Turning aging society on its head Web app helps seniors find jobs, stay connected

Members of Chiba-based group SLF Garden Support practice pruning in the garden of a private home in the city of Kashiwa in late July. Most of them are retired white-collar workers with no prior gardening experience. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

In Japan’s superaged society, where one out of four people is over 65 years old, public debate often focuses on spiraling social security costs to support the elderly and how to keep the country from buckling under the huge financial burden.

Dr. Atsushi Hiyama, a lecturer at the University of Tokyo’s Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, however, envisions a completely different scenario for Japan’s future, where seniors utilize their potential to the full to support the young.

University of Tokyo Lecturer Atsushi Hiyama © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

GBER, short for Gathering Brisk Elderly in the Region, is a web app developed by Hiyama to help realize such a society, by matching jobs with the interests of healthy and active seniors, and helping them share tasks with others.

The app’s name is a pun on the popular ride-sharing service Uber. It is also derived in part from the Japanese moniker for elderly men (jiji) and elderly women (baba), Hiyama explained.

GBER has become an indispensable tool for a senior citizens group in the city of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture, to manage tree-pruning jobs it undertakes from residents and institutions in the area.

“I’ve met many retired people and I have been amazed by their vitality,” Hiyama said in a recent interview. “They want to work, but they don’t necessarily want to put in long hours like they used to. Many of them don’t want to commute to the same place every day, either. They regard work after retirement as a means to maintain their health, make friends and try new things. They want to work because they want to stay connected with society.”

Turning a population pyramid upside down

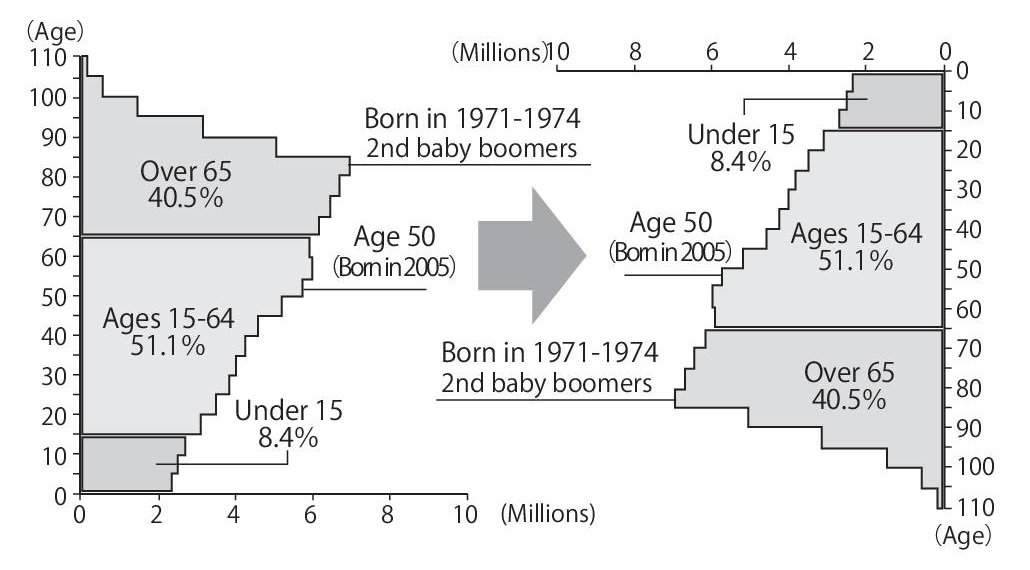

Hiyama points to two renderings of Japan’s population pyramid in 2055. The left chart shows how thin layers of young people need to support the bulky senior ranks above them. The chart on the right uses the same population statistics but has the ages turned upside down, with older people shown at the bottom of the pyramid. © 2018 Atsushi Hiyama.

Hiyama says he is confident that technologies can offer solutions for such needs and address the nation’s demographic challenges at the same time. To make his point, the researcher points to two renderings of population pyramids – one that is typically used to illustrate the projected demographics of Japan in 2055, where ages are listed in ascending fashion from zero to 110 and shows how thin layers of young people need to support the bulky senior ranks above them in a tipsy inverted pyramid. He then points to another chart that uses the same population statistics but has the ages turned upside down, with older people shown at the bottom of the pyramid. In the second chart, looking a lot like Japan’s demographics from the past, a solid base comprising large groups of baby boomers (born in 1971-1974) and those older at the bottom support the young people above. This second scenario epitomizes the future Hiyama envisions.

