Laying bare the reality of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture With the use of VR technology

| Western Art History |

Laying bare the reality of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture

With the use of VR technology

Virtual reality (VR) technology has become a familiar presence in our lives. In fact, its impact is being felt even in the world of art history research. Armed with the latest in 3D scanning techniques, Associate Professor Kyoko Sengoku-Haga has penetrated deep into issues surrounding the reproduction of ancient sculptures and the identification of their creators. Here, she shows how VR technology offers us a glimpse of reality from over two millennia ago.

By Kyoko Sengoku-Haga By Kyoko Sengoku-Haga Associate Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology |

The Latin for art is “ars,” which, while originally having the meaning of “skill,” remains nonetheless familiar to us as the etymological origin of the English term. Yet when we hear that the Greek word for art is “techne” (τέχνη), from which we also derive words such as “technique” and “technology,” we might feel that the term is a bit out of place.

However, in ancient Greece, the artists were unquestionably first-rate technicians. When the technology for casting life-size bronze statues was developed in the latter decades of the sixth century BC, it seems that people not only admired the tanned radiance of life-size images of nude males expressing such lifelike movement, but even felt the uncanny sense of discomfort that we ourselves feel in the presence of realistic robots (Figure 1).

On the other hand, while ancient Rome is famous for its construction technology, its massive buildings were also often adorned with huge numbers of statues. This was made possible by a precision reproduction technique for marble sculpture that was devised in the first century BC. A large number of precision copies were produced from a single original by creating a plaster mold from it, carefully measuring the points of the surface in three dimensions using a compass or similar tool, and then copying these onto marble blocks.

Riace Warrior Statue A

Circa 460 to 440 BC

Discovered in the waters off the coast of Riace Marina, near the southern tip of the Italian Peninsula. National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria. A valuable original bronze statue, rather than a copy from the Roman period.

Polykleitos

Doryphoros (“Spear-bearer”)

A first-century marble copy (the original dates to circa 450 to 440 BC). Excavated from a palaestra (training ground) at Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Polykleitos

Diadumenos (“Youth tying a fillet around his head”)

A marble copy from circa 100 BC.

(original dated to circa 420 BC)

Excavated at Delos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Let’s examine the technical capabilities of the Greeks and Romans by using today’s latest technology. The Doryphoros, by the 5th century BC Greek sculptor Polykleitos, was copied many times during the Roman period. Although the original bronze statue is no longer extant, copies from the Roman period do survive in the form of marble and bronze statues (Figure 2). As a test, we made 3D-scans of four high-quality copies and juxtaposed the resulting 3D models on the computer. We found that despite the fact that the angles of the arms and legs varied for the individual copies (likely because they were copied part by part) and slight differences of scale (perhaps caused by bronze shrinkage), the shapes of the faces and feet were almost identical, to within 2mm even in places with many errors. Their reproduction techniques were surprisingly advanced.

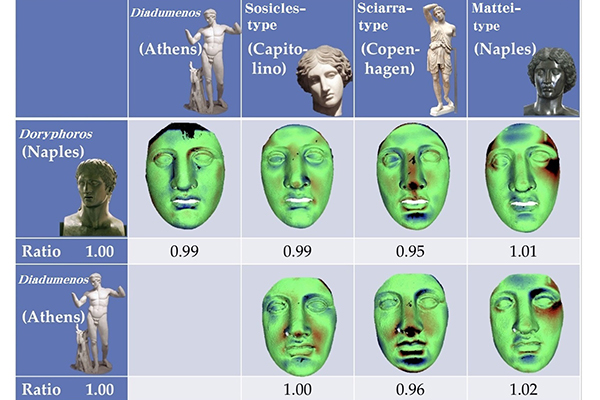

A 3D shape comparison of the faces of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros and Diadumenos with three “Amazon” statue types (Takeshi Oishi Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo)

With such precision, we should also be able to compare the shape of the original via the copies. A later work by Polykleitos is known as the Diadumenos (Figure 3). When we created 3D models to compare the Roman-period copies of these two works, we again found that the shapes of their faces and feet matched – Polykleitos had saved the original mold of the Doryphoros to use as the basis for creating the original mold of the Diadumenos. Such ingenuity in improving the efficiency of the work evokes the spirit of the technician more than of the artist.

In that case, then perhaps we could also use this method of comparing three-dimensional forms to identify creators. According to a classical text, it once transpired that several sculptors were each to fashion their own statue of an Amazon woman, with the best work to be decided by mutual agreement. As a result, first place was awarded to Polykleitos, second to Phidias, and third to Kresilas. Exactly three types are also known among copies of the Amazon statues dating to the Roman period. However, researchers’ opinions are divided over which of these is the work of Polykleitos, with little prospect of settling the matter. So, we scanned the heads of these three types of Amazons and compared them with the Doryphoros and Diadumenos. When we did, amazingly, we found only one that constituted a perfect match (Figure 4, Sosicles-type). 3D technology is thus rather useful for the study of ancient sculpture.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 38 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2019.