Russia’s assault on Ukraine and the international order Conflict against the backdrop of NATO expansion and secession disputes

As Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine continues, fighting has been raging in the Donbas region in the eastern part of the country. UTokyo Professor Kimitaka Matsuzato of the Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, who has been studying Ukrainian politics and has visited the country over the years, went to the Donbas in 2014 and in 2017. When he visited the region in the summer of 2014 — the time when fighting between Russian-backed rebels (having declared themselves the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic) and the Ukrainian army intensified — he said bullets landed near his hotel. Recalling the time just before Russia launched its recent assault on Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, Matsuzato said: “I thought Russia might recognize the two breakaway republics of the Donbas, but I was not expecting it would launch a war on the whole country.” We caught up with Matsuzato, who is an expert on the history of the Russian Empire and post-communist politics, to learn about the background of the military aggression, including territorial issues and NATO’s eastward expansion.

© harvepino / Adobe stock

Issues in the Donbas stuck in a dead end

―― What kind of region is the Donbas? Why has Russia backed the secessionists there?

Russian policy toward the conflict in the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine has changed over time.

Today, the Donbas region refers to two oblasts (provinces), Donetsk and Luhansk. These two regions were established in the 1920s and 1930s as part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. It was and continues to be a predominantly Russian-speaking region. When the Euromaidan protests (an uprising that overthrew President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014) took place, radicals rebelling against the uprising occupied the regional government buildings in the two regions. Proclaiming themselves the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), they held a referendum on the regions’ independence from Ukraine. This eventually led to war with Ukraine, and by 2015, the Minsk II agreement had drawn military borders and the republics had taken effective control of roughly one-third of the two regions.

In 2015, Ukrainian, Russian, OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe), and DPR/LPR representatives signed the Minsk II agreement, which aimed to reincorporate the two breakaway republics into Ukraine by turning Ukraine into a federal state. This, however, was not an attractive solution for either Ukraine, which was reluctant to federalize itself, or the breakaway republics, which sought complete independence from Ukraine.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s policy toward the Donbas conflict can be broken into three stages — up to August 2014, between August 2014 and 2019, and thereafter. From the spring of 2014 when the war broke out in the Donbas to up until August the same year, the Russian presidential office was ambivalent toward the secessionist movement in eastern Ukraine. The reasons were, firstly, it was a fringe movement instigated by a marginal class and the Putin regime did not see a need to support it, unlike the secessionist movement in Crimea, which developed in close liaison with the Russian presidential office. Secondly, as the name “people’s republic” suggests, the secessionist movement in the Donbas took on the nature of a social revolution with anti-capitalist and anti-oligarchic tendencies. And that was not acceptable for the right-leaning, conservative Putin.

Thirdly, since the Russian regime generally sees no point in propping a foreign political entity that lacks the ability to survive on its own, I believe it was waiting to see whether the secessionists in the Donbas would survive or not. This was indeed the case in the War in Abkhazia in 1992 and the Second South Ossetian War in 2008 (also referred to as the Russo-Georgian War, implying Georgia’s failed attempt to reintegrate South Ossetia militarily), and the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War (Azerbaijan’s successful attempt to reintegrate Karabakh militarily), where Russia made up its mind to intervene only after assessing the breakaway regions’ survivability.

©2022 Kimitaka Matsuzato

Around August 2014, after the Ukrainian military began full-scale bombing and shelling of the Donbas, while incidents such as the alleged downing by Donbas paramilitaries of a Malaysian airliner over eastern Ukraine had also occurred, the Putin regime could no longer afford to just sit idly by observing the conflict. So, it began supporting the DPR/LPR after demanding they agree to three conditions: First, purge the radical element that had led the DPR — LPR leaders were more moderate and suffered a purge to a lesser extent; second, end the social revolution; and third, agree to return to Ukraine in the long term. As the DPR/LPR accepted these conditions, Russia began to support them and this situation continued until around 2019. (For more information on this process, refer to the chapter “The First Four Years of the Donetsk People’s Republic: The Differentiating Elites and Surkov’s Political Technologists,” authored by me in The War in Ukraine’s Donbas: Origins, Contexts, and the Future [David Marples, ed., Budapest: CEU Press, 2022]).