GBER is part of a new concept he calls “mosaic employment,” through which a number of seniors combine their resources and collectively perform the tasks traditionally undertaken by a single full-time employee.

To develop a crowdsourcing app that fits the characteristics of the elderly workforce, Hiyama has worked closely with a community of seniors in Kashiwa, aiming to provide a one-stop solution for handling community-based projects involving a large group of people.

In late July, around 20 members of SLF Garden Support gathered in the front yard of a private home in Kashiwa to practice their pruning skills. The civic group – an offshoot of a larger community group, Second Life Factory, which was launched in 2013 by participants of employment seminars hosted by UTokyo’s Institute of Gerontology – comprises mostly retired white-collar workers with no previous pruning or gardening experience.

SLF Garden Support, set up in 2015, organizes a series of lectures and practice sessions on pruning for seniors interested in picking up the skills. About 100 people so far have completed the training program taught by professional gardeners, SLF Garden Support leader Akihiko Bando said.

‘Part work, part fun and hobby’

Members of SLF Garden Support learn pruning skills from a teacher at a private home in the city of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture, in late July. An app developed by UTokyo Lecturer Atsushi Hiyama has become an indispensable tool for the group to undertake pruning jobs and organize members’ schedules. © 2018 The University of Tokyo.

“It’s part work, part fun and hobby,” the 72-year-old former banker said about participating in the group. “We enjoy going out for drinks after we get our work done. If we don’t have fun, a project like this won’t last long.”

GBER has been useful for the group to recruit people for projects that involve as many as 30 people, he said. Compared with other scheduling apps, GBER is convenient as it has a calendar that shows at a glance who and how many people are available to carry out tasks on particular dates over the next two months, according to which the group’s managers can schedule pruning contracts, he said.

Elderly people with entry- or midlevel job skills have traditionally registered themselves at “Silver Human Resources Centers,” publicly funded, municipally run job agencies for seniors. Such centers, whose primary goal is to give seniors “a motivation in life” and a means to help revitalize their communities, handle requests from citizens for various one-off jobs at a reasonable cost. The jobs undertaken vary widely and include pruning, carpentering, tutoring of school subjects and housecleaning, but because they are only restricted to “easy, light work,” many seniors are not happy with the arrangement and have stayed away from registering.

The same goes for pruning, where these public job centers don’t allow certain heavy equipment to be used and limit the height of trees to be pruned, Bando said.

“While workers dispatched by Silver Human Resources Centers work alone, we undertake a project as a group and divide up the work among 30 people, for example,” he said. “That way, we can complete the project in three hours, instead of several days. We are not professionals, but try to provide the level of service higher than those provided by silver centers.”

GBER has also been used by other groups in the Kashiwa area, which provide short-time work as assistants for nursery teachers and farmers.

GBER is a crowdsourcing app for a group of people to undertake projects such as tree pruning. It is equipped with a calendar, a map and a questionnaire to find out what jobs and activities are available that fit users’ interests. © 2018 Atsushi Hiyama (left). © 2018 The University of Tokyo (right).

Now that the 2-year-old app has led to more than 2,300 job placements in the Kashiwa area, Hiyama wants to expand the app’s functions by accumulating data, so in the future it can make personalized job recommendations to people according to their preferences and past experiences, he said. Hiyama also wants to take the app’s success beyond Kashiwa. He is currently in talks with prefectural governments of Kumamoto and Yamanashi to use GBER in their communities, he said.

The job market for the elderly has huge room for improvement, Hiyama said, noting that there are millions of active, healthy seniors who are retired from white-collar jobs and whose talents have not been put to use. This is because currently there are only job-matching services for contract work for superskilled, top-level executives or low-skilled work referred by public job placement agencies.

“If we could create a system for these energetic seniors to be active and help young people, our population pyramid would look a lot different – and become a far more stable one.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake