On the front lines of Japan-India exchange | Discover Our People An alumnus uses his lifelong relationship with UTokyo to bring two countries closer together

-

- Shrikrishna Kulkarni

- President of the UTokyo Alumni Association of India (Class of 1991, Master’s degree, Graduate School of Engineering)

Areas of research: Robotics and automation

Country/Region of origin: India

A great-grandson of internationally renowned figure Mahatma Gandhi, Shrikrishna Kulkarni, known familiarly as Krishna, came to the University of Tokyo as a graduate student with a desire to see the world. After parlaying his studies and experiences at UTokyo into a notable career in the engineering field, he now gives back to his alma mater, working to bring more Indian students to UTokyo and Japan in general through his activities as the president of the UTokyo India Alumni Association and also as the co-founder of the UTokyo India Office.

A desire to see the world

Krishna grew up on a university campus in Ahmedabad, a city in the western Indian state of Gujarat, where his father was a professor. Although Krishna dreamed of becoming an Indian Air Force pilot, his family and friends directed him towards engineering, a popular career field in early-1980s India. Upon receiving an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering, Krishna started working at a company in Mumbai. But as a young man, he wanted to see the world.

For most Indian youths back then, the only opportunity to go abroad was to pursue graduate studies. A colleague of Krishna’s father suggested that since robotics and automation interested Krishna, he should consider graduate school in Japan. Having visited Japan once as a boy, Krishna thought, “Why not?” He was thus introduced to Yoichi Kaya, an engineering professor at the University of Tokyo. Kaya agreed to admit Krishna into his lab in the Department of Electrical Engineering as a research student, and Krishna came to Japan in January 1988. Initially unable to find housing, Krishna stayed with an elderly couple in Tokyo’s Jimbocho district for his first few months.

Alone in Japan and knowing little Japanese, Krishna had to clear the Department’s five-subject comprehensive entrance exam to become a regular student. Although he was unprepared, he notes that “when human beings are put in situations of challenge and adversity, they always rise.” And rise he did — after putting all of his energy into studying, he not only passed the exam, but was one of the top scorers for his year. When he heard the news, he bicycled back to Jimbocho to tell the elderly couple. “They started crying,” recalls Krishna. “I did not know the value of the University of Tokyo in the Japanese psyche. And then the grandpa took me to various shops in the neighborhood — the tobacconist, greengrocer, fish market, pachinko parlor — to tell everyone that I had passed. It was a very big thing.” He then became a master’s degree student in the lab, where he specialized in control engineering, a key aspect of automation and robotics.

A professor's wise guidance

Named after Kaya and then-Associate Professor Yoichi Hori, the Kaya-Hori Lab totaled about 20 students and staff, and all members, except Krishna, were Japanese. Due to the timing of his arrival to UTokyo, the intensity of his studies and the remote location of his lab, Krishna interacted little with other international students. Instead, the lab was his family. They went on trips together, and Hori even invited Krishna to his home for dinner. “In Japanese teacher-student relationships,” says Krishna, “they don’t just teach you a subject. They bring you up as a human being, and they have a say in your life.”

Krishna experienced the power of this relationship when looking for a job. Kaya introduced him to Seiuemon Inaba, the chairman of FANUC, a world-famous Japanese robotics company. After visiting FANUC’s headquarters near Mount Fuji to meet with Inaba, Krishna decided to follow Kaya's recommendation and start working there.

An invitation to India

After Krishna had worked at FANUC’s headquarters for three years, Inaba suddenly invited him to Christmas dinner. Over dinner, Inaba laid out his plans for Krishna; he wanted to move Krishna out of R&D and into management. Subsequently, he rotated Krishna through almost all of FANUC’s departments. After nearly a year of intense training, he called up one day saying he wanted Krishna to go to India and launch FANUC there. At 30 years old, Krishna went to India, and by 31, he was the country head and managing director of FANUC India. He ran it for 10 years, building it up to become one of the largest factory automation companies in the world.

The day before Krishna’s departure, Inaba, Kaya and Krishna dined together. There, Inaba asked Kaya if there was something he wanted for Krishna, and Kaya replied that he wanted to make sure Krishna doesn’t forget his Japanese. Therefore, Inaba sent Krishna to India under the condition that every week, Krishna would send a handwritten report on FANUC India operations in Japanese to him. Krishna did so unfailingly for 10 years, and he visited Japan monthly to back up his reports. “It was really hard learning,” Krishna reflects, “but it gave me strength. Thanks to that, no matter how many years pass, whenever I come back to Japan, I can start speaking Japanese naturally.”

A proposal from UTokyo

Around 2008, a few years after Krishna had left FANUC and was then country head for Panasonic India in Bangalore, a Japanese man named Hiroshi Yoshino came to the company, asking to meet with him. Once Krishna heard that Yoshino was from UTokyo, he immediately agreed. Yoshino, a UTokyo alumnus and longtime resident of India, told Krishna that UTokyo planned to start an office in the country, and sought his advice. Krishna deemed it a fantastic proposal, and suggested locating the office in Bangalore. With Krishna’s help, the UTokyo India Office opened in 2012.

Krishna speaking at the 2019 Homecoming Day. A video of his entire speech can be found here: https://todai.tv/contents-list/2019FY/Gandhi-150/02

Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has made the UTokyo India Office the base for Japanese universities, including UTokyo, to promote Japan to Indian students as a study abroad destination. As part of the organization’s activities, Krishna has visited universities across India with Yoshino, sharing his experiences and how his choice to study in Japan changed his life. “There are many role models for Indian students who want to go to the U.S. or Europe, but there are very few for those who are interested in Japan,” Krishna explains. “So I am willing to stand there.”

Krishna also helped Yoshino establish the UTokyo Alumni Association of India, or Akamonkai India. While Yoshino took care of the Japanese side, Krishna wrote the organization’s bylaws. UTokyo named Krishna Akamonkai India’s first president, and he served from 2012-2015. Later, citing his past achievements and knowledge about Japan, UTokyo requested that Krishna serve again from 2018. He accepted, calling it a “labor of love.” “A university is bigger than any individual,” he explains. “I mean, the University of Tokyo is like my mother in some ways, and you don’t refuse your mother. My heart doesn’t want to refuse.”

The UTokyo India Office is the “vanguard for achieving UTokyo’s India vision,” Krishna says, and the Indian alumni network is indispensable in realizing this vision. Akamonkai India’s activities include sponsoring short-term programs in India for UTokyo students and representing UTokyo at Japan study abroad fairs throughout India. Over 100 members strong, the association also has semiannual meetings for networking and reporting on alumni activities.

When UTokyo holds its yearly Homecoming Day in October, alumni from across Japan and the world converge upon the Hongo Campus to reminisce about their university days and participate in lectures and events. In 2019, UTokyo contacted Krishna, asking him to speak at a Homecoming Day event commemorating the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. “There you are again — when the University asks, you don’t say no,” reiterates Krishna. Honored by the invitation, on Homecoming Day 2019 he spoke to nearly 200 audience members about Gandhi and his relevance in today’s world.

A deep sense of gratitude

Over the decades, Krishna’s affection for UTokyo remains unchanged, but his relationship has evolved into one of thankfulness. “Nowadays, my strongest internal feelings are of gratitude, so I want to give back,” he says. “If I ever see opportunities by which I can repay UTokyo, I try to. I want to provide something from which UTokyo can benefit.”

UTokyo has benefited from Krishna’s activities with the UTokyo India Office and Akamonkai India. Thanks in part to the efforts of Krishna and others at these organizations, the number of Indians studying at UTokyo and Japan as a whole has roughly tripled, from 29 (541 in Japan) in 2012 to 92 (1,607) in 2018. Krishna wants to see these numbers increase further, but cautions that universities must do more than set hard targets. Unlike businesses, which tend to prioritize numbers and quick results, universities operate on timescales of decades and centuries, and should focus on long-range fundamentals. “A university education is not a business, ultimately. It’s a lifelong relationship. So don’t look at this as a 100-meter race. It’s more like a marathon.”

