More than just a game of cat and mouse

More than just a game of cat and mouse

Cats are adored as pets nowadays, but in the past, there was another reason why they were kept. People in the olden days treasured cats’ ability to catch mice. We asked a historian to explain, using materials archived at UTokyo, the relationship between “useful” cats and human society — a relationship that cannot be described merely as one between “spoiled cats” and “cat lovers.”

Cats and history

By Shigeo Fujiwara By Shigeo FujiwaraAssociate Professor of the Historiographical Institute |

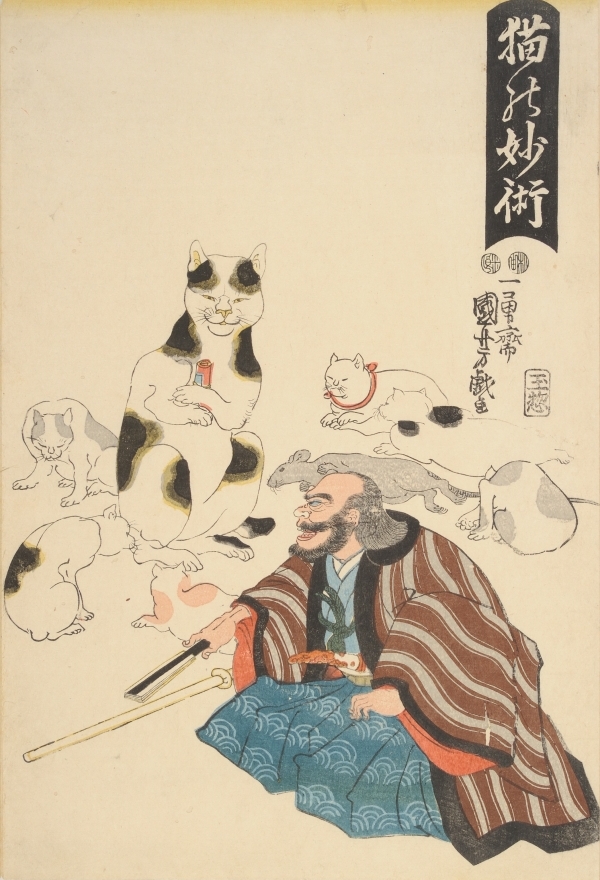

Picture 1: Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Neko no Myojutsu” (The Cat’s Masterful Technique), Kouka 4 – Kaei 5 (1847-1852). Owned by the Historiographical Institute

Picture 1 is a multi-colored woodblock print called “Neko no Myojutsu” (The Cat’s Masterful Technique) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, an ukiyo-e artist in the Bakumatsu period (mid-1800s). A large cat that is hard to describe as “cute” is holding a scroll, with a samurai sitting there looking furious. Ordinary cats surround the big cat with a captured rat lying on its side. According to a different version of this illustration, “Furuneko Myojutsu-setsu” (The Explanation of the Old Cat’s Masterful Technique) with notes written on the top, the subject of the print is a fable describing the ideology in the Chinese philosophical work Zhuangzi, explaining the secrets of martial arts (included in the essay collection “Inaka Soshi”).

One swordsman (I see he has a wooden sword next to him) was troubled by a large rat in his house. Afraid of this rat, he tried to make his cat catch it, but the cat ran away. So, he gathered a number of cats with a reputation for catching mice, yet they flinched at the sight of the rat, and not even attempts to strike the rat with his wooden sword worked. So, he borrowed an undeniably famous old cat from six or seven towns away, but it didn’t appear to be either smart or agile. However, when the old cat was put in the room where the rat was, the rat froze up and the cat walked over sluggishly and caught it. That night, the cats that failed to catch the rat asked the old cat to teach them the masterful technique it used to do so. A series of questions and answers continued, in which the swordsman got involved, and the secrets of martial arts were told. The scroll the old cat is holding is not a book of secrets, referred to as “tora-no-maki” in Japanese meaning “tiger’s scroll”; rather, it is a “neko-no-maki,” or “cat’s scroll.”

The lending and borrowing of cats for mouse-catching

This is unrelated to the main subject of the fable, but the story unfolds under the presumption that borrowing cats to catch mice was customary. Such a relationship with neighbors must have been the norm. In fact, this practice is recorded in the diary of a court noble who lived in Kyoto during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s rule.

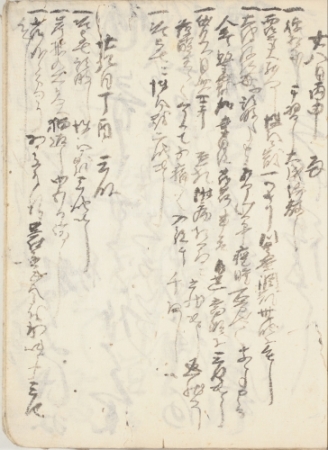

Picture 2 is Yamashina Tokitsune’s (1543-1611) handwritten diary. The passage from November 29th in the fourth year of Bunroku (1595), reads: “I returned the cat to Kishine Kyuemonnojo. I had borrowed it for 4, 5 days.” There is no information on Kishine, and the reason behind why Yamashina borrowed the cat is not clear from this passage alone. However, cats sometimes appear in Nishinotoin Tokiyoshi’s (1552-1639) diary “Tokiyoshi-ki” written around the same time. For instance, in the entry from intercalary August 3rd in the ninth year of Keicho (1604), there is a passage that reads, “Need a cat for mouse-catching; there’s a lot of mice,” which suggests that cats were used to catch mice, and they were loaned out for this purpose. Far from being so desperate as to “want even the help of a cat,” as a common Japanese expression goes, people at that time borrowed competent cats for mouse-catching.

The Tokiyoshi-ki entry dated October 4th in the seventh year of Keicho (1602), reads: “There was an order not to tether cats two, three months ago, and since then there have been instances of cats getting lost or getting mauled to death by dogs.” This rule is the opposite of saying “Don’t let your pets run loose.” From the fact that there had to be an order to make everyone let cats roam free, we can see that it was common practice to keep one’s cats tied up. In the scene in Wakana (Part I) of The Tale of Genji , the blinds are raised to give Kashiwagi a glimpse of Onna Sannomiya when a Chinese cat tied to the blinds pulls on its rope to escape. In “Ishiyamadera Engi Emaki” (Illustrated Legends of Ishiyamadera) from the 14th century, a cat tied to a rope is seen crouched near the doorway of a traditional Japanese house. Among the words used in haikai (Japanese linked verse), nekozuna – literally meaning “cat rope” – refers to someone who is disobedient and obstinate. Until around the 16th century, the custom of taking care of one’s cats by tying them up had been firmly rooted in society.

Picture 2: Passage from November 29th, Bunroku 4 (1595) in Yamashina Tokitsune’s “Tokitsune Kyoki” (Diary of Tokitsune). Owned by the Historiographical Institute

From tying cats up to letting them roam free

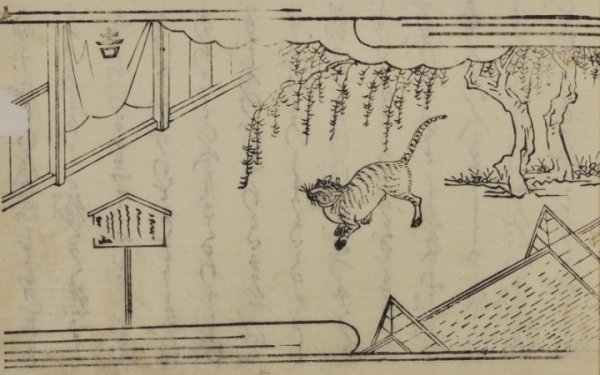

Picture 3: “Neko no Soshi” (Tale of the Cat) (Shibukawa edition of the Otogizoshi). Owned by the General Library (UTokyo)

Picture 3 is the first illustration in “Neko no Soshi” (Tale of the Cat), one of the stories in the Otogizoshi (The Companion Book) (Shibukawa edition; published in the early-Edo period (1700s)). The origin of the story is a bulletin board that was put up in Kyoto in mid-August in the seventh year of Keicho (1602) praising the peace of the Tokugawa period. “Cats inside the capital (Kyoto) should be untied and allowed to roam free. Similarly, the buying and selling of cats should be stopped.” Although it is unclear whether the text itself is accurate, it is certain that this kind of bulletin board was put up as it was also recorded in Tokiyoshi-ki. The cats rejoiced in their freedom; however, they got lost as they were not used to it – the owners therefore put name tags around their necks.

Prior to this, laws concerning cats had been put up in the town surrounding the Jurakudai palace in the 19th year of Tensho (1591) (Documents of the Mikumo Family). There were three articles prohibiting the stealing of cats, capturing of cats that came from elsewhere, and the buying and selling of cats. While there was no order to keep cats unrestrained, these prohibited actions are crimes that would occur only under the circumstance of cats being allowed to roam free.

Cats have been catching mice since ancient times. However, keeping cats unrestrained as a measure to prevent damage caused by mice reflects societal change in the way cats were viewed. In 16th-century cities, cats gained attention as animals beneficial to humans, and there was a trend among their owners to let them roam free. The ban on the stealing as well as the buying and selling of cats implies that with the sudden increase in the demand for cats, people started stealing others’ unrestrained cats and reselling them. Human hunting and trafficking accompanied the constant battles during the Sengoku period, and cats couldn’t escape this either. The Uesugi version of “Rakuchu Rakugai-zu Byobu” (painting on a folding screen of the views in and around the city of Kyoto) from the mid-16th century features a person luring and capturing dogs in the town. Under such circumstances, laws were necessary to lower the fear of losing one’s beloved cat and thereby encourage people to keep their cats unrestrained.

In the study of history, various time periods and events are addressed when discussing the relationship between the spontaneous tendencies of urban residents and the actions encouraged by rulers. Which carry more weight, and what kind of mutual dynamism can we assume from their relationship? The shift to “letting cats roam free” in the transition from the medieval period to the early-modern period was influenced not only by folk wisdom and the need for mutual aid; policymaking factors also played a large role.

“Shusui-zatsuwa,” a chorography book on the Wakasa Obama area of present-day Fukui Prefecture which was completed in the mid-18th century, quoted an order given in the 13th year of Kanei (1636) to keep cats unrestrained, and commented that “things are greatly different now.” The fading of memories after about a century would be hard to compare to “how quickly cats’ eyes change,” but aspects of our lifestyles, such as the way cats are kept, sometimes change completely, and social trends are an underlying cause of this. For more details, please refer to Hideo Kuroda’s Rekishi toshite no Otogizoshi (Otogizoshi as History) (Perikansha Publishing Inc., 1996), or my work (see picture 4).

Picture 4: Shigeo Fujiwara’s Shiryo toshite no Nekoe (Cat Paintings as Historical Material)

(Yamakawa Shuppansha, 2014)

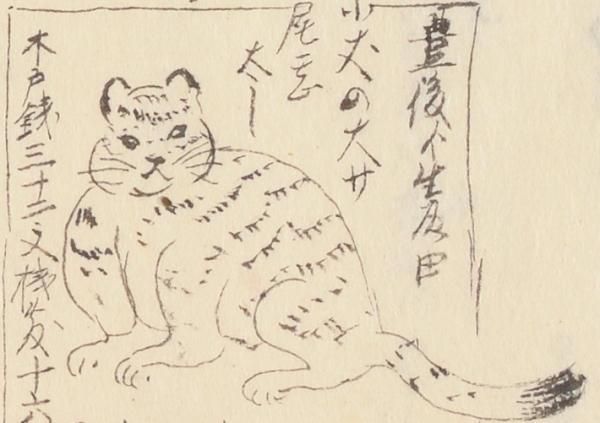

Passage from October 21st, Kaei 4 (1851) in the “Saito Gesshin Nikki” (Diary of Saito Gesshin). Owned by the Historiographical Institute

Passage from October 21st, Kaei 4 (1851) in the “Saito Gesshin Nikki” (Diary of Saito Gesshin). Owned by the Historiographical Institute

| This passage is about seeing a “tiger” that was made to perform as a part of a show in the vicinity of Ryogoku Bridge in present-day Tokyo. It is described as a type of cat rather than a tiger. According to “Fujioka-ya Nikki” (Diary of Fujioka-ya) (the original that was in the Imperial University’s library was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake), word spread that it was a rare animal that had been captured alive in Tsushima, an island off the coast of present-day Nagasaki Prefecture. The essay “Kiki no Manimani” (As I Heard It) says that musical instruments were played to mask the animal’s cries. It was likely a Tsushima leopard cat. |

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 37 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2018.