Why is the order of the Japanese syllabary “a-i-u-e-o/a-ka-sa-ta-na?”

An introduction to academia starting with “Why?”

After making a list of questions which would pique anyone’s interest, we asked faculty members on campus who might be knowledgeable in these areas to answer them from the perspective of their respective expertise. Let’s take a look into the world of research through questions that you feel you know something about, but cannot answer definitively when actually asked.

Q7. Why is the order of the Japanese syllabary “a-i-u-e-o/a-ka-sa-ta-na?”

Why does the order of the Japanese syllabary have to be “a-i-u-e-o” in the first place? Wasn’t “i-ro-ha-ni-ho-he-to” also used in the past?Monks devise ways to correctly recite incantations

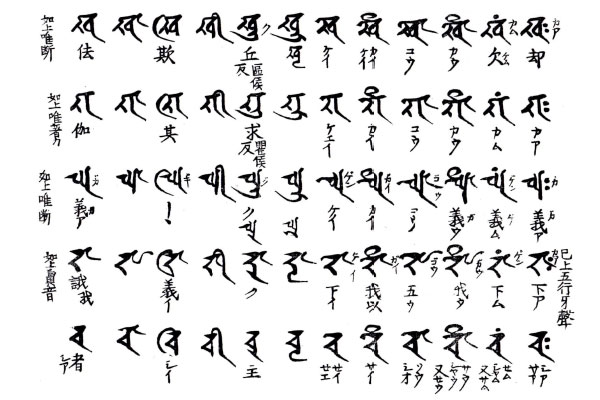

The sequential order in the column for “a-i-u-e-o” and the sequential order in the row for “a-ka-sa-ta-na-ha-ma-ya-ra-wa” are based on the Sanskrit alphabet table from India. Esoteric Buddhist monks diligently studied Indian script to correctly chant mantra-dharani and other incantations in Sanskrit. The pronunciation of Sanskrit was complex with more than 7,000 characters, and the original script charts were lengthy. The Japanese syllabary chart was assembled by simplifying these charts to fit the Japanese language.

Vowels are placed at the beginning of the Sanskrit alphabet table. First are the basic vowels “a,” “ā,” “i,” “ī,” “u” and “ū,” followed by the secondary vowels “e,” “ai,” “o” and “au.” (Simpler descriptions are used hereafter.) Picking out what can be written with a single Japanese kana character, you get the order of “a,” “i,” “u,” “e” and “o.” In the second and subsequent columns, the letters are arranged by adding a consonant before the vowel. The first consonant is k, and hence the second column contains “ka,” “kā,” “ki,” “kī,” “ku,” “kū,” “ke,” “kai,” “ko” and “kau” in the sequence, converting to “ka,” “ki,” “ku,” “ke” and “ko” in Japanese. In the same way, more than 30 consonants are combined with the vowels, which is the first chapter of the alphabet table.

Consonants are divided into two main groups. First are the strong consonants (plosives, affricates and nasals), which are arranged in order of position of articulation starting with consonants, with the position at the back of the mouth. Among those with the same position of articulation, nasals are last. In Japanese, we have “ka,” “sa,” “ta,” “na,” “ha” and “ma” (the differentiation between voiceless and voiced sounds is omitted). Next, among the weak consonants (approximants and fricatives), the approximants (semivowels), arranged according to the articulation position from the back to front of the mouth, are transferred to Japanese as “ya,” “ra,” and “wa.” In this way, the order of “a,” “i,” “u,” “e” and “o” / “a,” “ka,” “sa,” “ta,” “na,” “ha,” “ma,” “ya,” “ra” and “wa” was created.

However, the Japanese syllabary has not always been in its present form. The oldest existing syllabary (circa A.D 1000) is in the order of “i,” “o,” “a,” “e” and “u.” The second oldest syllabary has two varieties: “a,” “i,” “u,” “e,” and “o” order and “a,” “e,” “o,” “u” and “i” order. The latter order seems to have become somewhat popular, and examples can be found in books on poetry from the Heian period. From the beginning, the order in the row did not have to be arranged in any particular manner. Even much later, various arrangements were used depending on the purpose. Phonetically organized dictionaries up to the Edo period generally used the “iroha order” rather than the fifty syllables in the “a-i-u-e-o order,” precisely because of the fluidity of the latter.

I have been studying the phonological history of Japanese, starting with the Siddham studies on Sanskrit and moving on to the Japanese pronunciation of kanji and pronunciation of native Japanese words. Recently, my interest lies in the issue of inserting choked sounds, which sometimes behave as mirror images of voiced sounds, such as with “migigawa/migikkawa” and “kawaberi/kawapperi.” Compared to voiced sounds, for which a vast amount of research has been accumulated, the historical facts and actual situation in modern languages have not been fully elucidated for choked sounds. I believe that further research on choked sounds will provide new insights also into voiced sounds.

Nihongo Arekore Jiten (“Dictionary of This and That in the Japanese Language”) (Meiji Shoin, 2004)

This book answers various questions about the Japanese language. In addition to a discussion of the Japanese syllabary, Professor Hizume also explains the use of “di” and “ji” in Japanese.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 45 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2022.

Answered by Shuji Hizume

Answered by Shuji Hizume