Why doesn’t every country in the world become a democratic state?

An introduction to academia starting with “Why?”

After making a list of questions which would pique anyone’s interest, we asked faculty members on campus who might be knowledgeable in these areas to answer them from the perspective of their respective expertise. Let’s take a look into the world of research through questions that you feel you know something about, but cannot answer definitively when actually asked.

Q10. Why doesn’t every country in the world become a democratic state?

To those who have been taught that democracy is the best system of government, it seems strange that there are not that many democratic countries across the world. Isn’t democracy the best option?Only thirty percent of the world’s population live in democratic countries

Democratic government in its original sense requires adequate guarantees on individual freedoms and widespread political participation among its citizens. According to a report published by the V-Dem Institute in Sweden, democratic countries in this sense are in the minority, accounting for only 30% of the world’s population. In recent years there have even been cases of countries stepping back from this form of government.

Here, I would like to refer to a famous quote from former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: “It has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” In what sense is democratic government the “worst”?

In reality, for most of human history, democratic government has not had a particularly positive image. In his book Politics, Aristotle proposed six types of government, based on the number of rulers (the one/the few/the many) and the goals (for the rulers/for the common interest). Democratic government is the type that involves rule by the many, for the rulers, and Aristotle places this system in the B class, ranked fourth in terms of its merits.

The systems included in the A class, considered better than democratic government, are those in which the rulers govern in the common interest, which are in order of preference: monarchy, aristocracy and polity. Monarchy, which ranks first, could be seen as something like the regimes that existed under ancient Chinese emperors such as Yao and Shun as described in the Records of the Grand Historian. A system in which a single “benevolent ruler” makes swift decisions certainly seems more efficient than the long and fruitless debates that characterize democratic government.

No better system than democratic government

http://www.masaki.j.u-tokyo.ac.jp/utas/utasindex.html

Emperors such as Yao and Shun, however, are no more than figures of legend. There are no real-life examples of an individual or small group of leaders ruling solely in the interests of all the people they rule. Moreover, once a dictator or minority elite begins to rule in their own interests, it becomes the worst possible form of government. To imagine such a scenario, you need only call to mind figures such as Hitler and Stalin. There may be a more desirable system of government in theory, but in actual fact, the only types of government seen in human history thus far are democratic government, and systems that are worse than it. This is what Churchill meant in his words that I mentioned earlier.

Democratic government cannot be considered the “best” system of government that is theoretically possible, but it is the “least bad” among those systems that actually exist. Nonetheless, some people are still convinced that it will be possible to find a better system than democratic government, and others advocate for such a possibility despite knowing it to be false. That is the answer to the question above.

In the aforementioned V-Dem ranking of democratic governments, Japan performs reasonably well, in 28th place out of 179 countries. But there is no goal line for democratic government. Trends such as populism and mistrust of politics are clearly on the rise in many developed countries today, and Japan also faces a host of intractable problems such as ballooning public debt and population decline owing to aging and low birthrate. In my research, I’m constantly exploring better models for political institutions such as parliaments and political parties, and for political communication among people, in order to maintain a healthy democratic government that doesn’t buckle under these compounding problems.

| 1 |  Sweden Sweden |

0.88 |

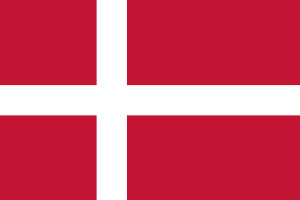

| 2 |  Denmark Denmark |

0.88 |

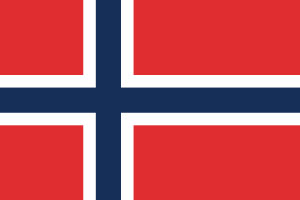

| 3 |  Norway Norway |

0.86 |

| 4 |  Costa Rica Costa Rica |

0.85 |

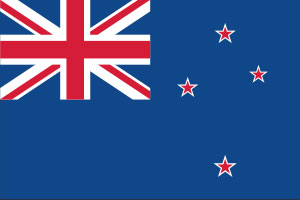

| 5 |  New Zealand New Zealand |

0.84 |

| 6 |  Estonia Estonia |

0.84 |

| 7 |  Switzerland Switzerland |

0.84 |

| 8 |  Finland Finland |

0.83 |

| 9 |  Germany Germany |

0.82 |

| 10 |  Ireland Ireland |

0.82 |

| 11 |  Belgium Belgium |

0.82 |

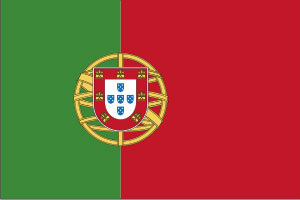

| 12 |  Portugal Portugal |

0.81 |

| 13 |  Netherlands Netherlands |

0.81 |

| 14 |  Australia Australia |

0.81 |

| 15 |  Luxembourg Luxembourg |

0.8 |

| 16 |  France France |

0.79 |

| 17 |  South Korea South Korea |

0.79 |

| 18 |  Spain Spain |

0.78 |

| 19 |  United Kingdom United Kingdom |

0.78 |

| 20 |  Italy Italy |

0.77 |

| 21 |  Chile Chile |

0.77 |

| 22 |  Slovakia Slovakia |

0.77 |

| 23 |  Uruguay Uruguay |

0.76 |

| 24 |  Canada Canada |

0.75 |

| 25 |  Iceland Iceland |

0.75 |

| 26 |  Austria Austria |

0.75 |

| 27 |  Lithuania Lithuania |

0.74 |

| 28 |  Japan Japan |

0.74 |

| 29 |  United States United States |

0.74 |

| 30 |  Latvia Latvia |

0.73 |

Extracted from rankings produced annually by the V-Dem Institute, headquartered in the University of Gothenburg, based on more than 470 indicators. Other rankings of the same type include the UK’s The Economist ranking, the 2021 edition of which ranked Japan 17th (Norway took first place).

Gendai Nihon no Daihyosei Minshu Seiji (“Representative Democracy in Japan”)

(University of Tokyo Press, 2020)

This book provides a cross-sectional comparison of the policy positions of both voters and politicians, drawing on survey data collected from both groups.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 45 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2022.

Answered by Masaki Taniguchi

Answered by Masaki Taniguchi