Where is the world heading amid great-power rivalry? Report on Tokyo Forum 2019 Parallel Session “In Search for Common Security in an Age of Deglobalization”

This series of articles covers Tokyo Forum 2019, a new annual global forum to promote discussion and exchange ideas on the challenges facing the world and humanity. The University of Tokyo and Chey Institute for Advanced Studies co-hosted the inaugural forum on the university’s Hongo Campus on Dec. 6-8, 2019. Over 120 leaders from politics and economics to culture and the environment came from around the world to join discussions under the theme “Shaping the Future."

The great-power antagonism between the United States and China seems to be only intensifying geopolitical and economic tensions. Credit: Slay/Shutterstock.com

Where is the world heading amid the escalating great-power rivalry between the United States and China, the world’s largest and second-largest economies?

Participants of the parallel session titled “In Search for Common Security in an Age of Deglobalization” acknowledged that trying to find viable solutions to the great-power antagonism, which seems to be only worsening and intensifying geopolitical and economic tensions, is an uphill battle.

The session, held on Dec. 7, 2019, the second day of Tokyo Forum 2019, was organized by Professor Kiichi Fujiwara of the University of Tokyo.

The event took place just about a month after tens of thousands of people gathered in Berlin to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, which led to the end of the Cold War rivalry between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. But there was no festive atmosphere among the speakers as the intensifying conflict between the U.S. and its current rival, China, dominated their discussions.

In the session’s first panel, Professor Heng Yee Kuang of the University of Tokyo focused on artificial intelligence (AI). He pointed out countries’ interest in establishing global hegemony in AI: He quoted Russian President Vladimir Putin as saying in 2017 that, “Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world,” and cited U.S. President Donald Trump’s 2019 executive order aimed at establishing American leadership in AI.

Despite growing great-power competition in the high-tech sector, Heng said the international community still has a chance to cooperate in many areas, including in health care, to promote AI applications in a way to prevent the technology’s development from profiting just one side to the detriment of the other.

Ryo Sahashi, associate professor at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia of the University of Tokyo, talked about great-power competition and its impact on East Asia’s regional order from the Japanese perspective.

Although new emerging technologies should be developed without restrictions, U.S. regulations and policies are changing the openness of the innovation sphere, Sahashi said, noting that the U.S. is also restraining inbound and outbound trade with China, especially over information and communication technologies from China.

Sahashi also pointed out that, although Japan shares concerns with the U.S. for the need for a rules-based economy, it does not necessarily conform with U.S. policies on technology, as Japan is economically and technologically interlinked with China. Even though some regulations and export controls on technology for national security are necessary, hard decoupling of global value chains would be difficult for many economies, including Japan, to realize, he said.

Energy security affecting geopolitics

Professor Lee Jae-seung of Korea University spoke of energy transition and new geopolitics in Northeast Asia. Among the topics he touched on were a rapid increase in renewable energy output and the urgent need to deal with air pollution, especially that generated by fine dust particles.

He looked at the geopolitical implications of renewable energy development, divided into positive trends like reduced competition for fossil fuel supplies and bilateral policy bringing energy security to benefit both sides, and negative elements such as increased diplomatic tensions that hinder state-led collaborations.

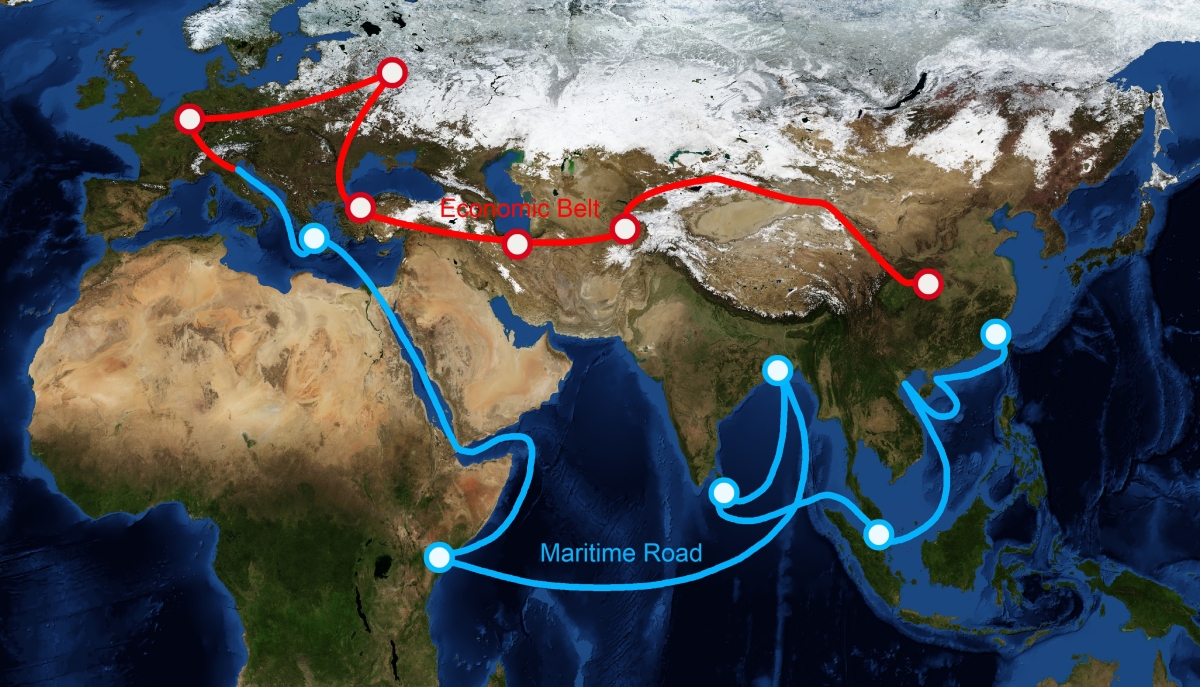

Lee cited new energy-related areas of competition, such as the ongoing contest between the Belt and Road Initiative, launched by Beijing in 2013 to bolster regional infrastructure over land and sea, and the Asia EDGE (Enhancing Development and Growth through Energy) initiative, launched by Washington in 2018 aimed at creating sustainable and secure energy markets throughout the Indo-Pacific region.

