Beaming down support messages to the Games from space

Research, education and legacies related to the sporting event

The Olympic and Paralympic Games will be held in Tokyo for the first time in more than half a century. The University of Tokyo, which is also located in the metropolis, has a long history of involvement with the Games. As you learn about UTokyo’s contributions to this global sporting event, the blue used in the Olympic and Paralympic emblem may very well start to take on the light blue hue of the University’s school color.

| Space Engineering |

Beaming down support messages to the Games from space

From a nanosatellite carrying two Gundam figurines

On the roof of the Faculty of Engineering Building 7, where Professor Shinichi Nakasuka’s lab is located. The CubeSat XI-IV satellite, launched in 2003, is still operational and in orbit. This parabolic antenna was installed for the development of the Nano-JASMINE project. Photo: Takumi Inoue

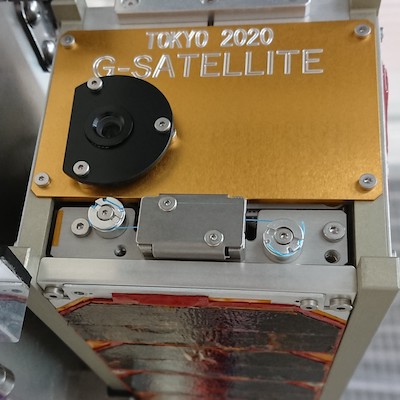

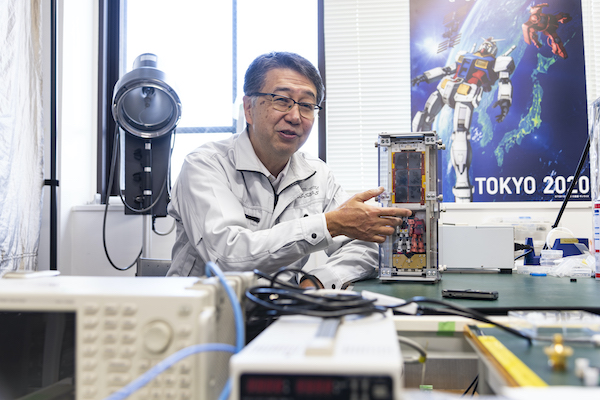

The G-Satellite to Space project is a world first. The project aims to load a nanosatellite with a pair of plastic figurines of characters from the popular science fiction anime Mobile Suit Gundam and an electronic bulletin board. The models will then send back messages during the Olympics and Paralympics to cheer on athletes from space. In charge of developing the satellite at the heart of this mission is Professor Shinichi Nakasuka, a pioneer in the development of micro/nanosatellites.

A satellite is generally considered “small” if it weighs less than about 500 kg. Micro/nanosatellites often weigh just 100 kg or less. Nakasuka’s lab has successfully launched 12 micro/nanosatellites, the first of them a tiny cube-shaped nanosatellite with a weight of just 1kg and size of 10 x 10 cm. In November 2019, a satellite jointly developed with the country of Rwanda was deployed from the Japanese Kibo lab on board the International Space Station. Given this experience, is it fair to assume that developing another microsatellite for the Olympics was just a walk in the park?

“You must be joking. Every satellite is different. Each project is quite different in almost every aspect: the intended use of the satellite, the team and the system for developing it, the specifications of the satellite, as well as the budget and deadline. Of course, experience is important, but as a developer, it’s a new experience every time. This project was no exception in that respect; we faced numerous challenges.”

One of the most significant difficulties was the short amount of time available. An advantage of micro/nanosatellites is that they can be developed over a relatively short period — but even so, it normally takes at least a year. This time, the satellite had to be produced in only around seven months. What persuaded Nakasuka to take on the project anyway? One factor was his affection for the Gundam series. He has been a fan since his second year as a university student, and says his favorite character is Sayla Mass. He has displayed a 1/144 scale Gundam figurine on a shelf in his lab since long before he became involved in this recent project. He had even planned a similar idea himself one time.

