“I’m a Hanshin fan, but I liken my research to soccer” How forcing a breakaway is sometimes useful in the world of art history

| Japanese Art History |

“I’m a Hanshin fan, but I liken my research to soccer”

How forcing a breakaway is sometimes useful in the world of art history

Professor Yasuhiro Sato is well-known for his studies of Japanese art history, particularly with regard to the works of painters like Ito Jakuchu and Soga Shohaku. Meanwhile, he has also been a devoted fan of the Hanshin Tigers baseball team for almost 50 years, but in this article he makes an analogy between his own research and the game of soccer. His personal specialty, he feels, is not the precision shot, but dribbling in an audacious breakaway.

By Yasuhiro Sato By Yasuhiro SatoProfessor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology |

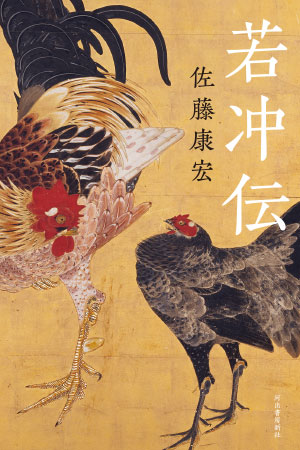

(Kawade Shobo Shinsha / 2019 / 2,400 JPY + tax)

I was a third-year undergraduate when I first learned of Ito Jakuchu as a painter who had been active in Kyoto in the 18th century, and this encounter ultimately led me to specialize in Japanese art history. My recent critical biography of Jakuchu, entitled Jakuchu-den (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2019) also incorporates my own previous research into the life and art of this great artist.

Jakuchu’s paintings are beautiful and robust. That sensory joy was my starting point. Art history, however, means not getting caught up in the contemplation of one’s own feelings – it entails our desire to think about things from the other side, from Jakuchu’s standpoint. When trying to understand Jakuchu, we need to examine specific questions, such as what sorts of paintings he drew on as sources of inspiration for creating his own works. That is, unless we clarify the extent to which he drew on existing materials and techniques to learn how much can be attributed to his own individuality, we cannot really describe his expression as unique.

The painters of the Edo period were unlike contemporary artists. Being able to paint according to one’s own whims and expecting someone to buy the work – such a model of production would have been exceptional. In most cases, painters would take orders and then create works to suit their clients’ preferences. This was basically the model of production that Jakuchu pursued after he retired from running a wholesaler that lent out space to grocers to become a professional painter. On the other hand, Jakuchu’s most important work, the Doshoku sai-e [Colorful Realm of Living Beings] (now held by the Museum of the Imperial Collections Sannomaru Shozokan), consists of thirty hanging scrolls featuring intricately colored paintings of flowers and birds that he created as a personal offering to Shokoku-ji temple. Why a mere craftsman might have done something like that is a question that piques our interest.

Having uncovered a Chinese poem by a poet who saw the Doshoku sai-e during its production, sought out other instances of the use of the term sai-e, and reflected on the circumstances of the work’s production and its donation, my own inference is that this work was motivated at least in part by Jakuchu’s wish to commemorate the soul of his father. I also learned that Jakuchu was supremely confident that the Doshoku sai-e would remain worthy of appreciation in the distant future – arguably for all eternity. Furthermore, from my analysis of his expression, I also speculate that this series may serve in part as a figurative representation of the deeper contemporary anxieties and desires felt by Jakuchu and the people of Kyoto in his day. I regard painting not only as the expression of individual painters, but something woven by the societies in which they lived.

Setchu kinkei-zu [Golden Pheasants in Snow]

From the collection Doshoku sai-e [Colorful Realm of Living Beings] (Museum of the Imperial Collections Sannomaru Shozokan)

The white paint (powder) representing the snow is applied separately in complex shapes, including holes, without painting over the verdigris hues of the needles. This results in the creation of an uneasy beauty, as though the world were being melted away by pale acid.

In most cases, no definitive evidence survives with which to prove the interpretation I have advanced with regard to this figurative representation of the past. In Yuna-zu: Shisen no dorama [Bathhouse girls: Dramas hidden in their gazes] (Chikuma Shobo, 2017), I made a brave attempt to restore a painting for which half of the screens had been lost. Likewise, in several of the articles included in E wa katarihajimeru daro ka: Nihon bijutsushi o tsukuru [Let the picture tell its tale: Rethinking Japanese art history] (Hatori Shobo, 2018), you could say that I give free rein to my imagination to gather up and rearrange the few surviving pieces of always only fragmentary jigsaw puzzles to speculate about what might actually have happened.

Some researchers eschew such studies as being unempirical, but for my own part, generally speaking, I prefer to make as thorough an investigation as I can of those matters for which this is possible, and then to attempt rather bold interpretations. Research is not a solitary endeavor. It is a pursuit in which we receive passes from those scholars who precede us, that with our own dribbling and passing we might get the ball to those who come after us, aiming ultimately at the goal. In other words, I am myself a piece in the game of history, and it is sometimes necessary to force a breakaway to get the ball moving toward the goal.

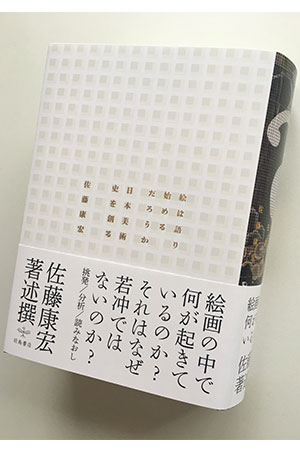

(Hatori Shoten / 2018 / 12,000 JPY + tax)

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 38 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2019.