A couple of suggestions for international students

Reflecting on his experiences, Krishna offers two recommendations for those studying in Japan: first, to remember that coming to Japan was your choice, and to focus on positives when here. “You reap what you sow. Let’s say I have 50 seeds in front of me. Which of those do I want to plant, so that they become trees? You will have, as in my case, a gamut of experiences. It’s up to you to decide which of those experiences you want to focus on.”

Krishna also says that learning Japanese should be one’s top priority. Since students nowadays can take classes online instead of going abroad to learn, “What is it you’re learning by coming physically here?” he asks. “It’s human interaction. And if you know the local language, that makes it so much more beautiful. It gives you a window into every facet of your life. You must immerse yourself. That’s all. The rest, UTokyo will teach you.”

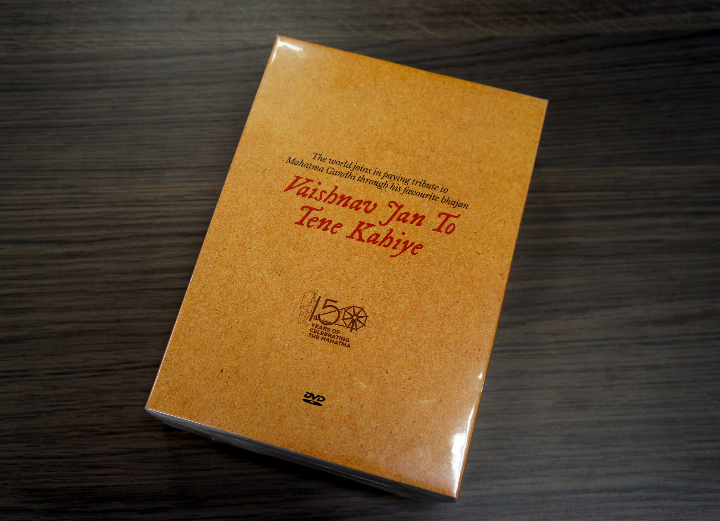

“Vaishnav Jan To Tene Kahiye”

Artists from 150 countries sing Gandhi’s favorite song on his 150th birth anniversary

Krishna brought to Japan a limited edition DVD he received from the Government of India. Made to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth, the DVD features artists from 150 countries singing in Gandhi’s native Gujarati language his favorite bhajan, or hymn, “Vaishnav Jan To Tene Kahiye” (“One who is a follower of Vishnu”). The lyrics of the song, which was close to Gandhi’s heart, describe the characteristics of those who lead a virtuous life. Krishna gave the DVD to UTokyo President Makoto Gonokami during Homecoming Day for donation to the University Library, with the hope that many people could benefit from seeing the powerful and unique performances of this song.

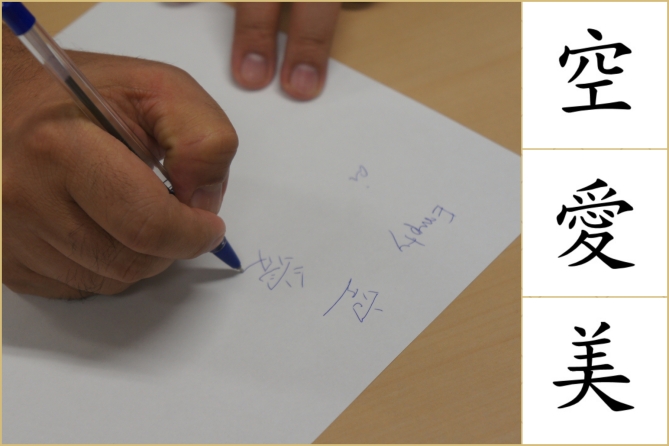

Emptiness, love and beauty

“If you have these three, you need nothing else”

Krishna’s three favorite kanji characters are 空 (kara; emptiness), 愛 (ai; love) and 美 (bi; beauty). As he wrote them, he explained his appreciation for each one. To get something new, you must empty your heart. Love is an indispensable aspect of life that needs no teaching. Finally, finding the beauty in everything makes life wonderful. “If you have these three,” he said, “you need nothing else.”

Interview / Text: Whitney Matthews