Tackling global climate crisis The Center for Global Commons marks one-year anniversary, pulls resources together to build sustainable socioeconomic systems

© Anton Balazh / Adobe stock

From extreme weather and desertification to loss of biodiversity, human economic activity has been taking a toll on the global environment. Scientists warn that we have only 10 years left to find a sustainable path; otherwise, they say, we would lose control. In a bid to contribute to the global efforts of addressing this crisis, in August 2020, the University of Tokyo launched the Center for Global Commons (CGC). One year on, we caught up with UTokyo Executive Vice President and CGC Director Naoko Ishii who talked about the center’s mission, and its ongoing and upcoming projects.

―― How did the CGC come about?

The starting point was the sense of crisis that if we continue with the way we have been developing our economy, we will end up destroying the global environment itself that supports our economy. People had long taken for granted that the Earth is vast and wide, and despite human activity, its environment could not be damaged beyond repair. But recently, the power of human impact has become so strong that the Earth’s capacity is reaching a tipping point, to the extent of threatening the planet’s stability. We must recognize that first. Therefore, in order to change this predicament, it’s crucial to transform our socioeconomic systems. The CGC was established to figure out ways to realize that transformation.

―― What exactly are the “global commons”?

The term refers to the stable and resilient Earth system that sustains our lives (comprising components such as biodiversity, climate, forests, oceans and land, as well as the various physical movements and energy flows they encompass). The CGC started by asking how we can create a mechanism to protect the global commons together.

―― How will the CGC tackle the issues?

The first thing is to come up with a framework to responsibly manage the global commons, then at the same time to start implementing it.

There are several important components for building such a framework. But, I believe its key pillar would be modeling transformation of socioeconomic systems. That means, we need to find ways to change various systems, such as looking at how food systems should be transformed, in addition to decarbonizing the energy sector and other areas, and improving the circularity of life in cities and entire economic systems.

Our goal is to figure out ways to achieve sustainable economic growth in 2050 without crossing the planetary boundaries (limits on Earth processes tied to human activity, such as freshwater use, land-system change and ocean acidification, for humanity to safely operate on the planet). This is a huge task.

―― The center is collaborating with various types of organizations. Is there a particular role a university can play?

There are many people who believe in the need to protect the global commons, including players in industry, researchers, people from civic groups and policymakers. The question is who can play a secretariat role to bring together these people from different sectors and create a collaborative relationship.

In Japan, it is often difficult to have cross-sectional cooperation as the structure of society is divided vertically. But by making good use of the distinct qualities of a university, such as its relatively neutral position, built-in trust and intangible academic assets, we thought we could create a collaborative relationship that would bring together people from industry, academia and civil society.

―― Can you tell us about the joint research between the CGC and Mitsubishi Chemical Corp. (MCC) announced in April, and the center’s collaboration with Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) introduced in June?

The theme of the joint research with MCC is to seriously consider the role of the chemical industry in bringing about a sustainable society. For example, in the case of MCC, the company is using naphtha (crude gasoline) to make plastics. It’s important for the basic materials industry to shift its focus and think about making its products sustainable for the people who use them. We are aiming to conduct research on ways to achieve this.

The actions of the financial sector, which has a significant influence over the entire economy and industry, are critical to solve the global environmental issues. By starting a collaboration with MUFG, one of the largest financial groups in Japan, CGC now has more power to drive socioeconomic changes, including the decarbonization of Japan.

