The unknown reasons why Hollywood films were imported to South Korea via Japan

| Film Policy Studies |

The unknown reasons why Hollywood films were imported to South Korea via Japan

Book written by Assistant Professor Chung:

Book written by Assistant Professor Chung:

Nikkan Indipendento Eiga no Keisei to Hatten: Eiga Sangyo ni taisuru Seifu no Kainyu

[The Formation and Development of Japanese and Korean Independent Cinema: Government intervention in the film industry] (Serica Syobo, 2017)

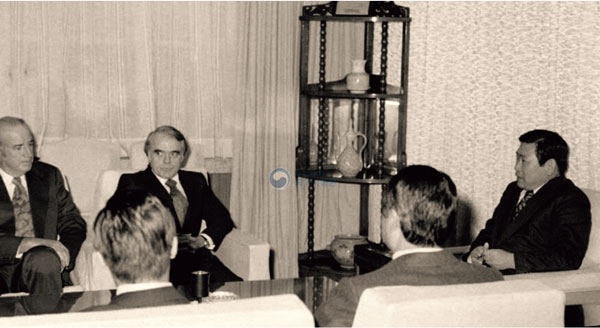

Jack Valenti, president of the MPAA, meets with the South Korean Minister of Culture in 1976 to discuss the establishment of a Far Eastern office.

Source: National Archives of Korea

Despite the recent spotlight on K-content – meaning entertainment products originating from South Korea, such as the television series Squid Game and the Oscar-winning film Parasite – the South Korean film industry was actually extremely small until the mid-1990s. The film market was opened in the latter half of the 1980s. Prior to that, the film industry was tightly controlled by the government, which determined the number of films that could be imported as well as the suppliers, among other matters. Perhaps because of the small size and opacity of the market, direct imports of Hollywood films were almost impossible. There are a few testimonies from filmmakers who were involved in importing in the 1960s and 70s who say that they went to Japan because Hollywood would not deal with them, and because that was where Hollywood’s Far Eastern branch was located. It seems that until the mid-1980s, most American films that screened in South Korea were imported by way of Japan.

This gives rise to various questions. What led them to bring American films from Japan? Who did the suppliers deal with? Were the transactions official? How much authority did the Hollywood studios extend to their Far Eastern branch? The journey in search of answers is not an easy one. Even after sifting through the oral history materials collected from former senior filmmakers at the Korean Film Archive, I found no evidence indicating any involvement with the Japanese (Far Eastern) branch. But one thing that did come up frequently was the existence of Zainichi brokers residing in Japan who relayed the sale of American films. A newspaper article from 1974 reports a legal dispute that arose between two vendors that each signed a contract with the branch office in Tokyo and a Tokyo-based foreign film distributor for the distribution rights to the American film Samson and Delilah. The article suggests the possibility that some transactions via brokers may have been unofficial. Nevertheless, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) was aware of their existence. In 1976, the president of the MPAA visited South Korea and expressed his desire to establish a joint branch office of the major Hollywood studios to prevent profiteering by brokers, but this was not possible in South Korea, which at that time had a centrally planned economic system.

Japanese influence in South Korean society had continued after South Korea gained independence in 1945, as the process of importing American films reveals. While the U.S. was a far-off place in terms of geography, language and personal connections, Japan was close in every respect. When considering that a sizeable number of importers at the time were either born or educated in Japan during the colonial period, the fact that they turned towards Japan was not unrelated to their colonial experience. Decisions on what foreign films to import were highly influenced by the their box office performances in Japan, and posters and flyers made as Japanese promotional materials were used more or less as is, with only the text replaced with Korean.

Late last year, I conducted an interview with Toshio Furusawa, a long-time employee of the Japanese branch of 20th Century Fox since the 1960s. He had not been aware that the poster for the Japanese version of Star Wars, which he had been in charge of, was used as is in South Korea. However, he said that even if he had known, he would not have cared so long as it resulted in positive sales for the head office.

This research is also an exploration of how people who lived locally at that time came to terms with globalization, intertwined with the international situation and colonialism in East Asia as it existed after the 1950s, as well as diaspora issues. I enjoy the process of putting together the scattered pieces of this puzzle.

| Year | Number of domestic films | Number of imported films | Number of directly distributed Hollywood films | Proportion of domestic production (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 81 | 25 | 0 | 76.4 |

| 1985 | 80 | 27 | 0 | 74.8 |

| 1986 | 73 | 50 | 0 | 59.3 |

| 1987 | 89 | 84 | 0 | 51.4 |

| 1988 | 87 | 175 | 1 | 33.2 |

| 1989 | 110 | 264 | 15 | 29.4 |

| 1990 | 111 | 276 | 47 | 28.7 |

| 1991 | 121 | 256 | 45 | 32.1 |

| 1992 | 96 | 319 | 57 | 23.1 |

| 1993 | 63 | 347 | 64 | 15.4 |

Source: Korean Film Council (2000), Korean Film Yearbook

The South Korean film market was opened in 1988. Despite the vehement protests of domestic filmmakers, major Hollywood studios established a South Korean branch of United International Pictures (UIP) as a joint venture for distributing films directly to South Korean movie theaters.

* Assistant Professor Chung’s affiliation and title are as of March 2022.

** This article was originally printed in Tansei 44 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2022.

By Insun Chung

By Insun Chung