The Belt and Road Initiative, launched by China in 2013, aims to bolster regional infrastructure over land and sea. Credit: YIUCHEUNG/Shutterstock.com

Nonetheless, Lee expects advances in technology to increase the level of interdependence and multinational projects in the long term, with the market becoming more integrated. “Cybersecurity, digital infrastructure, nuclear safety and transboundary air pollution will require more common responses,” he said.

At the outset of his presentation, Assistant Professor Lei Shaohua of Peking University said that in the age of globalization, the proliferation of global value chains and international industrial structure has helped reshape international relations. As a result, he noted, the nature of security has changed, with the emphasis shifting from preventing war to protecting industry.

Lei cited industrial structure, cutting-edge technology and market size as the three most important factors in reshaping great-power competition.

He said he expects this competition to be stimulated by technological innovation in the years ahead.

New trend in great-power competition

Lei also said the recent state of Sino-U.S. relations reflects a new trend in competition between these two powers. Beijing and Washington are vying for supremacy in high technology, he said, noting that the U.S. trade ban on Chinese telecom company Huawei has not prevented China from commercializing new technologies for processing information and enhancing communications, such as AI and 5G.

Lei said the rivalry between the two global powers is in sharp contrast to the Cold War superpower confrontation between the U.S. and Soviet Union. He said the danger facing the world today is not war, but the possibility that two different systems of science and technology standards will emerge.

Lei stressed that China and the United States need to cooperate with each other in the same way they worked together to tackle the global financial crisis in 2008.

In the second panel session, Professor Kanti Bajpai of the National University of Singapore (NUS) noted that great-power rivalry in East Asia over the last three decades has been kept in check by a combination of a power imbalance or deterrence, economic interdependence and inclusive regional institutions.

He said this tripartite structure is under stress due to the changing power balance, skepticism concerning economic interdependence and the shakiness of the existing institutional architecture. Bajpai said building a strong bipolar balance of power, like the one that regulated the second half of the Cold War, by shoring up deterrence with reassurance and confidence-building measures and negotiating a comprehensive deal on computer-related issues and technology, would help stabilize the region.

Bajpai specifically advocated the establishment of an Asia-wide organization that would deal primarily with great-power issues — especially nuclear, maritime and cybersecurity matters. While Europe has the world’s largest regional security organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Asia has the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), initiated by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Bajpai noted that much of the ARF’s energy seems to be directed toward nontraditional security, which focuses on nonmilitary threats.

Bajpai said an Asian security organization that focuses on stability between the great powers seems increasingly necessary. Even though the great powers — the U.S., China and Russia — supposedly have reservations about such a regional security mechanism, he said there are reasons for each of them to participate, mainly to avoid increasing conflict, and at worst, unintentional war.

A panel of experts discuss changing technology and its regional implications at a Tokyo Forum parallel session on Dec. 7, 2019.

Professor Zhang Qingmin of Peking University recalled the three-stage path of China’s development that began during the country’s Cold War-era confrontation with the U.S. In the second stage, which lasted from the normalization of ties between Beijing and Washington in 1979 until recently, the two countries enjoyed their stable and mutually beneficial bilateral relations. The current, or third, stage, coincides with the outbreak of turbulence and uncertainty in the Sino-U.S. relationship in recent years, he said.

Zhang said the Cold War has never ended in East Asia, citing the existence of the 38th parallel, the cease-fire line from the Korean War (1950-53) separating North and South Korea, as a lingering case of Cold War division and rivalry.

But Zhang believes that what happened with Sino-U.S. relations during the Cold War can offer certain clues for the future. He said the U.S. needs to learn to adapt to China’s rise and should be ready to accept China as an equal, just as it recognized the communist government in 1979. He said this approach will likely help the two countries understand each other.

In the same panel session, Professor Peter Trubowitz of the London School of Economics, citing a globalization index computed by the KOF Swiss Economic Institute, noted that until the 1990s, Western voters were more positive about globalization than their governments. Since then, he said, Western governments have become more supportive of this process, while voters have shown less and less enthusiasm toward it.

Also joining the discussion was Professor G. John Ikenberry of Princeton University. He said the U.K. and the U.S. had been the two major standard-bearers of the international liberal order, and that in the past two centuries, these liberal democracies, with their partners in Asia and Europe, contributed to building a global system based on openness, multilateral rules, transregional institutions and universal principles.

The so-called Brexit vote in the U.K. and the 2016 election of Donald Trump as president in the U.S. have signaled the end of an era when the two countries served as the standard-bearers of the international liberal order, an expert said. Credit: Ink Drop/Shutterstock.com

But the so-called Brexit vote in the U.K., in which the country’s citizens elected to leave the European Union, and Trump’s election as president in the U.S. have put a stop to this endeavor, Ikenberry said.

While challenges posed by great-power rivalry are enormous, experts hinted at the possibility of creating a new liberal international order, one that perhaps incorporates non-Western perspectives. To achieve that, getting the citizens, not just governments, on board is essential, said UTokyo’s Sahashi in his summary of the session on the third and final day of Tokyo Forum 2019.

“So the real big task for us is ... how we can persuade the people about the merits of globalization and what kind of international society based on liberalism that we really want to achieve,” Sahashi said.

Videos of selected events are posted on the Tokyo Forum website.