Out of the lab, into the field Improving public health around the world

The Division for Strategic Public Relations has published a magazine titled Future Society Initiative: Society 5.0 and the University of Tokyo. The magazine highlights some of the research projects at UTokyo registered under the university’s Future Society Initiative (FSI), a framework to bring together ongoing research projects that contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The following article, included in the magazine, takes an in-depth look at researchers who are actively tackling challenges in the area of public health, a common theme underlying a large share of FSI projects.

Researcher Chizu Sanjoba in the field in Mongolia. © 2018 Chizu Sanjoba.

Raiding rat nets across the Gobi Desert. Treating drinking water with ultraviolet LEDs in Asia. Mapping viruses with mobile phones in West Africa.

Researchers often work in places where resources and technical know-how are severely lacking. Their common goal: to bring the fruits of their labor to communities grappling with a public health crisis.

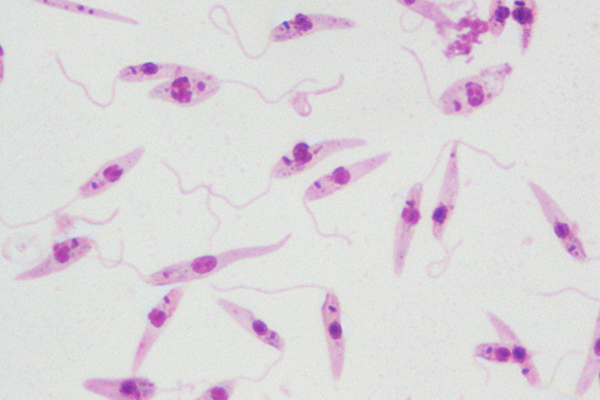

Chizu Sanjoba, an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, is an expert on parasitic diseases, particularly leishmaniasis. Leishmaniasis is an infection caused by Leishmania parasites, and spread through the bites of infected sand flies. The infection causes skin sores or extreme swelling of internal organs such as the liver and spleen.

One of 20 or so neglected tropical diseases designated by the World Health Organization, leishmaniasis affects people in poverty the hardest, due to their living conditions, which brings them into close contact with insects, livestock and other disease-carrying animals. Since the disease’s transmission cycles are complicated and different from area to area, Sanjoba argues that adopting the “One Health” approach, where research and interventions cover not only humans but also the animals and environments that surround them, is crucial.

“There are about 20 Leishmania parasites that cause leishmaniasis,” Sanjoba said. “There are at least 90 known species of sand flies that transmit the parasites. And then come animals that host the disease, from dogs to rodents to cattle. So there is a myriad of combinations of these. We need to devise a different control strategy in every country, while finding common knowledge we can share everywhere. This is not something that just one lab can do; we need to work with experts in various different disciplines.”

Hunting down desert rodents

Sanjoba’s research has taken her to many remote places in countries ranging from Turkey to Sri Lanka to Bangladesh, but one experience that sticks in her mind is a trip she took to Mongolia, where she tracked down desert rodents called great gerbils, which were thought to be a key pathogen carrier.

An international group of researchers including Sanjoba suspected that Mongolian people, many of whom are nomads, became infected with leishmaniasis after coming into contact with the gerbils. To prove this, they chartered three vans, hired a local driver and a cook, and hit the desert of the Gobi.

For a month, the researchers went hunting for one gerbil nest after another, setting up traps to catch the rodents. Then they examined the animals in a makeshift “clean bench” inside a tent to check if the creatures were indeed infested with Leishmania parasites. “We couldn’t take a bath for the entire month, we lined up behind horses to drink water when we found an oasis, and we stayed together in a tent and avoided going out at night so we would not be attacked by wolves,” she recalled.

Their research did prove that the gerbils carried the parasites.

What distresses Sanjoba, however, is meeting children in a village hit with leishmaniasis during a research trip one year, and then finding upon her return there the following year that they have died. She has also seen patients with clear signs of malaria who refuse to get their blood tested to see if they have the disease.

That’s why Sanjoba now considers education part of her work. She recently created, with the help of friends, a short animation film to teach Bangladeshi people the importance of using bed nets to avoid getting bitten by sand flies. She chose animation as her tool because many of those affected cannot read.

Water pollution along the Mekong

A desire to find real-life solutions also drives Kumiko Oguma, an associate professor of environmental engineering at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology. She has worked with communities in Southeast Asia since 2000, when, as a graduate student at UTokyo, she traveled along the Mekong River to study how human waste such as feces and urine released into the river upstream tainted the drinking water of people living downstream.

“I was shocked to learn that people without a water supply system had no option but to drink groundwater no matter how contaminated it was,” Oguma said. “Even when there was water supply, the tap water was often tainted with bacteria. Yet people had no option but to drink that water. It’s important for researchers to get detailed data about water contamination and write papers about it, but that alone does not make you feel you are helping local people. I had always wondered what I could do for the locals, beyond regular research activities.”

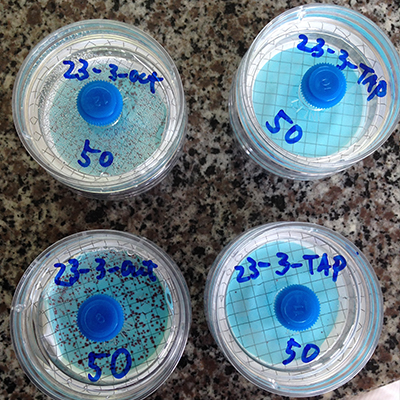

Oguma is now developing a compact water-disinfection device equipped with an ultraviolet light emitting diode (UV-LED).

Ultraviolet light is widely used at water treatment plants in many countries including Japan to kill a variety of bacteria, viruses and parasites, but all facilities use mercury lamps to emit the light. It was not until around 2010 that LED-emitting germicidal UV light became commercially available, according to Oguma.

The high costs of UV-LED make it difficult for the technology to be widely available in developing countries right now, but Oguma says UV-LED water-disinfection devices could become a viable solution once their prices come down.

Oguma explains that the technology has several advantages over mercury UV lamps. For one, it is totally mercury-free and more compact than mercury lamps. The LEDs begin functioning the moment their power is turned on, unlike mercury lamps, which take about 15 minutes to stabilize and start working.

In addition, the wavelength of UV emitted by the LEDs can be adjusted to target specific kinds of germs.

The technology could even prove useful in remote communities in Japan, where the population is rapidly aging and shrinking and where centralized large-scale water-treatment facilities may become unsustainable.

Oguma is currently doing a pilot test of home-based UV-LED devices in one mountainous community. The devices could also be useful at evacuation centers in disaster-affected areas or on remote islands, she said.

Tapping mobile phone data

Ryosuke Shibasaki, professor at the Center for Spatial Information Science (CSIS), has explored the use of mobile-phone data to monitor the spread of deadly epidemics.

For a project commissioned by the International Telecommunication Union, a United Nations agency, Shibasaki and his team of researchers visited the West African country of Sierra Leone about five times over a one-year period starting in late 2015, after the country was declared Ebola virus-free following the 2014 outbreak.

The purpose of his work there was to create a system that allows the country’s government to track and map people’s movements from one city to another based on anonymized mobile-phone call records and other “spatial” data — such as satellite images — so if there is another outbreak, the government can predict how the virus will spread and make quick decisions.

“Understanding people’s mobility is very important,” said Shibasaki, who has also worked with the governments of Liberia and Guinea, countries neighboring Sierra Leone and both severely hit by the Ebola virus.

“And there is a lot of data out there because everyone, including those in the poorest communities, use mobile phones, which are part of their civil infrastructure.”

Hiroyuki Miyazaki, a project assistant professor also at CSIS, is studying how to technologically empower nurses in Nepal as part of the EpiNurse project, an international, multi-institution initiative headed by University of Kochi professor and disaster nursing expert Sakiko Kanbara.

The project, launched after Nepal experienced a magnitude-7.8 earthquake in April 2015, aims to build a smartphone-based network where nurses can easily share information about the health conditions of local residents and the kinds of medical assistance needed. Miyazaki said that through the project, he wants to help develop skills and resources so nurses can improve their capacity to work effectively in their local area.

“Many local nurses rushed to help with disaster relief in the wake of the quake, but some of them lost their jobs because their pro bono work outside the hospitals was not well-understood,” Miyazaki said. “By making their efforts more visible to the public, I want to keep them from losing jobs so they can keep on playing a key role in their communities in periods of disaster or even during normal times.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake

Researchers

Related links

- Future Society Initiative Magazine

- UTokyo Future Society Initiative

- One Health Approach to Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases

- UV-LED Water Treatment Device for Better Access to Safe Water

- Dynamic Census: Developing Dynamic Population Statistics using Mobile Phone Data

- Research and Development of Spatial Information Tools for EpiNurse and Tranining Programs for Disaster Nursing