Putin adopted this relatively moderate policy as he was aiming to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO by pushing the rebel-controlled regions, which hold a large-number of pro-Russia votes, back into Ukraine.

During the third period, after conceding Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s victory in the presidential election in April 2019, the Putin regime gave up the idea of changing Ukrainian politics from inside the country. Instead, it began readily granting Russian citizenship to residents of the DPR/LPR. This was a dangerous sign, signaling Putin’s waning interest in reincorporating these regions into Ukraine. According to an article published in The Wall Street Journal on April 1, 2022, Putin’s mind was made up to wage war against Ukraine after Zelenskyy told the Russian leader that he was not very willing to go forward with the Minsk II accord, when the two met in Paris in December 2019 during peace talks over the conflict in the Donbas region among the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, Germany and France.

The risks of using NATO as a populist slogan

―― Do you think Putin upheld preventing Ukraine from joining NATO as an objective of the war?

Absolutely. Putin sought assurances from the U.S. that Ukraine would not join NATO, but when the U.S. did not consent, he used that as an excuse for invading Ukraine.

In the past, there were countries such as Austria during the Cold War that were prevented from joining NATO, not due to their own will but because of an international treaty (Austrian State Treaty of 1955 in Austria’s case). The current open-door policy, allowing any European country to join if all member states unanimously approve, was adopted at the 1997 NATO Summit in Madrid, and is a separate issue from respect for national sovereignty under international law.

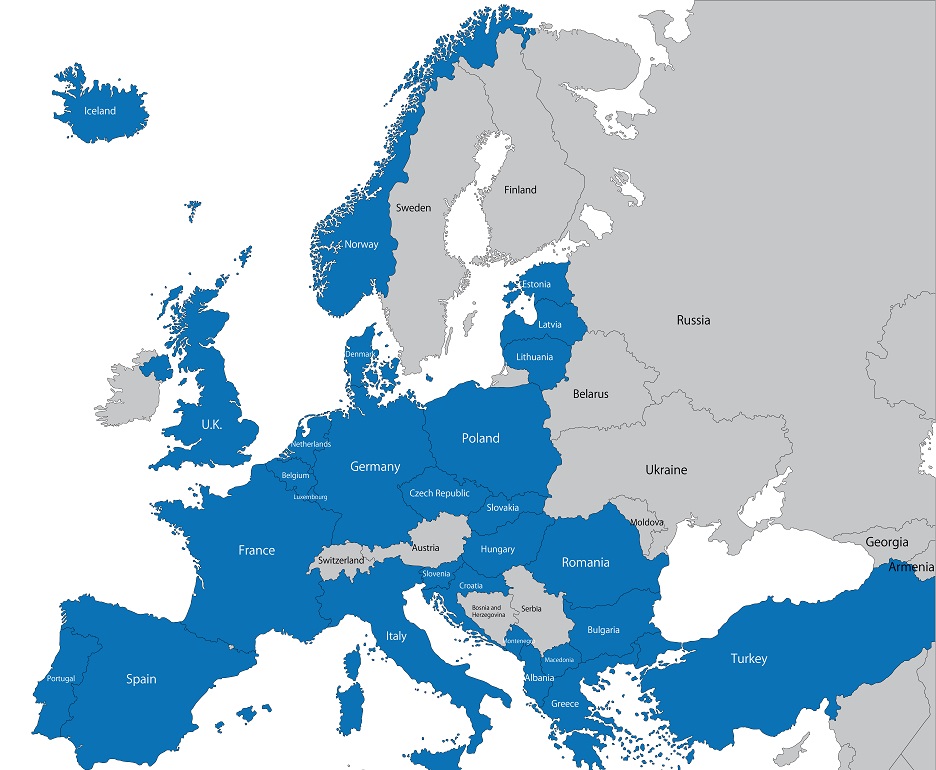

So far, NATO has expanded eastward, with Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary joining in 1999, and seven other Eastern European countries in 2004. Furthermore, at NATO’s Bucharest Summit held in April 2008, member states reached an agreement to invite Ukraine and Georgia to join NATO in the future. But as the Second South Ossetian War and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 made clear, the Russian leadership’s fixation with Georgia and Ukraine is much stronger than that of its attachment to the three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) and Romania and Bulgaria, and NATO’s eastward expansion has slowed down.

The Putin regime’s aversion toward the expansion of NATO grew even stronger from 2018 when the major powers started full-fledged efforts to develop supersonic missiles. If, for instance, Ukraine joins NATO and supersonic missiles are deployed in Kharkiv (in northeast Ukraine), the missiles are said to have the capability of reaching Moscow within 5 minutes. However, the more dire the military consequences of NATO expansion, the greater the role the NATO issue plays in mobilizing the populist vote in elections.

It is clear that the aforementioned rash agreement at the Bucharest Summit was reached against the backdrop of then-U.S. Republican presidential candidate John McCain struggling in the runup to the U.S. election, and then-Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili and then-Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko seeing their popularity plummet. McCain took a hard-line stance against Russia to gain popularity, while Saakashvili and Yushchenko wanted to gain domestic support by showing their country would soon be recognized as a member of the West.

Ukraine’s constitutional amendment in 2019 to make NATO membership a constitutional provision was a desperate attempt by then-President Petro Poroshenko to overturn Zelenskyy’s dominance in the upcoming presidential election. Later, Zelenskyy also began to push strongly for NATO member states to expedite Ukraine’s admission to the alliance as his approval rating started to decline. Thus, the military issue of NATO has been used as a means to win elections in various countries.

So, why couldn’t the Western countries, which had no intention of letting Ukraine join NATO in the first place, make a treaty stipulating that Ukraine will not be admitted into NATO, as they had done with Austria? That would have eliminated one of Putin’s pretexts to launch the current war against Ukraine. This point was raised by many scholars and journalists in the leadup to Russia’s military aggression. I believe that either the leaders of the NATO member states were afraid of being criticized in their country for being weak-kneed against Russia or they wanted to support the Zelenskyy administration whose approval rating was falling.

Putin challenges international rules

―― How do you see the impact of the invasion on the international community?

The biggest lesson this war has taught us is that the international community should not disregard secession conflicts (in this case, the Donbas conflict). If it does, as was the case in the 2008 South Ossetian War and the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, the military conflict will tend to relapse with a much larger scale of casualties. In the current international system, we only have a method to mediate conflict by mutual agreement. But the problem is when that is difficult, we don’t have a system to resolve the matter through arbitration. I think we should create an international judicial system that resolves secession disputes through arbitration, as well as introduce a system to punish countries that avoid settling disputes within a set time frame.

Currently, the international community is divided into two groups: Europe, the United States and Japan on the one hand, which strongly denounce Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, and on the other hand those that do not condemn Russia, such as China, India and the Middle Eastern countries. Diplomacy between the two sides is at loggerheads, but if the two groups can sit down together and discuss the reasons for their differences, I believe we may gain some clues about our future international order.

Kimitaka Matsuzato

Professor, Graduate Schools for Law and Politics

Completed doctoral program in the Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, Doctor of Laws. Served as professor at the Slavic Research Center (current Slavic-Eurasian Research Center), Hokkaido University. In current position since 2014. Matsuzato has published the following essays on the Ukrainian crisis since 2014: “Domestic Politics in Crimea, 2009-2015,” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 24, 2 (2016); “The Donbass War: Outbreak and Deadlock,” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 25, 2 (2017); “The Donbass War and Politics in Cities on the Front: Mariupol and Kramatorsk,” Nationalities Papers 46, 6 (2018). Readers may also refer to Russia and Its Northeast Asian Neighbors: China, Japan, and Korea. 1858-1945 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017) edited by him.