many as 100 pearls early next year, he said.

“We have reached a stage where we can produce pearls ourselves,” Akasaka said. “We look forward to showing our pearls in January, and showing a lot more — as many as 1,000 pearls per year — in the coming years.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake