To the front lines of public health UTokyo experts assist public health centers and hospitals with COVID-19 response

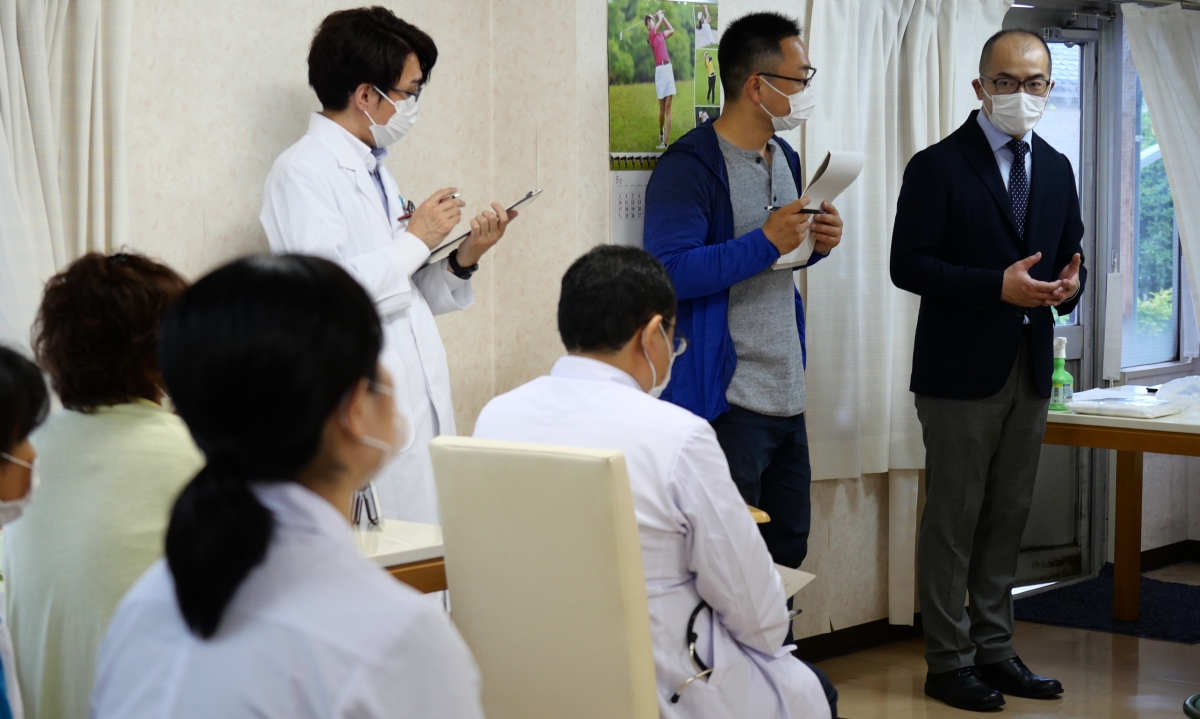

UTokyo lecturer Dr. Jun Tomio (left) and Ashikaga University nursing expert Hiroyuki Murakami (center) explain how to remove personal protective equipment safely at Suginami Hospital in Tokyo on May 19, 2020.

On May 19, 2020, Dr. Jun Tomio faced a crowd of about 20 people, mostly doctors and nurses, in a conference room at Suginami Hospital in Tokyo’s residential Suginami ward.

Tomio, a lecturer at the University of Tokyo’s Department of Public Health, asked one of the nurses to step forward and try putting on numerous equipment laid across a table: a plastic gown, gloves, goggles, a face shield, a cap, an N95 mask and white protective clothing known as Tyvek.

“You might have imagined wearing this white coverall clothing,” Tomio told the attendees as the nurse put on one gear after another. “But what you basically need is a pair of gloves, a mask, a face shield and a long-sleeved plastic gown. Please make sure to put these on and take them off correctly.”

Hospital staff listened attentively and took notes as Tomio and Hiroyuki Murakami, an expert on infection control nursing at Ashikaga University in Tochigi Prefecture, gave step-by-step instruction on how to put on these pieces of personal protective equipment, and more importantly, how to disrobe after caring for patients with — or suspected of carrying — the novel coronavirus.

Tomio has given such training to hospitals and clinics in Suginami ward since April at the request of the Suginami Public Health Center, which handles the ward’s response to COVID-19. Earlier in the day he toured the 97-bed hospital, which specializes in providing long-term care for elderly people, to advise on zoning, so it can properly control the movement of patients and staff in the event of an outbreak. (The hospital had no confirmed patients at the time of reporting.)

A nurse at Suginami Hospital demonstrates how to put on pieces of personal protective equipment.

While Japan seems to have ridden out the first big wave of the coronavirus pandemic, it is far from declaring an end to its fight with COVID-19. Health care facilities everywhere and of all kinds are finding the need to prepare themselves by acquiring know-how to minimize transmission risks, especially among front-line nurses and care workers, often while coping with a limited supply of medical equipment.

UTokyo Professor Yasuki Kobayashi, who arranged the training session at the hospital, has coordinated the dispatching of public health experts at the university, including researchers and graduate students at the School of Public Health (SPH), to help public health centers with their COVID-19 response.

Kobayashi says the work to match the needs of public health centers in Tokyo with the skills and intentions of participating members began in late March and took about two weeks. Then since mid-April, about 20 members have worked at public health centers in Koto, Suginami and Setagaya wards and at the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health.

In addition to providing expert advice at medical institutions, like Tomio did, they have engaged in duties such as fielding phone calls and logging patient information in the database, as well as active surveillance, which involves investigating the spread of COVID-19 at medical institutions and nursing care facilities where there was an outbreak.

Kobayashi said that the arrangements were made after the Japan Society of Public Health, an academic society of public health researchers and professionals including SPH members, reached out to public health centers in Tokyo, which have been inundated with COVID-19-related cases since mid- to late March.

Kobayashi added that not only UTokyo’s SPH but the other 13 graduate-level schools of public health in Tokyo have joined in the effort to assist public health centers in the city.

“In the past, students and faculty at SPH had participated in disaster relief efforts on an individual level, such as in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011,” Kobayashi said. “But the efforts this time are important in the sense that public health experts at the university responded to COVID-19 as a group and assisted institutions such as public health centers.”

A roster of 14 helpers

In Setagaya ward, from April 10 through the end of May, 14 graduate students from UTokyo, a majority of whom are licensed medical doctors, nurses and public health nurses, worked at the ward’s public health center under the supervision of UTokyo Professor and SPH Director Hideki Hashimoto.

Akiko Toratani, an official at the Setagaya Public Health Center, said help from UTokyo arrived when caseloads were rising sharply.

“We have had an unusually high number of phone inquiries from March through early May, averaging over 200 a day,” Toratani, who is also a public health nurse, said. “In the week of April 13, we had over 300 inquiries a day, exceeding 350 at our peak. Phones were ringing off the hook.”

Public health centers play a key role in Japan’s response to COVID-19, being the first point of contact for citizens who are worried that they might have contracted the virus. The centers also liaise with hospitals and clinics to order PCR tests and hospitalize those who test positive.

Setagaya ward has a population of 920,000, the largest in Tokyo’s 23 wards. It had 513 COVID-19 patients as of June 20, the second-highest number in the 23 wards.

The SPH students have engaged in a variety of duties at the Setagaya center, but only medically qualified members have fielded phone calls, Toratani said, adding that other duties include creating administrative documents, following up on health conditions of residents who have tested positive, and entering patient information in the database.

In dispatching helpers from the SPH, Hashimoto created a roster by breaking them into teams of three to five people each and making sure that medically licensed members were present every day. Hashimoto, a medical doctor himself, also showed up on some days to help, Toratani said, noting that she appreciated his advice especially when the center received calls that required delicate handling. Some callers had an underlying disease, often making it hard to determine whether their health conditions were caused by COVID-19 or their underlying disease, she said.

Despite involving as many as 14 students, who worked one or two days a week each, the operation has been smooth, she said. Toratani explained the expected duties only to the team that showed up on the first day; the team relayed the information to the rest of the students so well that she didn’t have to repeat the same explanation from the second day on.

“We really appreciate the help we got, as it came when we needed it the most,” she said.

On the other hand, Hashimoto says the dispatching of graduate students was intended not just to provide temporary helpers to public health centers but to give the students an opportunity to experience crisis management operations firsthand and think of ways to improve them.

Tomio (right) offers tips on how to prevent COVID-19 transmission at a recent training session in Suginami ward.

Easing anxiety among hospital staff

Back at Suginami Hospital, officials looked relieved after they got advice from the experts. The hospital had crafted its own zoning plan, which involved isolating COVID patients on the top floor of the four-story hospital building. After inspecting the building, however, the experts advised that they should plan to house COVID patients on the third floor instead, as private rooms on the third floor had better access to running water and space for removing the personal protective equipment.

“We have no expertise or previous experience on how to accept patients with infectious diseases,” said Yasuhiko Kuboi, head of administration at Suginami Hospital, after the training. “Our patients are all elderly and so are many of our staff, which means that, once someone gets sick, there is a good chance that the person could develop severe symptoms. So the staff were very scared. But we were told today that as long as we take basic preventive steps, we don’t have to be excessively worried. That was a huge relief.”

Tomio, who advised hospitals in Japan on how to prepare for the arrival of patients with the Ebola virus disease during the outbreak in West Africa in 2014-2015, says a textbook approach is not always possible at small and midsize hospitals that are not specialized in handling infectious diseases.

Supplies such as N95 masks and protective gowns are limited at many health care facilities, and their buildings are not specially designed to handle infectious diseases, Tomio said, noting that they have to think of ways to respond best with the resources they have at hand.

“Some facilities are so fearful of the virus that they rush to take excessive measures, but that could end up increasing risks by forcing unfamiliar procedures on staff,” he said. "If they know how to cover the basics, however, it reduces the risks and helps ease the anxiety the workers have. That’s very important.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake