From little things big things grow A professor works to create sustainable future models through small architectural projects in developing countries

An informal community built in the wetlands of Turbo, Colombia

What can an architect do to create a sustainable future for the Earth?

Akiko Okabe, a professor of architecture at the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, studies policies that have a "supermacro" impact by implementing "supermicro" projects. For years, Okabe and students in her lab have worked on small-scale projects of buildings and public spaces in developing countries in Asia and Latin America.

Okabe’s approach is unique in that she tries to enable people to build better lives on their own without rejecting the "informal communities," such as slums, that have sprung up and developed spontaneously outside the scope of governmental urban planning.

Okabe, a Tokyo native, says that living in Mexico from age 8 to 10 profoundly impacted her outlook on life. Moving to Mexico City due to her father’s job, the young Okabe enrolled in a public school, where her classmates included adults who had resumed their education after dropping out of school when they were younger. In school, Okabe studied Mexican history and geography, even before she knew those of her own country.

“I learned the history of Mexico’s founding when I didn’t even know that Japan was an island nation,” Okabe recalled. “I learned how the indigenous people of Mexico were colonized by the Spanish, and then how Mexico eventually gained independence and became a democracy. But when I came back to Japan, I noticed that only half a page was devoted to Latin America in school textbooks. I was really shocked, realizing that the world looks completely different depending on your perspective.”

Okabe, who says the experience made her skeptical of anything regarded as a “fact,” went on to study at the University of Tokyo, majoring in architecture. After graduating from the engineering faculty, she got a job with world-renowned architect Arata Isozaki. Being posted to his firm’s Barcelona office, she used her fluent Spanish to help design a sports hall for the 1992 Olympic Games held in the city. She continued her research and to practice architecture in Europe, before returning to Japan and taking up a faculty position at Chiba University in 2004. In 2009, through a chance encounter with the proprietress of a traditional Japanese inn in the city of Tateyama, Chiba Prefecture, she was introduced to the seaside community of Shiomi in Tateyama and started a project to restore an old house there.

Valuable lessons learned

Professor Akiko Okabe at the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences

Shiomi is a traditional community consisting of some 50 households by the sea. A district whose history goes as far back as 1,000 years ago, Shiomi has long prospered as a fishing and farming community, thanks in part to its temperate climate and rich fishing resources.

Shiomi has thus kept functioning as a community even though its population has grayed. The members of the Okabe lab, who had assumed this rural community was in decline and that they could somehow help, ended up being taught a lot about community by the elderly residents, Okabe said.

“Even today, representatives from each household in Shiomi get together once a month for a meeting at a shrine to discuss community issues,” she said. “In such a small, close-knit place, the elderly residents taught our students the proper rules of the community, such as how to take out the garbage and greet neighbors.”

Okabe, who was asked to examine a dilapidated house in Shiomi, decided to replace its thatched roof. Thatching roofs of private homes used to be a community event, but because of the attrition of people with thatching skills the house had been abandoned. Okabe decided to replace the thatch little by little, over five years, enlisting the help of a young thatching professional from outside Chiba Prefecture and students from her lab.

The Gonjiro project, named so after the house’s longtime nickname, continued even after Okabe moved to UTokyo in 2015, and the property is still used for meetings of students from UTokyo and other universities, as well as for events involving Shiomi residents.

Okabe says the project, in which the students handled every process of re-thatching themselves, from harvesting the straw to recycling the old material as fertilizer, taught them how thatched-roof houses have helped preserve the scenery and the ecosystem of satoyama — an area of forests and mountains used for agriculture — and how they have helped maintain the community. It also served as a reminder of the often-forgotten truth that “needs” bring people together.

Students re-thatch the roof of an old house nicknamed Gonjiro in Tateyama, Chiba Prefecture.

People eat somen noodles that they catch in a bamboo water slide at an event held after the old house was renovated.

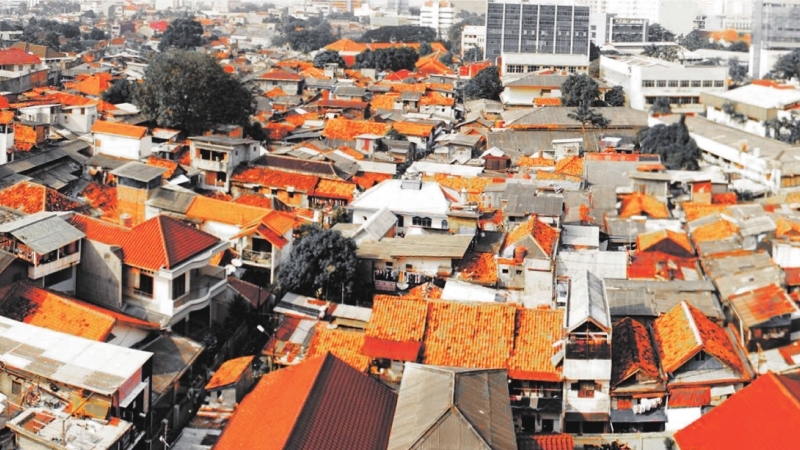

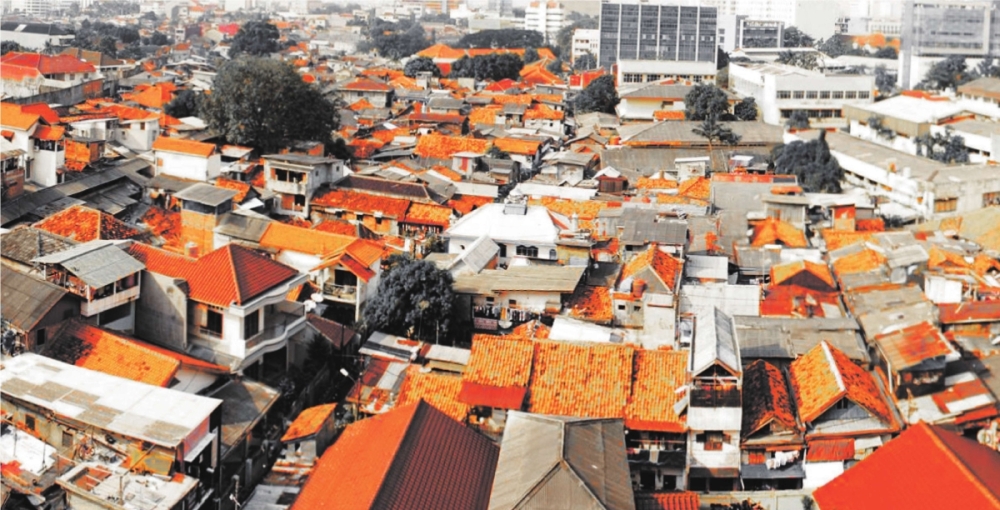

Since 2009, Okabe has also been involved in informal settlements in Cikini, a densely populated inner-city district in Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital. Students initially went there with a mindset that they would help improve the lives of local residents by bringing in technology and expertise from Japan, Okabe says. But such thinking, assuming a sense of mission, quickly dissipated when the group started interacting with residents and realized how vibrant and robust their lives were, she adds.

“The people there cherish their day-to-day life,” Okabe said. “Compared to them, students are busy thinking only about the future — about their future jobs and careers. They don’t live out their life today. Students realize by living and working with people in developing countries how little community experience they’ve had themselves, typically having grown up in a nuclear family in the suburbs. While they are architecture majors, they don’t necessarily know how buildings are made, unlike people in such communities, who can build their own homes. Interacting with such people often gives students opportunities to get down to the core and ask themselves, ‘What is architecture?’’’

Informal settlements in Jakarta’s Cikini district

An abandoned house that UTokyo student Atsuki Ryokawa stayed in and renovated in Quito, Ecuador

A house made of recycled materials

Atsuki Ryokawa

Atsuki Ryokawa, a second-year master’s student in Okabe’s lab, has traveled to Latin America many times. The first city he visited was Quito, the capital of Ecuador. In 2016, he participated in a project, along with collaborators at a local architect’s office, to resurrect an abandoned building in a historical area, by reusing waste materials only. He also invited neighbors and college students in the city to participate, in line with the long-standing custom among the indigenous Quechua people to build structures communally. He presented the project at a side event of Habitat III, the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, held in the city that year.

“We tried all kinds of recycling ideas, such as cutting discarded glass into pieces and turning them into window panels for the ceiling,” recalled Ryokawa, who spent nearly six months living in the same building that he renovated, which did not even have doors. He says the stay there was comfortable, as Quito, due to its high altitude, has a moderate climate and is free of mosquitoes.

“I drew pictures, recording the progress of the construction daily and uploaded them on Facebook. I think we succeeded in presenting a model of sustainable housing, which, if applied all over the city, can improve the lives of many people and reduce waste at the same time.”

Ryokawa also visited the seaside fishing community of Chamanga, hit hard by the Ecuador earthquake of April 2016. Over several visits, he interviewed a total of 74 residents on how their lives changed after the disaster. The results showed that, despite government efforts to move local fishermen and their families to newly built government housing inland, some residents stayed behind and used the damaged waterfront properties to store fishing equipment not only for themselves but also for those who moved inland. In his graduation thesis, Ryokawa analyzed the situation of Chamanga and proposed that government policy incorporate the residents’ ability to network with each other and shape their own environment.

The Chamanga district of Ecuador, where fishermen built houses close to the water.

Government housing units built inland after the 2016 Ecuador earthquake are on the left.

A new paradigm

Okabe plans more activities in Latin American countries, including Colombia and Argentina. In cooperation with EAFIT University in Medellin, Colombia, she currently studies an informal community set up in the mangrove swamps of Turbo, a port city in the country's northwest. The area was long undeveloped because of conflicts associated with drug trafficking, leaving the river as the only civic infrastructure through which to transport people and goods.

The descendants of people who were trafficked as slaves from Africa to Latin America during the colonial period settled in the wetlands after a long-standing civil conflict drove them out of areas upstream.

“They collected driftwood, which they used to build roads,” Okabe said. “When it rains, the ground swells with water and the roads begin to float. Providing new housing for these people might seem like the ideal solution, but it’s not. Without a job, they might end up in the drug trade. I would like to think how we can intervene in such a way that we can support their own efforts to carve out a better life.”

An informal community in Turbo in northwest Colombia. The road that residents built out of driftwood serves as a key piece of infrastructure there.

Okabe further aspires to present a new model for sustainable living from Latin America, which she considers her “home.” She says governments and universities in Latin America are aware that conventional development projects led to the widening of economic disparities among the people, and are open to policy proposals that try to incorporate the power of residents in informal communities to try to create a better environment themselves. She notes that Latin America’s stance contrasts to that in many parts of Asia, where authorities tend to rush development of impoverished communities in hopes that the economic effects will trickle down. By collaborating with local counterparts, Okabe says she wants to propose a new paradigm for a sustainable society from the developing world.

“I think there is a big difference between the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which preceded them,” she said. “While the MDGs envisioned the developed world as ideal models for developing countries to catch up to through technology transfers and so forth, they failed to achieve the ultimate goal of creating a sustainable Earth. Developing countries in fact have a lot of vigor and wisdom that the developed world has forgotten, as we have witnessed in our projects overseas.

“I believe that the SDGs were born out of the need for a new direction to build a sustainable society, by combining the wisdom of the developing world and the technology of the developed world. I haven't quite figured out yet how such a partnership would materialize, but I feel there is a genuine need for a new paradigm inspired by the developing countries.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake

Photos: The Laboratory of Akiko Okabe