Why is modern art so perplexing?

An introduction to academia starting with “Why?”

After making a list of questions which would pique anyone’s interest, we asked faculty members on campus who might be knowledgeable in these areas to answer them from the perspective of their respective expertise. Let’s take a look into the world of research through questions that you feel you know something about, but cannot answer definitively when actually asked.

Q19. Why is modern art so perplexing?

Lines that look like scribbling, daubs of paint everywhere, a plain old toilet… Why is modern art so difficult to understand? Is it deliberate?Duchamp’s transformative impact on the concept of art

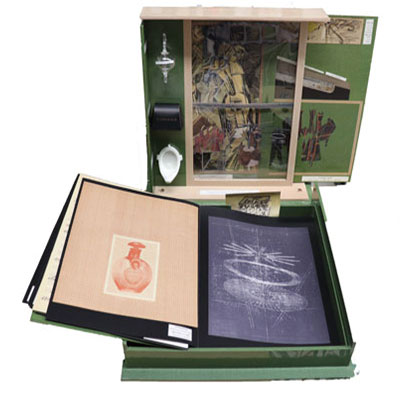

Resembling a toybox, this work is filled with miniature versions of 69 different artworks by Duchamp, including The Large Glass, Beautiful Breath and Fountain. It was sold (as a book) under the supervision of another modern artist, Mathieu Mercier. “What we feel when we open this box and touch and enjoy its contents is surely close to what Duchamp felt when he created this work originally. It prompts us to contemplate what an author is, and what reproduction means.”

What is modern art? In chronological terms, the term mainly refers to artworks created in the 20th century, but another key element is that such art has characteristics of modernity. It’s impossible to consider what those characteristics may be without referring to Marcel Duchamp. Picasso altered the concept of genres such as painting and sculpture, but Duchamp transformed the concept of art itself, by questioning taken-for-granted ideologies and the underlying systems of everyday life. It’s safe to say that art that originates from such questions is one of the major streams of modern art.

One of Duchamp’s works, titled Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath, Veil Water), comprises a commercial perfume bottle with a photograph of a face on it. The face is Duchamp’s own, dressed up as a woman. The name of the artist is given as Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego, and the photo was taken by the photographer Man Ray. This work upended the understanding of originality, by calling into question both the difference between a product and a work of art, and the identity of the actual creator. In 2009, Belle Haleine was sold at auction for more than ten million dollars. A work initially designed to question the nature of originality ended up being highly valued for its own originality, thus acquiring a new meaning.

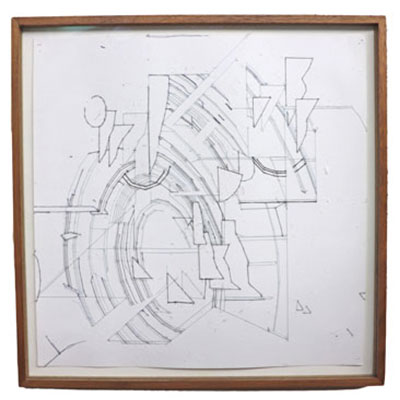

UTokyo’s Komaba Museum has a 1980 replica of Duchamp’s The Large Glass. The people involved in creating this replica, who worked from explanatory materials left behind by Duchamp himself, would surely have formed questions different from those occurring to people who simply view the finished work, questions related to the meaning of the process they were involved in, and why the artist expressed himself in this way. Producing a replica might actually be the type of engagement with art that Duchamp originally hoped for: something different from the usual approach that requires quiet contemplation of the work from an appropriate distance in an art museum.

Questioning something from a standpoint separate from everyday life

The original work is held in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and there are four copies. One of them is part of the permanent collection of the Komaba Museum. To read more about the reproduction project of this giant work, which is over two meters tall, scan this code (Japanese) →

Why is modern art so difficult? I believe it’s because modern art poses questions. Some works do offer answers or a sense of comfort, but beyond these, the distinctive feature of modern art is the way it prompts us to consider things such as what the work actually means, and what it calls into question. It seems difficult because rather than furnishing answers, it poses questions and forces us to think. Modern art allows us to question something from a standpoint separate from everyday life. Many fans of modern art enjoy the way works provide inspiration, make them feel uncomfortable, and evade simple solutions. Even for those who aren’t fans, surely it’s a common human trait to seek things that appeal to our intellect, not just to our emotions.

People who find difficulty in appreciating modern art may well be angry when confronted by something that’s made out to be a valuable artwork but doesn’t make them feel good at all. To tell the truth, I used to be one of those people. I used to prefer art that was emotionally enjoyable, and I couldn’t make any sense of works like Picasso’s cubist paintings. But as I looked at these works more and started to think about why they were constructed in such a way, my intellectual interest was kindled. My struggle to engage with cubist paintings was paralleled in the struggle I experienced in using foreign languages when I was studying abroad. When I became aware of this parallel in my own experience, the difficulty of the paintings began to have a special meaning for me. As I looked at them, questions drifted into my mind and superimposed themselves on my own problems, and I felt that the paintings were offering me some kind of silent support.

Art becomes familiar when it intersects with your own problems

At what stage did art become so difficult, and when did the modern art era begin? These are not the essential questions. The most valuable kind of experience is when, either within an art museum or outside it, you find something that makes you curious, something that speaks to you, and you cherish it. Moreover, it’s not important that you understand every single work on display in a museum. I think it’s more important for you to find something — even one thing — that you feel relates to a problem in your own life.

I’ve been doing research on cubism. Most recently, I’ve been focusing on the way cubist works make use of anatomical knowledge incorporated by artists since olden times, and exploring how anatomical images were used in surrealism. I’ve also been inspired by the conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s, and have developed an interest especially in how the women artists of that period viewed themselves. Art also used to be a masculine domain, but some women artists, feeling uncomfortable with this, sought to destroy the established value codes and call into question the male-centered art scene and society. I’m especially interested in a work by Mary Kelly titled Post-Partum Document. This is an installation on the theme of childbirth, which includes objects such as used diapers and a child’s scribbles, with the addition of comments by Kelly herself. It provides a tense depiction of Kelly’s struggles as a mother and as an artist. Because it contains ideas such as psychoanalysis and Foucault’s discourse, the work has been criticized for being unapproachable by people unfamiliar with such ideas, but it appeals to me because it intersects with problems I face in my own life.

A. Because they enjoy gaps and dialogues (maybe).

Drawing a picture is an act of externalizing something inside yourself, but it usually ends up a little different from your internal image. One of my answers to this question is that it’s enjoyable to see the gap between your image and the picture you produce. This is why children seem to enjoy drawing pictures. When you render the image you had in your mind as a picture it comes out slightly distorted, and that distortion makes it fun. You enter into a dialogue with yourself, and the picture can also become a medium for dialogue with others. Maybe this is why people draw. I believe that even perplexing works of modern art generate all kinds of dialogue.

Kyubisumu Geijutsushi (“History of Cubist Art”) (The University of Nagoya Press, 2019)

Recipient of the 32nd Watsuji Tetsuro Culture Prize, this book sheds light on the development of cubism, a movement that expanded in many directions even beyond the art world.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 45 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of September 2022.

Answered by Hiromi Matsui

Answered by Hiromi Matsui