Dialogue between philosophy and science Tokyo Forum 2022 underscores necessity for philosophy to address trans-scientific questions in an age of war, pandemic and climate change

Following their closing remarks at Tokyo Forum 2022, UTokyo President Teruo Fujii (center right with hands raised) and President Park In-Kook of the Chey Institute for Advanced Studies (center left) are flanked by session moderators of the two-day symposium. NHK World Japan executive anchor Miki Yamamoto, master of ceremonies of the event, is at far left.

Philosophy in the 21st century must address critical questions that cannot be solved by science alone, through dialogue with science at a time when humans face unprecedented challenges such as health and environmental crises. That was a key takeaway from Tokyo Forum 2022, which was held Dec. 1 and 2, 2022, and brought together more than 30 speakers from around the world.

University of Tokyo President Teruo Fujii set the tone for the two days of discussion in his opening remarks at the university’s Yasuda Auditorium. “Philosophy in the 21st century needs to build a new universality based on regionality and diversity that extends throughout the world,” Fujii said. “This universality must challenge the uncritical anthropocentrism of conventional history and be open to coexistence with things other than human beings, including ecosystems and nature.

“Science in the 21st century also needs to break away from unself-critical scientific supremacy, and strive to recognize its own limitations,” Fujii added. “This will require reconsidering the meaning of ethics for science.”

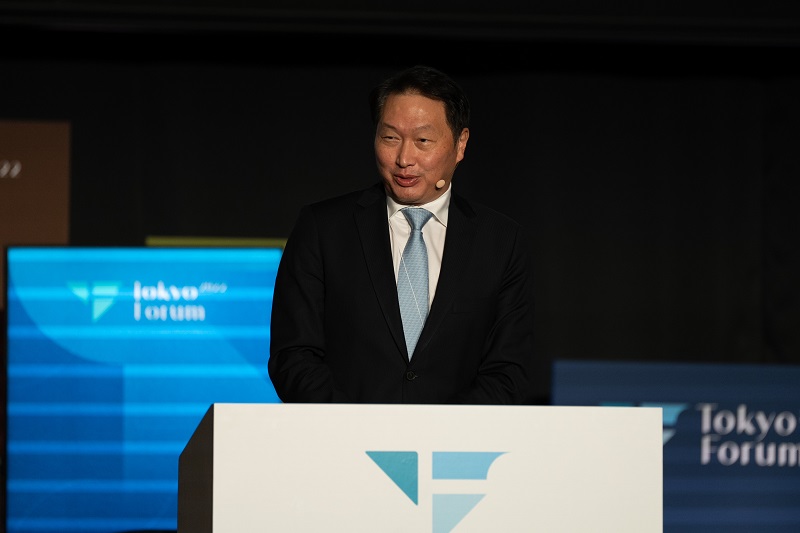

Chey Tae-Won, chairman of South Korea’s SK Group, echoed the sense of alarm about the problems humanity faces. “Today, we find ourselves in a long, dark tunnel, with no end in sight,” he said. Chey underscored the importance of being open-minded and learning how to embrace differences, while finding practical solutions with greater flexibility and diversity and thinking outside the box.

During their keynote addresses, former U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, President Mariko Hasegawa of the Graduate University for Advanced Studies in Japan, and President Paul Alivisatos of the University of Chicago in the U.S. discussed the role of philosophy in an age of rapid progress in science and technology. The main theme of this year’s symposium was “Dialogue between Philosophy and Science: In a World Facing War, Pandemic and Climate Change.”

A New Enlightenment essential

During the high-level talk session held on the first day, Professor Markus Gabriel of the University of Bonn in Germany called for a New Enlightenment that lays out a moral framework in which all humans can work together to tackle the unprecedented challenges we face today.

“The New Enlightenment, the era that I think is about to begin, delivers new modes of cooperation, philosophy and science in light of a particular understanding of what it is to do the right thing … and in light of understanding normativity as it runs through the socially and naturally complex systems that are evidently in crisis right now,” Gabriel said, speaking online from Hamburg, Germany.

He said that universality, one of the key elements in the New Enlightenment, has to be generated from the bottom up. “Human biology tells us that we are pro-social animals who flourish best under conditions of high-level cooperation, (which) helps us overcome geopolitical tensions and fights between identities,” Gabriel said. “For this reason, the new universalism has to be generated bottom-up by taking into account local cultural differences.”

The session included an in-depth discussion on the theme of “Dialogue between Philosophy and Science: Towards a New Enlightenment.” The other panelists were Lee Sukjae, professor of philosophy at Seoul National University; Professor Hirosi Ooguri, director of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe at UTokyo; and Professor Sayaka Oki of UTokyo’s Graduate School of Education. Professor Takahiro Nakajima of UTokyo’s Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia moderated the session.

The only natural scientist among the panelists, Ooguri put forward an argument as a physicist. Noting that scientists are very practical, he said “how to involve diverse groups of people to solve problems together” and “how to translate ideas into specific sets of methods of discourse” are becoming increasingly important. He added that scientists can bring a practical attitude to their collaboration with philosophers in these areas, such as the responsible use of science.

Lee touched on what he said was a “new type of connectedness or integration,” or new local universality, citing the example of how South Korean pop culture has taken the world by storm. “If you look at (the Emmy Award-winning South Korean TV drama series) ‘Squid Game,’ it’s a very local depiction of what’s going on within the confines of Korean society,” he said. “But the themes and issues that are emerging are not just unique to Korea, but express problems that (exist) all across the world. I think that kind of universality that is embedded in local context (is what) makes it very interesting.”

Relationship between philosophy and science evolved over centuries

After the session’s philosophers and physicist discussed the New Enlightenment, Oki, a science historian, gave a historical perspective to the discourse by telling the audience about the relationship between philosophy and science over the last several centuries.

Oki noted that philosophy and science were not separate in the age of the Enlightenment, the intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. For example, English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton (1643-1727) considered himself a natural philosopher. But the end of the Enlightenment saw the divergence of science and philosophy, as German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) observed, with scientists working in specific fields with narrower perspectives and giving less attention to the moral aspects of their research. “The role of philosophy diminished considerably during the 19th century, probably until the middle of the 20th century,” Oki said.

The situation changed dramatically during the latter half of the 20th century. In the face of trans-scientific problems involving moral, cultural and social factors, the importance of philosophy, especially ethical thinking, began to be reaffirmed in scientific research, Oki explained. “Trans-scientific problems … cannot be solved by science alone, though we cannot handle them without science,” she said.

Need for dialogue among diverse, different people

A panel discussion on the second day, titled “How Does World Philosophy Confront the Various Crises in the World?” followed up on this theme.

Session moderator Noburu Notomi, professor of the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology at UTokyo, said World Philosophy is a Japanese project launched in 2018 that aims to converge knowledge, including science, culture and everyday life.

Dermot Moran, professor of philosophy at Boston College in the U.S., defined the role of philosophers in tackling major challenges for humanity. “It seems to me that what philosophers must do in the face of turbulence, intolerance, injustice and barbarity is to continue to practice their profession, to be a light in the darkness, to remain open to dialogue, to invite discussion with the other and the stranger, and to promote new dreams, new goals, new concepts and new values,” he said. “Philosophy needs to cultivate a very strong sense of ourselves as bound by a common humanity, with a shared dependency on our planet Earth. We need a general acknowledgment of our vulnerability on the planet and our responsibilities to ourselves and to the planet as a whole.”

While Moran gave an insight into the role of philosophy from a Western perspective, two female philosophers from Asia included Asian and female viewpoints. Kim Heisook, professor emerita of philosophy at South Korea’s Ewha Womans University, said humanity has to focus more on different kinds and forms of rationality in epistemological perspectives, including those of Asian people and women. “Dialectical thinking must involve consideration of the marginalized, (which is) hidden from the view of those controlling technology,” Kim said. “Philosophers and scientists, including engineers, cannot but cooperate to solve unforeseen problems.”

Professor Suwanna Satha-Anand of the Department of Philosophy at Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University introduced “Right View,” or what the Buddha considered to be the correct way to look at existence, as a compass that helps us navigate the world in an era of pervasive distrust.

How to deal with environmental crisis, the prevalence of AI

During the two-day symposium, panelists discussed serious problems arising from the advance of science and technology, namely climate change, loss of biodiversity, and the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.

During Panel Discussion 1 on the first day, with the theme “Global Commons Stewardship as a World Common Value,” participants took up the environmental crisis for the third consecutive year.

UTokyo Executive Vice President and Center for Global Commons Director Naoko Ishii (on the big screen and on stage) moderates a panel discussion on Day One titled “Global Commons Stewardship as a World Common Value.”

UTokyo Executive Vice President and Center for Global Commons Director Naoko Ishii (on the big screen and on stage) moderates a panel discussion on Day One titled “Global Commons Stewardship as a World Common Value.”Many speakers during the symposium said humanity is not doing enough to address the environmental crisis. Naoko Ishii, director of UTokyo’s Center for Global Commons, who moderated the panel discussion, was one of them. After citing U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ remark in November at the COP27 climate change conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt (“We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”), Ishii said we need enablers to break the stalemate in stopping global warming.

Professor Jung Tae Yong of the Graduate School of International Studies at South Korea’s Yonsei University said the task of addressing climate change has been shouldered mostly by the public sector, but should be left to the private sector, which has more monetary and human resources.

Panelists also discussed sustainable development, including the need to redistribute global resources such as food, water, energy and infrastructure to developing countries that are suffering from damage and loss as a result of economic activities in advanced nations, in addition to providing low-interest financing.

Panel Discussion 5 on the second day followed up the discussions under the theme of “Complex Challenges of Security and Climate Change: Understanding Interconnections and Charting Future Responses.” Panelists addressed geopolitical factors, such as the U.S.-China rivalry, and problems of the capitalist system, which is holding back efforts to save the environment, in addition to the need to redefine what the good life is, with the help of philosophy.

UTokyo Professor Gentiane Venture (pictured on the big screen and seated at left on the stage) leads a panel discussion exploring how to live with robots and artificial intelligence. The panelists joining her on stage are (seated from right): Associate Professor Dominique Lestel of École Normale Supérieure Paris; Professor Hyoun Jin Kim of Seoul National University; Professor Emerita Yuko Harayama of Tohoku University; and Kim Yoon of Saehan Venture Capital.

UTokyo Professor Gentiane Venture (pictured on the big screen and seated at left on the stage) leads a panel discussion exploring how to live with robots and artificial intelligence. The panelists joining her on stage are (seated from right): Associate Professor Dominique Lestel of École Normale Supérieure Paris; Professor Hyoun Jin Kim of Seoul National University; Professor Emerita Yuko Harayama of Tohoku University; and Kim Yoon of Saehan Venture Capital.Loss of biodiversity, another result of scientific development, was discussed at Panel Discussion 3 on the second day under the title of “Toward Transformative Change for a Sustainable Future: Understanding the Diverse Values of Nature and Its Contributions to People.” Panelists discussed the need to recognize the value of nature, especially biodiversity, one of the planetary boundaries (within which humanity can make sustainable development) that have been severely compromised due to environmental destruction.

Panel Discussion 4, also held on the second day, explored how to live with robots and AI, under the theme of “What Future for the Society with Robots and AI? Economy, Ecology and Politics beyond Human Beings.” Panelists discussed how far robots and AI have evolved over the years, bringing both convenience and challenges to society. Professor Emerita Yuko Harayama of the Graduate School of Engineering at Tohoku University in Japan, said it is critical for humans to think out of the box and to be innovative to differentiate themselves from AI so that humans can live in harmony with it.

Following the wrap-up session, where the moderator of each session reported on the outcome of their discussions, Fujii, the UTokyo president, made this closing remark: “I really think academic institutions like us, the University of Tokyo, should be a place where various people can have meaningful dialogue with each other, to pursue truthful knowledge generation and to promote true science. I strongly hope that the next Tokyo Forum will also be a place where positive and constructive discussions about the future of our planet and human society can take place.”

Tokyo Forum 2022 was the fourth annual symposium held under the overarching theme of “Shaping the Future.” It was co-sponsored by UTokyo and South Korea’s Chey Institute for Advanced Studies to stimulate discussion on the best ways to shape the world and humanity.