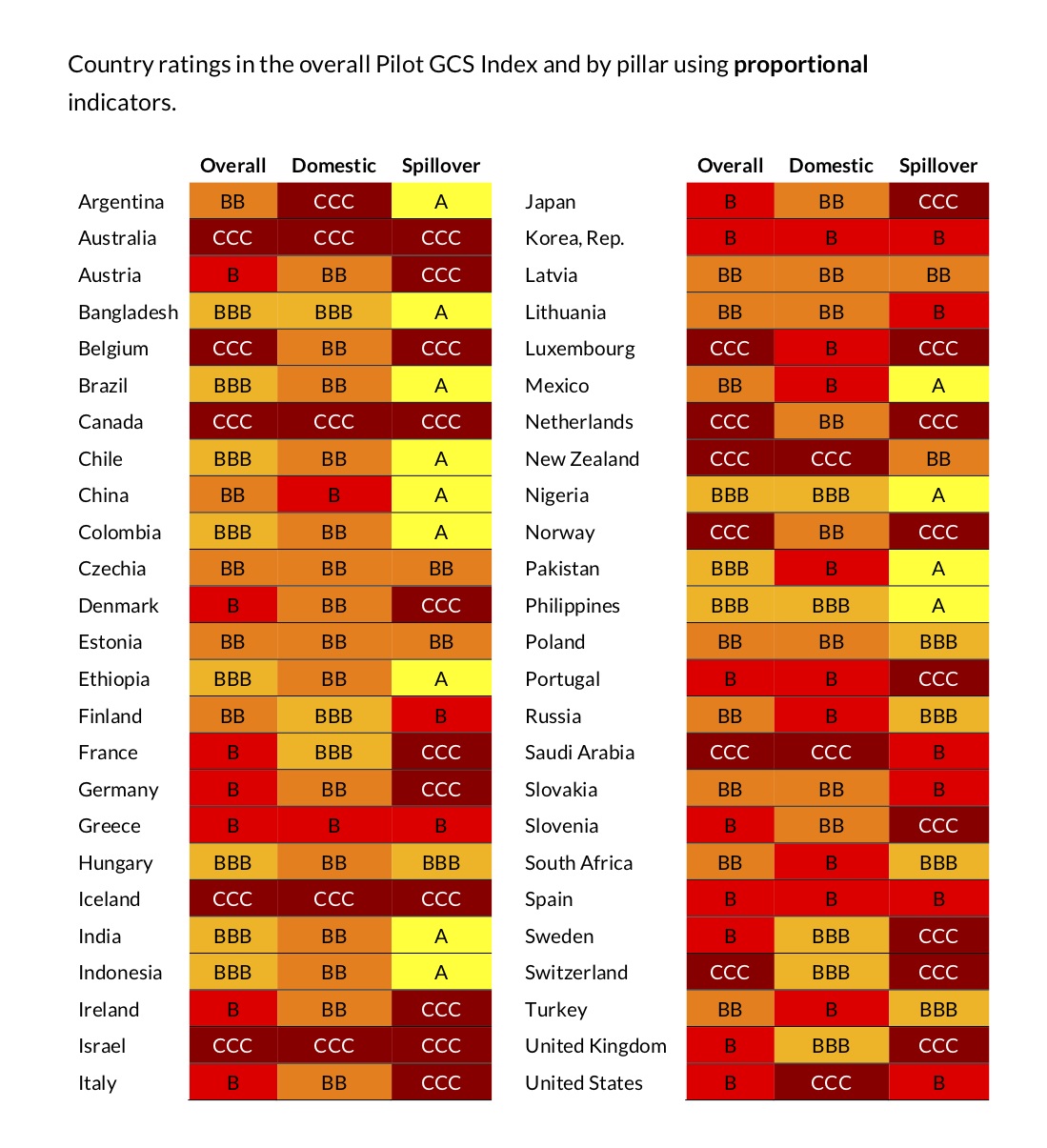

SDSN, Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, and Center for Global Commons at the University of Tokyo. 2020. Pilot Global Commons Stewardship Index. Paris; New Haven, CT; and Tokyo.

―― CGC released a pilot version of the Global Commons Stewardship Index (GCSi) in December 2020. What does it tell us?

This index measures a country’s positive contribution or negative impact on the six global commons components, including climate change, biodiversity and oceans. For the pilot version, we presented the results of 50 countries for which data was readily available — members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the G-20 (industrial and emerging-market nations) and five countries with the largest populations. We presented the data in the form of a report card.

After all, it would be great if our activities spark discussion among countries, to educate and enlighten each other, or to learn from one another. Also, I hope the index could serve as a guide to help investors determine sectors in different countries that are easy to invest in.

We’re planning to publish the GCSi every year. For this year, we are working to improve the index, and aiming to release it by the Tokyo Forum likely to be held again in December.

―― What’s your plan on education?

We are currently discussing to create an educational program on the global commons and also ways to make it into a proper curriculum with faculty members at the Institute for Future Initiatives who share similar ideas, and faculty who have been studying sustainability. We would like to launch the program as soon as possible, and we are in the process of creating content for a course that will be offered to first-year undergraduate students.

―― What difficulties have you faced over the past year?

It's a huge challenge to figure out how to steward the global commons and I didn't think it would be easy. So, everything has been within my expectations.

I think we have been very lucky, though, in that the time is ripe (to address the global commons as the issues have become quite topical). We’ve been hearing the message that “we have only 10 years left,” more strongly and loudly around the world. In 2020, Japan pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. To reach the goal, Japan also announced to cut its carbon dioxide emissions in half by 2030. Given such growing momentum, more people are starting to look for places where they can contribute. I feel that’s where the CGC can be of help and more people are finding value in what we do.

That being said, the CGC is still not widely known. I believe we need to show some results to raise our profile. We are just getting started.

―― Can you tell us about some upcoming projects?

We are working on the GCSi project with institutions such as the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (in Germany) and the U.N. Sustainable Development Solutions Network, and we are also working with the World Resources Institute (based in the U.S.) to implement “system transformation” (to build sustainable societies). We hope to compile these ongoing projects and publish a framework on global commons stewardship by this fall, before the COP 26 (U.N. climate change conference), which will be held in Glasgow in November. I hope these projects would spark active discussion at December’s Tokyo Forum.