A second chance at a Gundam satellite

“Around 2005, I had the idea of launching a satellite inspired by the space colonies in the series. I built a detailed model of the colony cluster Side 7 from Gundam and proposed it to the production company. The people I spoke to were quite enthusiastic, but in the end the project never became a reality. Partly because of that, when the approach came from the Olympic Organizing Committee, there was no way I could refuse.”

A major satellite manufacturer chose not to get involved in the project, claiming it would take at least four years. Whether anyone reassured Nakasuka “You can do it!” (famous words of encouragement spoken by his favorite character in the series) is unclear, but the project got underway with his research lab playing a major role. The size of the satellite, determined by the budget and amount of time available for development, was 10 x 10 x 34 cm. The need to fit two models inside this box meant that the size of the Gundam figurines was reduced from the familiar 1/144 to a 1/200 scale. While the model manufacturer worked hard to find plastics and paints that could withstand an extraterrestrial environment, the laboratory and its partner company in Fukui Prefecture worked to design and implement the systems needed to control the two models from Earth once they had been placed in the satellite and blasted into space. After careful consideration, the team adopted what might seem a surprisingly primitive solution.

“We attached a spring to the base where the models are mounted and held it in place with fishing line, which is later burnt away using the heat from a nichrome wire. Why not use a motor? Actually, there are very few motors that work well in a vacuum environment. Motor problems have caused accidents and breakdowns in conventional satellites. We chose this method because it is the one we trust the best, having used it ever since our very first micro/nanosatellite.”

As their classification as “non-repairable systems” suggests, satellites cannot be fixed if anything goes wrong; once they are in space, no one can reach them to carry out repairs. With larger satellites, it is possible to equip the satellite with backup systems that can help to address any problems that might arise, but on micro/nanosatellites, the limitations of size and cost make this impossible. All the designers can do is to do their best under the given conditions. To mitigate against possible failure, one of the seven cameras on the satellite will be used exclusively for taking footage of the Gundam figurines in their moored state.

Create a die-hard satellite!

“The most important thing is to ensure that whatever happens, you don’t lose functionality entirely. I’m always saying to my students: ‘Your aim should be to create a die-hard type of satellite!’”

The last time the Olympics were held in Tokyo, Nakasuka was three years old. He remembers being excited by the sight of Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian gold medalist in the marathon, and running around shouting: “Abebe! Abebe!” This time, the Olympics will be a period of continuous stress and hard work, as he hurries to launch the rocket, deploy the satellite from the space station, blast the Gundam figurines into space, display the support messages on the board, illuminate the five-colored LEDs embedded in their eyes, rotate their necks, and conduct a special event of listening in on conversations between the Gundam characters Amuro and Char. Although he might feel a thrill once the satellite is working as planned, he won’t be running around with excitement this time while watching the Olympic Games.

“I’ve always loved sports. I founded a tennis club in high school, and when I was in university, my team came in third in the President’s Cup for baseball. This time, I’m particularly looking forward to watching the baseball events, back in the Olympics for the first time after a long absence, and the men’s and women’s gymnastics.”

As well as leading the day-to-day work of developing satellites, Nakasuka is also a member of the Japanese Cabinet Office’s Committee on National Space Policy. One of the subjects discussed at the committee is the future of Japan’s space development, and this is another reason why Nakasuka decided to get involved in the current project.

“In the past, I think there was a tendency to focus on the technological side of developing satellites, but in the future it will be necessary to think carefully about how we want to use satellites as well. It used to be that computers were something only a limited number of people used, but the advent of the personal computer lowered the threshold and gave rise to new ways of using them. This led to massive new development. I think the same thing is likely to be true of space development, and one of the most promising areas for this new technology is entertainment. The Gundam satellite will be a good example of this.”

One year later. After completing its mission, the plan is for the Gundam satellite to burn up on reentering the atmosphere — but Nakasuka’s energy and drive to bring space development into new dimensions shows no signs of burning out any time soon.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 40 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2020.