The complex problem of inequality Report on Tokyo Forum 2019 Parallel Session “Inequality in the Global Era”

This series of articles covers Tokyo Forum 2019, a new annual global forum to promote discussion and exchange ideas on the challenges facing the world and humanity. The University of Tokyo and Chey Institute for Advanced Studies co-hosted the inaugural forum on the university’s Hongo Campus on Dec. 6-8, 2019. Over 120 leaders from politics and economics to culture and the environment came from around the world to join discussions under the theme “Shaping the Future."

Inequality comes in various types, including those based on gender or disability. Image: Shutterstock

Inequality has become a hot topic in recent years. It is a complex subject that raises many difficult and challenging questions. These include defining the concept itself, sorting through data to get a clear picture of various forms of inequality, and determining what can be done to address increasing inequality and its impact on contemporary society.

Widening income disparity tends to be the main focus when discussing inequality in Japan. But through the course of the parallel session “Inequality in the Global Era: Searching for an Inclusive Future,” held on Dec. 7, 2019, as part of Tokyo Forum 2019, it became clear that there are various types of social inequality, such as those based on gender or disability.

In the first presentation of the parallel session, Hitotsubashi University Professor Ryo Kambayashi described structural changes in the Japanese labor market and their impact on inequality in Japanese society.

Although many people believe that Japan’s famed lifetime employment system is in decline, Kambayashi pointed out that various data do not support that. “The Japanese employment system is still alive,” he said, noting that the percentage of those who are referred to as “standard” workers has remained the same for the past 30 years.

The major shift in Japan’s labor market, Kambayashi said, has been an increase in the number of nonstandard workers, along with a decline in self-employment. This shift has had a substantial impact on rural communities, he said, where self-employment has played a key role in maintaining political stability and in terms of formulating social welfare policy.

“The decline in the number of self-employed people has implications for what is happening in our society,” Kambayashi said.

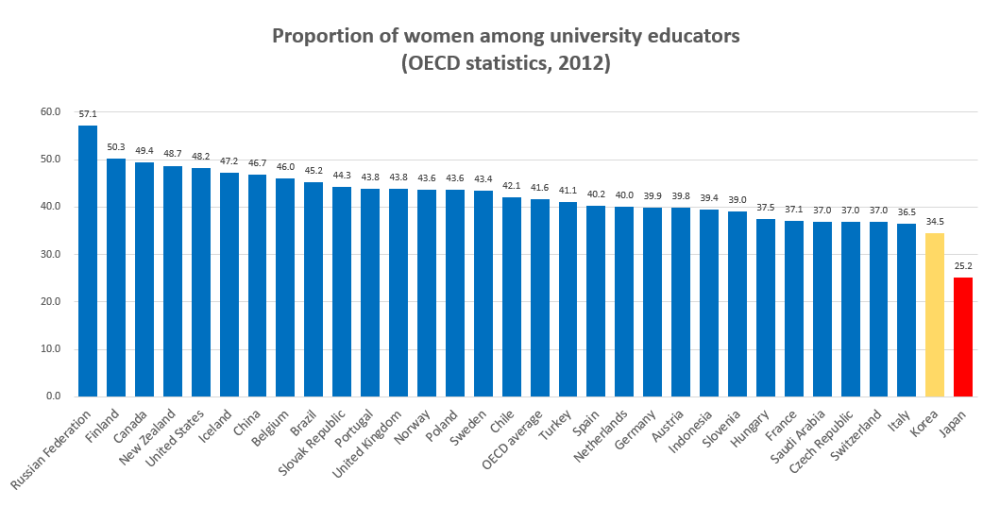

University of Chicago Professor Kazuo Yamaguchi presented his empirical study on economic gender inequality in Japan and South Korea. He showed that among OECD nations, Japan and South Korea have the highest levels of gender-based wage gaps.

Japanese women “horribly disadvantaged”

“For Japanese professional women, even if they have the same educational attainment and employment duration as men, their wages are much lower than men’s wages,” Yamaguchi said. “Women in Japan are horribly disadvantaged,” he added, noting how they are underrepresented in high-wage occupations. He said the situation is similar for women in South Korea.

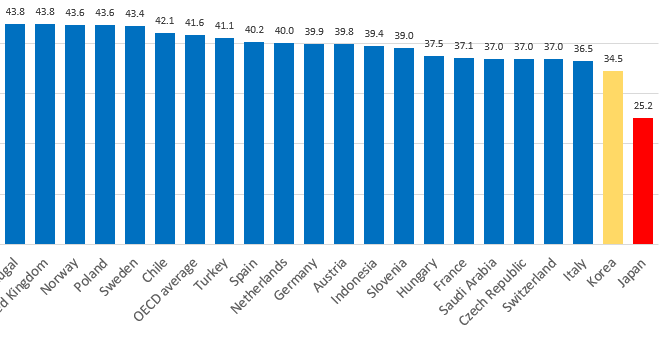

For example, Yamaguchi noted, Japan is the OECD nation with the smallest percentage of women among university educators and among physicians.

He said that women in Japan are doubly disadvantaged. Compared with other OECD countries, they are seriously underrepresented in high-wage professional occupations including physicians and college educators, and in managerial and administrative positions, where the gender wage gap is relatively small. Meanwhile, women are greatly overrepresented in certain human service occupations, such as child care and primary school education and health care support, and in jobs like routine clerical work, where the gender wage gap is wide.

Yamaguchi said one reason for the persistent gender-based wage gap in the two countries is derived from inequality of occupational opportunity.

“Firms in both Korea and Japan prepare different tracks for employees mainly based on who can work long hours,” he said, noting that the situation is more severe in South Korea. “It is difficult for married women in Korea and Japan to pursue an occupational career that demands long work hours, given the persistence of large gender inequality in the household division of labor.”

Yamaguchi presented an interesting paradox: gender equalization of educational opportunity further increases gender-based occupational segregation because women tend to become even more overrepresented in those occupations characterized by relatively low wages, despite such occupations being professional ones.

“The major obstacle against attaining gender equality in wages in Japan is neither the absence of equal pay for equal work nor the absence of pay equity,” Yamaguchi concluded. He said the biggest hurdle Japanese women face is unequal opportunities in attaining managerial or administrative positions and professional occupations with high socioeconomic status.

What can be done?

Yamaguchi posed the question on everyone’s mind: What can be done?

He said that employers have to change their mind about what they expect from employees, explaining that they need to place more emphasis on productivity per hour, as opposed to requiring employees work long hours.

He also said that his studies have shown that the less inequality of opportunity women face in the workplace, the longer they stay with a firm, the less the gender wage gap is, and the greater the labor productivity of the firm is, on average.

University of Tokyo Professor Akihiko Matsui then discussed how people with disabilities are treated unequally in the economic sphere. He said it is important not to label them as one group, but rather to treat them as individuals. Matsui added that markets cannot be relied on to address inequality based on people’s disabilities. Regulation is needed, he said.

The first two presentations in the afternoon session focused on inequality in South Korea. Seoul National University Professor Yee Jaeyeol said that developed East Asian countries face many challenges in terms of inequality.

He pointed out that economic development is not just about economic growth as expressed in terms of gross domestic product. Yee said it is also about creating a “good” society where the key metric is quality of life, and where equal access to opportunity is guaranteed for all kinds of people.

Professor Song Ho Kuen of South Korea’s Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) noted that spending on social welfare has been increasing in South Korea under pro-labor President Moon Jae-in. However, he claimed that this has caused many small businesses to go bankrupt, due to the rise in the minimum wage and restructuring of working hours.

The problem, Song said, was that the government rolled out its social policies too fast. That was largely because of the pressure on South Korean presidents to realize their policy agenda within the single five-year term in office they are allowed under the country’s constitution.

Professor Joakim Palme of Sweden’s Uppsala University suggested how we can tackle the problem of inequality in his presentation, “Social investment as a strategy of equality.”

He claimed that inequality is increasing in aging societies, and that investment in capital tends to have a greater return than investment in labor, as pointed out by French economist Thomas Piketty in his landmark 2013 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Experts discuss the limits of traditional redistributive policies like social security in addressing inequality during the parallel session “Inequality in the Global Era,” held Dec. 7, 2019, as part of Tokyo Forum 2019.

Broad concern

“This creates inequality,” Palme said. “There is broad concern about this trend.”

Palme placed the issue of climate change in the context of inequality. “Countries that are more unequal have more difficulty with implementing measures to fight climate change,” he said, adding that dealing with climate change presents both challenges and opportunities.

Palme said that traditional redistributive policies like social security are not enough to reduce inequality. “We have to move beyond Robin Hood,” he said. “If you want to look at inequality, you have to look beyond the welfare state and look at investment in human capital.”

He said equal distribution of human capital is needed in order to reduce pre-distribution inequality. And that requires a basic rethink of things like the “male breadwinner model.”

“If you want to change the gender contract, you have to change the way men work and care for children,” he said. “This is not about ending the family — it’s about changing relationships.”

However, Palme pointed out that there is no quick fix when it comes to reducing inequality. “It takes decades to implement these kinds of social policies,” he said.

The Q&A after Palme’s presentation and the wrap-up session that followed raised several interesting issues. One member of the audience asked how measuring levels of social inequality can be standardized.

Yee said that because of the disconnect between objective numbers and subjective perception, multilevel data need to be collected. But he noted that such data can be difficult to access across different countries.

Another member of the audience said that most governments are run by wealthy people, adding that if such political systems continue, the inequality gap will increase and destroy society.

The danger, Palme said, is that political systems are increasingly dominated by populists offering quick, easy solutions to problems like inequality.

Matsui noted the historical trend of inequality between nations. Inequality, he said, is not only a problem faced by individual countries, but is also a global problem. He said that unless we solve it, we cannot solve the inequality problem.

As the discussion’s organizer, UTokyo Professor Sawako Shirahase said that inclusion is the key concept to develop a sustainable, more equal society, noting that the challenge is to face reality and work together to build a better future.

Videos of selected events are posted on the Tokyo Forum website.