Centuries-old scroll, maps at your fingertips

The Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo is home to a vast collection of historical materials related to Japan from the 8th-19th centuries including national treasures. But some of the institute’s holdings have been too bulky to be shown or studied in full, as they often measure several meters in length and width.

But today, such works are at your fingertips. In December 2021, the institute released two digital archives of its important works from the 17th century — the Ryukyu Kuniezu (three hand-drawn maps of the Ryukyu Kingdom, which used to rule present-day Okinawa Prefecture) and Wako Zukan (a picture scroll depicting Japanese pirates who were active on the coastlines of China and Korea in the 14th-16th centuries). Both works can now be viewed easily and in amazingly fine detail through the institute’s website. Not only that, the archives have made refined searches of texts and images possible, which come handy not only for researchers but also anyone interested in history.

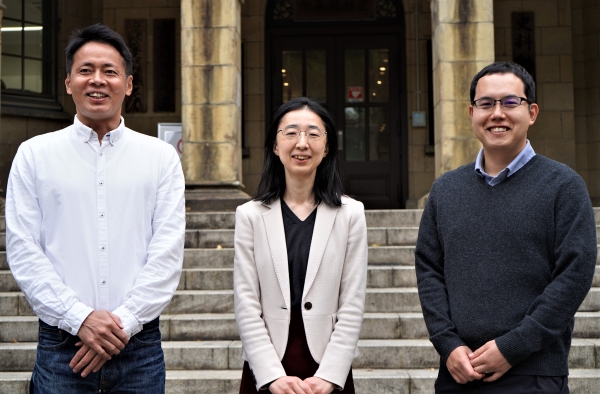

Associate Professor Satoru Kuroshima, who headed the project, says the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the demand for the institute to digitally share historical documents, as in-person access became severely restricted.

“Researchers at the Historiographical Institute have traditionally made it their mission to make accurate copies of historical materials by traveling to places where the originals of such materials are preserved,” Kuroshima said. “In recent years, we have worked to digitize the materials and make their images public. With the onset of the pandemic, researchers have been barred from surveying historical materials firsthand. Digitization of the materials has become all the more important, because researchers find it difficult to study them otherwise.”

Kuroshima noted, however, that the project came with a range of challenges. The Ryukyu maps, designated a national treasure, depict three groups of Okinawan islands in the mid-17th century, and measure over 3 meters by 6-7 meters each. Researchers decided to scan them digitally, but before doing so the maps, made of paper, had to be unfolded and their numerous wrinkles smoothed out gently, a process that took 1 1/2 months and for which conservation specialists at the institute were mobilized. Then the researchers put them in custom-made cardboard boxes, carefully carried them down the institute’s stairs and transported them about 50 kilometers to the east by truck to the National Museum of Japanese History in Sakura, Chiba Prefecture, where the maps were spread out in a large room to be scanned.

The Wako scroll was relatively wrinkle-free as it’s made of silk. The researchers asked photography experts at the institute to take high-resolution photos of the entire 5.2-meter-long work, which required seven images that were later digitally stitched together by outside specialists, says Associate Professor Makiko Suda, who studies Wako history.

But what was truly challenging was creating a database that showcases research findings in an engaging, easy-to-understand way. Suda recalls that the patched digital image of the scroll was of such high resolution and its file size was so large she could not open it on her computer. That’s where Assistant Professor Satoru Nakamura, an information science expert, came in.

Joining the institute in 2020 to accelerate efforts to digitize its holdings, Nakamura formatted all the files according to the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), an international standard for managing and sharing images.

“IIIF has made presentations of extremely large-size images easy,” Nakamura said. “The technology allows users to zoom in to see the finest details of the images, just like zooming in to see location details on Google Maps.”

Nakamura also accommodated Suda’s request to add annotations to various parts of the scroll. Most historical picture scrolls are accompanied by text explaining what is depicted. However, Wako Zukan, which was created in China by the first half of the 17th century, contains no such text. The archive provides interesting details on the scroll, which describes, over several scenes, the pillaging of Chinese villagers by Japanese pirates known as Wako and the pirates’ eventual defeat in a battle with Ming dynasty soldiers.

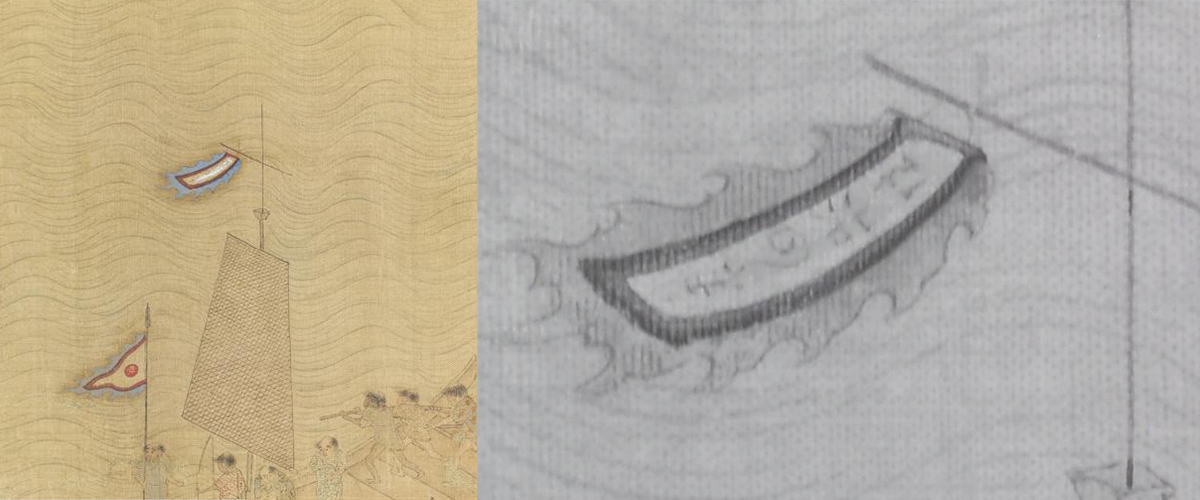

In fact, many details about the picture scroll remain unknown, leaving ample room for research. Suda herself made a major discovery in 2010 when she examined the scroll using infrared rays. While the scroll, which the institute purchased about a century ago, was believed to be about Wako pirates, it wasn’t quite clear which year’s battle the scroll depicted and against whom the pirates were fighting. She found the year of the scene — 1558 — subtly hidden beneath paint on the pirates’ flag, by examining the part closely through infrared photography with the institute’s photo experts. She also found letters on another flag that read “soldiers from heaven,” which confirmed that the opposing forces were Ming dynasty soldiers.

The infrared images, which shed light on the academically significant details of the scroll, are embedded in the archive, and users can quickly switch to them while viewing the original scroll.

“Advances in information sciences have given historians new research areas to explore,” Suda said, noting that through the archive, the researchers now know that the scroll features as many as 350 people. “It never occurred to me, until we began this project, to count the number of people depicted in the scroll.”

Kuroshima, who studies the Ryukyu maps, says he hopes the archive will be used not only by academics but also by the public.

“The archive can be shown easily on a smartphone or a tablet, so children in Okinawa can learn what the old landscape in their hometowns was like by comparing it with a contemporary map,” he said. “Or tourists in Okinawa can call up the archive while sightseeing, comparing the coastline of the area they are seeing with what it was like 380 years ago. … I encourage many people to use this archive and tell us how we can improve it.”

The Ryukyu maps can be viewed at: https://www.hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/collection/degitalgallary/ryukyu/en

The Wako Zukan scroll can be viewed at: https://www.hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/collection/degitalgallary/wakozukan/en

(The sites’ interface is primarily in Japanese only.)

Interview/Text: Tomoko Otake