It’s only human UTokyo’s Humanities Center offers unique platform for researchers to collaborate with peers outside their specialty

A section of a hanging scroll created by renowned Japanese painter Taikan Yokoyama (1868-1958). This scroll with a male figure was loaned by Yoichiro Ushioda, chairman and CEO of building and housing material maker LIXIL Group and the financial supporter of the center located in the university’s main library. © 2019 Jouji Suzuki.

In July 2017, the University of Tokyo launched a research center with a big ambition: to create a new academic field around the humanities.

The Humanities Center (HMC) is a collaborative research consortium comprising eight UTokyo departments and institutions, including the Graduate Schools for Law and Politics; Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology; Graduate School of Arts and Sciences; Graduate School of Education; Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies; Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia; the Historiographical Institute; and the University of Tokyo Library System.

Eighteen months later, the center serves as a unique platform for researchers from fields across the humanities to meet and exchange ideas on their work. In a recent interview with UTokyo FOCUS, Mareshi Saito, a professor of Chinese literature and head of the HMC, explained how the center came to be, why studying the humanities is part of human nature and what he envisions as the center’s future role.

A year and a half has passed since the establishment of the HMC. Could you tell us how it all started?

We started making various preparations, including talking with potential sponsors, in the fall of 2015. But even before that, we had been hoping for a platform like this.

Researchers in science fields normally work in teams. This is true for Nobel Prize-winning scientists like Professor Tasuku Honjo at Kyoto University who won last year’s prize for physiology or medicine; or the huge team of UTokyo researchers involved in the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector in Gifu Prefecture.

Researchers in the humanities and social sciences, on the other hand, tend to work alone, especially in the humanities. That’s how the humanities have been studied until now.

Humanities researchers at UTokyo are all well-known individually as scholars. But in the course of our discussion for a new academic platform, we felt that there are few venues within the university for the humanities scholars to share their research and ideas with each other. And I believe what makes scholarly work interesting is the encounters you have with other researchers. But everyone says they have no time for such encounters. So I said, why don’t we make the time?

The HMC has instituted a system to allow researchers to concentrate on HMC-approved research projects for six months to a year, provided they can take a leave from their department, by bankrolling part-time instructors hired to teach classes in their place while they are away. We also decided to provide funding for researchers to invite fellow researchers from abroad so they can work together at UTokyo.

So researchers in the humanities had few opportunities to meet and exchange ideas with each other on campus?

That’s right. Researchers may have numerous opportunities to talk with their peers in the same department or lab. But the humanities have so many different specialties. I, for example, study literature, but there are others who study history or philosophy. While I specialize in East Asian countries, there will be another humanities researcher who specializes in Spanish politics, and so on. I hardly have any chance to meet such researchers. But when I do get to meet and listen to such people, I often find their talk incredibly interesting and we share many things in common. And at the end of the day, the humanities boil down to the question of what it means to be human.

So there are many questions that only humans share, and we can find common ground beyond our academic disciplines, labs or departments. But many researchers work in silos. This is partly because the university is so huge.

These are basic questions, but why study the humanities? What use do they have in our daily lives?

It is part of our nature as human beings to question who we are. I don’t think many cats wonder about such things. The humanities might not be useful at all. But everyone carries on with fundamental questions about their existence, such as why they were born into this world and what makes humans different from other animals.

Another point is, human beings may be the only creatures that are aware of their own mortality. Other animals might get a sense of their imminent death as they become old and fragile, but when humans reach a certain age they become aware of what’s going on around them, and realize, perhaps after seeing someone close to them die, that they too will die at some point. The humanities are an academic way of looking at the inevitability of human mortality, and the pain and joy that life brings us. So I feel that humanities research is here to stay. It is research based on an unstoppable human desire to find out who we really are. And sometimes these quests bear knowledge that we find useful, I think.

Do you think the humanities help to take our mind off the mundane?

By learning about one’s own existence apart from the here and now, we can look at ourselves from a distance and gain perspective. That’s one benefit of studying the humanities. Looking at yourself from afar can make you feel better. Good and bad things happen to all of us, whether we are adults or children, and certain things are beyond our control. Your abilities are limited and you face many limitations in life. You cannot avoid feeling negative in such instances. But the humanities help to widen your perspective by allowing you to look at things from outside your world, and making you realize that others share similar challenges and that you are not alone.

The HMC has two types of projects — planned research projects and open research projects. Would you tell us what kind of research they cover?

We have three “planned research” projects. One of them studies UTokyo as an academic asset. It aims to look back at the university’s history, approaching 150 years, and think of ways to utilize its accumulated capital, in the future. Another project focuses on the “theory and practice of symbiosis in the 21st century.” It’s research that has been accumulated over the years at the University of Tokyo Center for Philosophy on the Komaba Campus, currently led by (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences) Professor Shinji Kajitani, who runs cafe-style talks where members of the public and nonspecialists in philosophy get together to talk freely about a lot of things.

The third is an interview series with contemporary literary figures. We recently interviewed playwright Oriza Hirata, for instance.

Our aim is to become a bridge between the university and society, and have the campus be our venue. Of course, holding events off-campus, at the Kinokuniya bookstores, for example, can attract a lot of people. But I want to hold them right here at UTokyo.

Poetry readings and drama performances are frequently held on the campuses of American and European universities, but I don’t see many events like that at Japanese institutions, especially at national universities. Of course, researchers at the Faculty of Letters study literature, but I feel there’s also something symbolic about inviting writers currently engaged in the creative process to come to campus and talk about their work. Wouldn’t it be great to have a poetry reading by the iconic Sanshiro Pond (on the Hongo Campus), even though it might end up being a very itchy event as we fight off the mosquitoes there? (Laughs)

A runner jogs along the edge of Sanshiro Pond on UTokyo’s Hongo Campus. © Hiroyuki Shima.

And the open research projects?

The open research projects are aimed at supporting researchers’ free research activities. We do screen applicants but we want as many researchers as possible to participate, so the process is not as rigorous as the one for Kakenhi, the grants-in-aid for scientific research provided by the central government. We instead ask for the researchers’ input when they participate in our program and hold so-called open seminars about twice a month, where they talk about their projects in open forums.

The first open seminar we held was about military organization during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the last imperial dynasty of China, and how that affected the dynasty’s governing style. In another session, a researcher talked about sexual violence by the Imperial Japanese Army in the Philippines during World War II, focusing on why the Japanese military did what they did and the actual situation back then.

In another seminar I found interesting, a researcher gave a presentation on the famous 9th-century Japanese poet Ono no Komachi and how, during the Meiji Period (1868-1912), she came to be known in Japan as one of the world’s three beauties (along with Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, and Yang Guifei, a concubine of the great Tang emperor Xuanzong).

The HMC supports a variety of open research, yet of the seven researchers currently involved, about half of them have been attending all the open forums, even though many feature research that’s quite different from their own, and they often serve as commentators, too. Some unexpected insights have been gained from such exchanges. That’s what makes open research projects interesting.

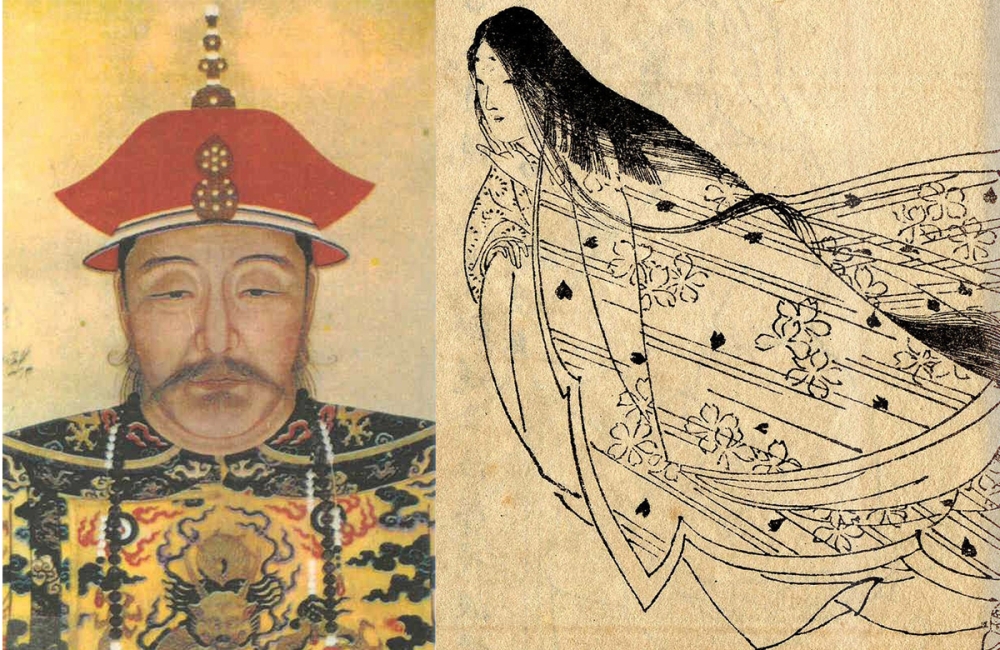

Portrait of Nurhaci (left), a Jurchen chieftain who later founded the Qing Dynasty, and illustrated image of Ono no Komachi, a Heian Period waka poet.

The HMC supports a variety of research projects, including ones concerning the military-led government of the Qing Dynasty and the popular saying

in Japan that mentions Ono no Komachi as one of “the world’s three beauties.” Wikimedia Commons.

The HMC aims to establish a new academic field. What kind of academic discipline would that be?

I wish I could tell you now ... (Laughs) I’m convinced that, by creating venues for academics to inspire each other, we will come up with a new field. Human curiosity and intellect have been constantly created in such a manner. I’m sure the researchers will find and nurture such fields themselves through numerous encounters at the center.

To be a little more specific, I hope the new kind of discipline will address contemporary and global challenges, by tying together studies currently separated by region or classification.

How do you want to promote the activities of the HMC, especially to people outside Japan?

I mentioned earlier that the center has set aside funds for researchers to invite peers from overseas as collaborators and let them work together at UTokyo. I think this will help us spread the word about our activities internationally. We’d like to create opportunities for UTokyo researchers to meet and talk directly with peers from abroad when they want to right then and there. I think it’s very important for overseas researchers to stay on campus for a while and nurture the feeling that UTokyo is their home.

The guest researchers this year hail from Switzerland, the Netherlands and Britain. Did UTokyo researchers have personal connections with them?

Yes. UTokyo researchers nominated foreign counterparts when they applied for funding from the HMC. Such connections are very important. In the future, I would like to enhance the ability of the HMC to connect UTokyo researchers, especially young ones, to scholars overseas. The university has university research administrators (URAs) to help with administrative aspects of research. By beefing up the number of staff who serve URA-like functions, I’d like to expand the liaison function of the HMC so it can help researchers develop international connections. People who study Japan, in particular, often say they hardly ever go overseas for research and don’t know where to go, either. We would like to advise such researchers on ways to expand their studies overseas, such as introducing international universities with good Japanology programs.

The entrance area of the Humanities Center features a folding screen created in Qing Dynasty China and loaned to the university by LIXIL Chairman Ushioda. © 2019 Jouji Suzuki.

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake