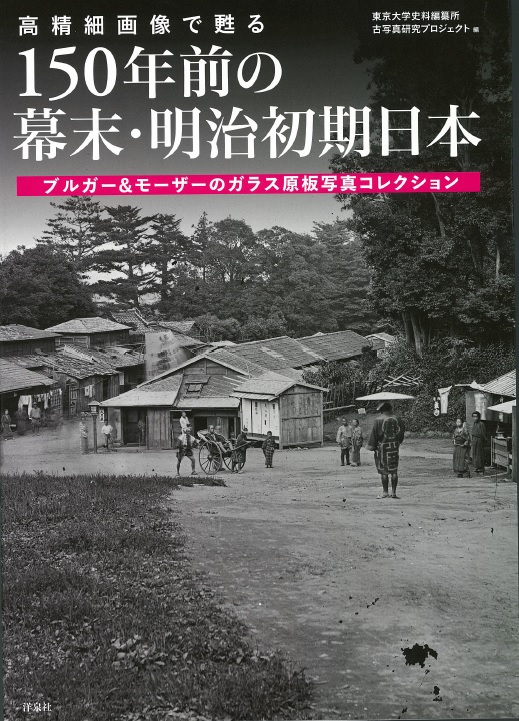

Old Japan photos come alive with modern technology Enlarged details reveal even 150-year-old graffiti

The Nihonbashi bridge in present-day Chuo ward, Tokyo, is shown in a photo believed to have been taken around 1872. Courtesy of the Kammerhof Museum.

What did Japan look like 150 years ago?

Glass plate negatives of photographs taken and collected in Japan by two Austrian photographers in the 1860s and 1870s can offer some answers. The hand-held plates, now stored in Austria, offer a unique window into Japan at a critical juncture, as the country emerged from over 200 years of seclusion under the feudal rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and quickly modernized itself at the dawn of the Meiji Period (1868-1912).

Since 2010, researchers at the University of Tokyo’s Historiographical Institute have made a total of seven trips to museums and libraries in Austria to photograph these “collodion” glass plate negatives — created through a process using collodion, a flammable, syrupy solution — with a high-resolution digital camera.

Toru Hoya, professor and director of the Historiographical Institute, poses in front of a panel of an old picture of Nagasaki, hung at the institute’s entrance. The picture, which shows part of the man-made island Dejima in the background, is believed to be the oldest existing shot of what was then the Dutch trading post. © 2019 The University of Tokyo.

The Austrian glass negatives are important because they are among the few photographic images that convey the landscapes and everyday lives of ordinary people in Japan from such a long time ago. Japanese photographers from this early period of photography did not leave behind many landscape photographs; they took portraits in studios, because that was their livelihood. Also, there are few glass negatives from this period left in Japan.

In addition, the unique process used back then, in which glass plates were coated with a photosensitive collodion solution and inserted into cameras while still wet, was capable of rendering fine detail. Therefore, if you take digital photographs of the negatives, turn them into positives and magnify them on PCs, you can see what’s photographed in astonishing detail.

“We have learned that the glass plate negatives, which had previously been regarded merely as an intermediate tool to create prints, in fact have great value as historical materials,” said Historiographical Institute Director Toru Hoya, who has led the old photography research project at the institute.

“Thanks to advances in digital technology and the arrival of high-resolution digital cameras, we are now able to extract a huge amount of information that even the photographers back then hadn’t realized they had recorded.”

Several enlarged prints of the Austrian collections, as well as the photographic process from the period, are currently on display at the Minato City Local History Museum in Minato ward, Tokyo. The institute is co-sponsor of the ongoing exhibition, “The Beginning of Relations between Japan and Austria — as seen through the lenses of photographers in the early Meiji period,” which commemorates the 150th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Japan and Austria this year.

The research project started in 2010 after the institute’s staff met with — and heard about the Austrian photographers from — Peter Pantzer, professor emeritus at the University of Bonn in Germany and scholar of Japanese studies.

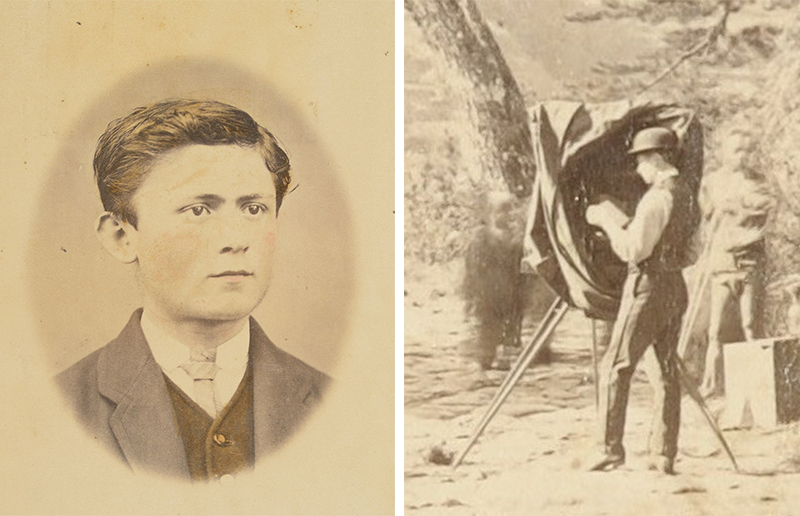

The two photographers — WiIhelm Burger (1844-1920) and Michael Moser (1853-1912) — arrived in Japan in 1869 as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s expedition seeking to establish diplomatic relations with the country.

Left: A portrait of Michael Moser while he was in Japan. Right: Moser develops a glass plate negative in a portable darkroom. Photos courtesy of Alfred Moser.

Burger, an official photographer for the expedition, left Japan with the mission after a few months. But Moser, who was only 16 at the time and worked as an assistant to Burger, stayed on for 6½ years. He spent his first few years in Japan working as a photographer for The Far East, originally a fortnightly English-language newspaper published in Yokohama. Both of them took and collected many photos of Japan, and when they left, they took with them hundreds of glass negatives, from which they could make prints to sell and distribute in their home country.

Hoya, who specializes in the history of Japan in the late Edo Period (1603-1867) and early Meiji Period, recalls the excitement he felt several years ago when he first saw a magnified portion of one of these negatives in Austria.

The photo showed several kimono-clad Japanese people on the street, including a man on a rickshaw, in front of a row of wooden structures. The exact location of the photo for long remained a mystery; a print carried in the Nov. 1, 1872, edition of The Far East newspaper bore a caption saying that it was taken “in the suburbs of Tokyo.”

An area west of Mount Atago in present-day Minato ward, Tokyo, is seen in a digital image taken from a glass plate negative. Courtesy of the Kammerhof Museum.

A close-up of the image shows a man on a rickshaw.

A road post on the right edge of this enlarged section shows the exact location of where the photo was taken.

Graffiti on a temple gate

The researchers found the negative of the photo, which is included in the photos from a private collection kept at the Kammerhof Museum in Bad Aussee, Austria, a town where he opened a photo studio after he returned from Japan. When they took a close-up shot of a road sign pictured in the negative with a high-resolution digital camera and enlarged the image on a PC, a street name became visible, thus allowing the researchers to pinpoint the exact location. The street name is Nishikubo-Hiromachi, in the present-day Toranomon area of Tokyo’s Minato ward.

“This was the first time we shot negatives as up close as we could, and we really got excited at what we found,” Hoya said.

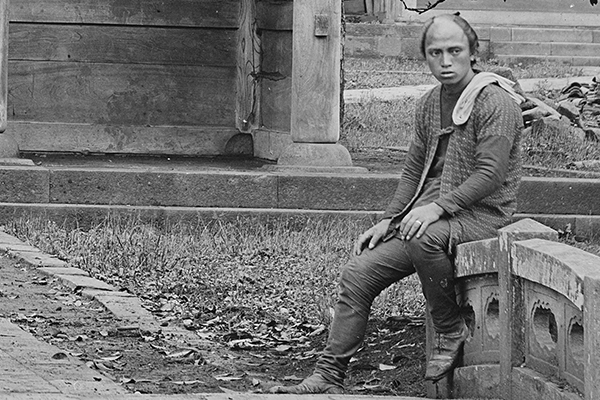

In another example, zoomed-in images have revealed graffiti on the walls of Buddhist temples and other structures that could not be recognized in their original size. Some graffiti depicted aiai-gasa, a drawing of an umbrella with names of two people in a romantic relationship, proving that the popular graffiti prevailed in Japan as early as the mid-1800s.

The main gate of Sengakuji Temple in present-day Minato ward, Tokyo, is shown. Courtesy of the Kammerhof Museum.

A close-up shot of a man shows that he is wearing a ring and Western-style boots.

A drawing of an aiai-gasa — an umbrella with names of two people in a romantic relationship — is shown scribbled on a wooden wall of the gate.

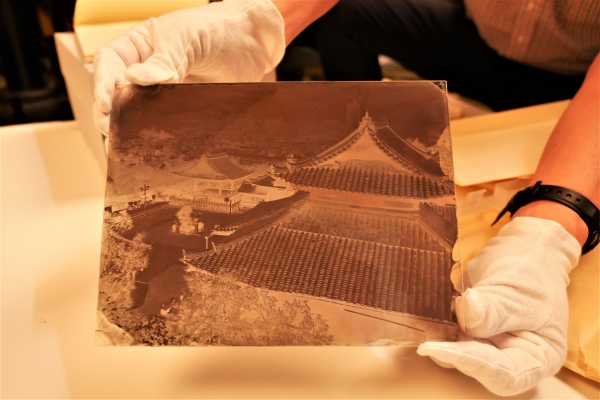

The institute’s research is unique in that it is a collaborative work between historians and photography experts. Akiyoshi Tani, a project member who is a photographer and researcher at the Conservation Laboratory of the institute, said the collodion glass plate negatives, which retain the chemicals the photographers used, as well as fingerprints and traces of image manipulation left by them, tell us a lot about the history of photography in this country.

Photographers back then created images using what are called collodion wet plates. In this process, a glass plate is coated with a mixture of a collodion solution — consisting of cellulose treated with nitric and sulfuric acid, and alcohol and ether — and a soluble iodide. Then the plate, while wet, is exposed in the camera. Photographers developed the plate in a portable darkroom to produce a negative, which they had to do before the plate dried; then they made a print by binding the photographic chemicals to albumin-coated paper. The whole process took numerous steps and refined skills. “Photographers from this period had to be a chemist as well as an artist,” Tani said.

Negatives offer clues on authorship

Moreover, the Burger and Moser collections include negatives that the two photographers bought from or were given by other photographers in Japan at the time. During this period, reprints from the negatives were sold under the final seller’s name, making it hard to establish authorship, Tani said.

Akiyoshi Tani (right) and Sayaka Takayama, staff researchers at the Conservation Laboratory of the Historiographical Institute, pose in front of a high-resolution digital camera they have used to photograph old negatives. © 2019 The University of Tokyo.

A glass plate negative that Tani and other researchers created recently using the old collodion photographic process, shot at Miidera Temple in Shiga Prefecture. © 2019 The University of Tokyo.

“In such cases, it helps to analyze the negatives themselves, as each of the negatives was made by hand,” he said. “Photographers mixed chemicals themselves, so depending on the kinds of chemicals they used and their ratios, the negatives and prints turned out quite differently. Negatives have a lot of information that prints don’t.”

The exhibition showcases enlarged prints of Austrian negatives that UTokyo researchers photographed with an 80-megapixel camera specially made to record images of cultural assets. Hoya said that the institute is in the process of procuring another high-resolution camera, this one capable of taking 150-megapixel photos.

“We will see how far we can go with high-resolution digital photography,” Hoya said. “We will study the old negatives down to the individual grain.”

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake

The exhibition “The Beginning of Relations between Japan and Austria — as seen through the lenses of photographers in the early Meiji period” runs until Dec. 15, 2019. For more information, visit the Minato City Local History Museum website at: https://www.minato-rekishi.com/exhibition/2019/08/150.html (Japanese)