Lessons from disaster (II): Disaster preparation for all circumstances

Jan. 17, 2026, marks 31 years since Kobe, Osaka and the surrounding region in western Japan were rocked by the 1995 Kobe Earthquake, while in March 11 we commemorate the 15th anniversary of the quake, tsunami and nuclear disaster of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred off the Pacific coast of Japan’s northeastern Tohoku region. Professor Kimiro Meguro, dean of the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies and Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies and editor of the book The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake Disaster and the University of Tokyo, published in 2024, explains how we can learn from the past to prepare for future disasters. (This article continues from “Lessons from disaster (I): History and Tokyo’s precarious circumstance.”)

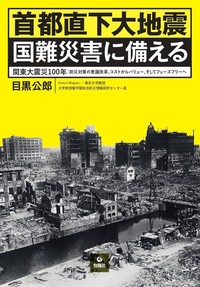

Source: Nishinomiya Digital Archive ©Nishinomiya City General Affairs Bureau

Stopping fire in its tracks

―― One of the major concerns for densely populated cities is the risk of fire after an earthquake. What can we do to prevent such fires?

Some say that we should strengthen public firefighting capabilities, but it would be impractical and unrealistic to maintain an excessively large firefighting apparatus dedicated solely to combat fire after major earthquakes, which occur only rarely. The city of Kobe suffered extensive fire damage as a result of the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. At the time, the city had a population of approximately 1.5 million people, with an average of about two fires per day and the public firefighting capabilities to handle four or five fires simultaneously, making the situation entirely manageable under normal circumstances. However, 53 fires broke out within the first 14 minutes from when the earthquake struck at 5:46 a.m. until 6 a.m., and 109 fires occurred altogether on Jan. 17, the day of the earthquake. The number of outbreaks was completely beyond the capacity of the public firefighting force to handle.

So, does this mean there is no solution for this situation? Not at all. We know what measures are effective for extinguishing or containing fires relative to their scale. For small fires, on a scale of about 1 tsubo (Japanese unit of area approximately 3.3 square meters), initial firefighting by civilians using fire extinguishers is the most effective method. Volunteer or professional firefighters are most effective putting out fires on a scale of 100-300 square meters, the equivalent of one or two typical houses. For even larger fires, however, such as those that cover over 1,000-5,000 square meters, or even 1 square kilometer, it is no longer a firefighting issue, but becomes one concerning the fire resistance of structures and urban planning. In fact, following the Kobe Earthquake, fires were contained through firefighting efforts in only 13.8% of cases. Roads and railways (at 39.9%); fire-resistant construction, firewalls, cliffs, etc. (at 23.6%); and vacant lots (at 22.7%) accounted for the rest.

The outbreak of simultaneous fires following an earthquake can overwhelm the capacity of public firefighting in terms of the sheer number of cases, but because these fires start small, they are just the kind of fires that can be effectively managed by civilians. Although firefighters may be able to respond to similarly small fires under normal circumstances, they cannot deploy to every single one of the many fires following an earthquake. This is precisely when citizen-led firefighting becomes crucial, but in Kobe, this approach could not be carried out successfully. There were five reasons for this, four of which stemmed from structural problems of the damaged buildings.

First, many houses collapsed. This meant that people on the front lines who otherwise would have been capable of extinguishing small fires before they spread, were trapped beneath collapsed buildings, preventing early intervention. Second, those who were not trapped rushed to rescue the large number of those who were, prioritizing that over firefighting. Because people are also expected to help in rescuing others following an earthquake, firefighting efforts got delayed. Needless to say, the solution to both the rescue and firefighting problem is to prevent buildings from collapsing. Third, fires that ignite under or inside collapsed buildings cannot be easily handled by untrained individuals. Fourth, when many houses collapsed, the rubble of the destroyed buildings blocked narrow roads, preventing access to the fire sites for both firefighters and civilians alike. And fifth, which could likely improve with education, people expected the fire department would rush to the scene and extinguish the fires as it had done in normal times, resulting in people missing the critical window to extinguish the fires themselves while the fires were still in their incipient stage.

For the aforementioned reasons, the first four are issues related to building damage, and unless they are resolved, the problem will persist. Fire spreads when it is not extinguished in its early phase, and the rate of fire outbreak is an issue almost directly proportional to the rate of building collapse. As I explained, firefighting becomes difficult when the building where the fire originated has been completely destroyed. Firefighting operations are carried out only after the shaking from the earthquake has subsided. This means the issue for firefighting is not the shaking but the amount of damage to the building at the source of the fire. As a result, in areas with a low rate of total building collapse, the rate of fire outbreak is also low. Even if a fire does start, the likelihood of it being extinguished is higher. In other words, ensuring the earthquake resistance of buildings and enabling early firefighting by civilians are crucial for preventing fire damage from earthquakes.

Reconstruction in the aftermath of disaster

―― What conditions and preparations are necessary to ensure smooth recovery and reconstruction after a major earthquake?

During the recovery and reconstruction efforts following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the shortage of administrative personnel was compounded by the challenge of securing enough engineers for reconstruction work. The number of projects that local construction companies in the disaster-affected areas could handle had reached a limit, which led to depending on contractors from outside the region and the outflow of construction costs from the affected areas.

Japan’s construction investment peaked in the 1992-93 fiscal year (ending in March 1993) at approximately 84 trillion yen (and GDP of 444 trillion yen). After that, engineers who had been directly involved in large-scale projects and highly skilled heavy machinery operators began to retire. By fiscal year 2010-11, just before the Great East Japan Earthquake, the construction sector had shrunk to about 50% of its peak size (to 42 trillion yen, with infrastructure construction and building construction markets each accounting for approximately half, with GDP at 511 trillion yen). Even if significant construction investment could be anticipated upon future large-scale disasters, technology cannot progress, let alone be maintained, without actual large-scale construction projects in the works. This is a major problem with the current state of both the caliber and quantity of engineers.

Construction investment increased significantly after the Great East Japan Earthquake, reaching 63 trillion yen in fiscal 2019-20. However, that increase was in building construction investment, while infrastructure investment remained at around 20 trillion yen. Regarding the severest damaged three prefectures in the Great East Japan Earthquake — Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima — their civil engineering construction market ratio in fiscal 2010 accounted for approximately 6.3% of the national total. This rose to 16.3% of the national total in fiscal 2014, when external support peaked. Similarly, an analysis of a Nankai Trough megathrust earthquake shows that the civil engineering construction market in all prefectures expected to suffer damage equal to or greater than that of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima would account for approximately 43% of Japan’s total.

In the Great East Japan Earthquake, the regions outside of the three severely affected prefectures, whose market ratio was 93.7% of the national market, supported recovery work and increased the three prefectures’ market by 10.0% of the total market. And in about 10 years, reconstruction work was largely completed, excluding areas in Fukushima Prefecture that were affected by radioactive contamination. In the event of a Nankai Trough Earthquake, however, even if 57% of regions outside the most severely affected areas contributed to recovery efforts, how long would recovery take? It is clear that the situation would be far more severe.

The outflow of recovery and reconstruction funds from the affected region has been an issue brought up since the Kobe Earthquake. When the demand for disaster response exceeds what the affected areas can handle, outside support becomes necessary, resulting in the outflow of recovery and reconstruction funds to regions outside the affected areas. Although spending for preemptive disaster resistance measures can be directed locally, budgetary provisions after disaster, even when they are made under severe circumstances, tend to flow out of the affected areas.

Disaster preparation for any situation

―― What should we be doing right now to prepare for future disasters?

The damage expected to result from a Nankai Trough Earthquake or Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake is expected to be far greater in scale than that of the Great East Japan Earthquake. They will each likely exceed Japan’s domestic capacity to respond, meaning funds would flow out of the country. As a solution to this, I have been advocating, since long before the Great East Japan Earthquake, for a new framework, “Iza-Kamakura System in the 21st Century,” which will be introduced later.

Currently, it is difficult to secure large-scale construction projects solely within Japan. Under the proposed framework, Team Japan (comprising general contractors) would pursue large-scale projects overseas, including in Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Europe. The team would consist of young, talented engineers who would maintain and advance technical capabilities on-site. And while doing so, skill development and fostering mutual understanding in collaborating countries will be of paramount importance. Japan should recognize that exporting its infrastructure expertise is vital for its own future disaster preparedness and the government should establish support systems to back up such efforts by Team Japan. Furthermore, Japan should establish agreements with partner countries ensuring specific support in the high likelihood of a national-level disaster by mid-century. If we fail to implement such a measure, we will have insufficient response power and be vulnerable to a substantial amount of post-disaster funds flowing out of the country.

We also need to modify our approach to disaster response and preparation. Since the Meiji Era, Japan’s approach to disaster response has been led by public assistance, namely, the government at all levels using public funds to plan and implement disaster countermeasures. However, given the ongoing demographic changes caused by declining birthrates and an aging population coupled with fiscal constraints and overall disaster risk, maintaining the traditional proportion of public assistance is impossible. Shortfalls in public assistance have to be supplemented by mutual support and personal funds, but the usual approach of appealing to people’s conscience or sense of morality as in the past has reached its limits. The keywords for future disaster preparation measures should be “from cost to value” and “phase-free.” Both the public and private sectors have traditionally viewed disaster management as a “cost” — what we need to do is change this to “value.”

―― What exactly does a phase-free approach entail?

It is difficult to justify investing in a framework that can only be utilized in times of disaster, which are limited in both time and space, not to mention that they are extremely rare. Therefore, the primary focus of future disaster management should be to create phase-free measures that enhance our day-to-day quality of life and operational efficiency, while also being readily applicable to disaster management. This approach would transform current measures, which are sporadic and whose effectiveness is unproven until a disaster actually occurs, and consistently deliver value to the people, organizations and communities responsible for implementation, while contributing to build social trust and enhance branding through sustained activity, even in the absence of disaster.

The current international assessment of Japan’s disaster risk is unfairly high. Although Japan is geographically located in an area prone to various hazards, and heavy concentration of the population, property and function in the Tokyo metropolitan area also increases risk, both the government and private sector have implemented disaster countermeasures that are quite high by international standards. However, these countermeasures are not being properly evaluated. There are two reasons for this: first, risk information on both governments and private sectors is often not disclosed publicly, leading to conservative assessments; and second, evaluation methodologies themselves cannot adequately assess these countermeasures. As a result, Japanese companies are significantly undervalued compared to European and American companies with similar performance levels. If regional and corporate disaster preparedness were properly evaluated and reflected in their value, implementing countermeasures itself would increase value. Functional decentralization would also be evaluated favorably, leading to progress on various fronts, including reducing concentration of the population, property and function in the Tokyo metropolitan area, which consequently would serve to mitigate future damage and loss significantly. Increasing the value of Japanese companies would also contribute to improving the quality of life and enhance prosperity during normal times.

Japan must take the lead in proposing appropriate assessment methods that can be applied globally, promoting them as international standards and enabling accurate risk assessments for disasters in Japan and around the world. Creating such an environment should be of primary importance to our nation for disaster preparedness going forward.

Kimiro Meguro

Dean and professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies and the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies

Received Ph.D. degree from the Graduate School of Engineering at UTokyo. Professor in the Institute of Industrial Science (IIS) at UTokyo since 2004 after working as a research associate, then associate professor at IIS. Served as director of the International Center for Urban Safety Engineering at IIS from 2007 to 2021. Professor in the Center for Integrated Disaster Information Research at the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies (III) since 2010, serving as its director from 2021 to 2023. Appointed and serving as dean of the III and the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies (GSII) since 2024. Author of numerous publications, including Shuto Chokka Daijishin Kokunan Saigai ni Sonaeru (“Preparing for a National Critical Disaster like the Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake”) (Junposha, 2023), as well as the editor of The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake Disaster and the University of Tokyo: Lessons for the Next Great Earthquakes, such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Inland Earthquake (University of Tokyo Press, 2024).

Interview date: Jan. 21, 2025

Interview: Yuki Terada, Hannah Dahlberg-Dodd