UTokyo researchers answer questions on 21 GX (Green Transformation) topics from their specialist viewpoints. Through questions that cannot simply be brushed off as someone else’s concerns, take a peek into GX and our world of research.

Q9. Should we use only animal- and plant-based resources as people did in the Edo period?

Some are saying we should learn from Japan’s Edo period (1603—1868) when society flourished without depending on fossil fuels or mineral resources. If we do the same, could we overcome global warming?Answered by Masayuki Tanimoto

Professor, Graduate School of Economics

Japanese Economic History

Economic history as seen through fertilizer

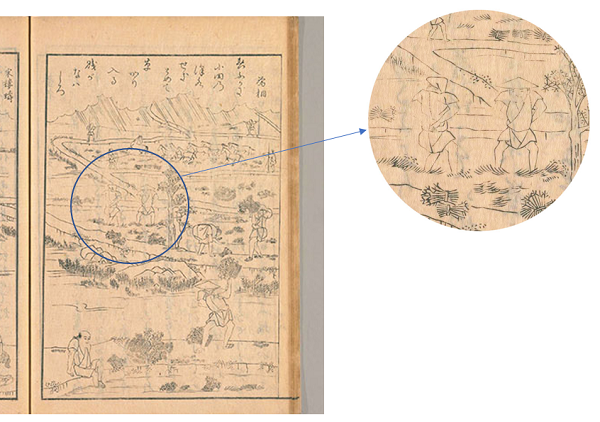

(from the National Diet Library digital archives)

The fertilizer used in 17th-century Japan was a plant-based compost called karishiki which was spread over fields. This compost consisted of cut grass and brushwood such as twigs collected from common land in mountainous areas that was difficult to cultivate. From the latter stages of the Warring States period (1467—1568) to the first half of the Edo period (1603—1868), the population grew as the feudal lords expanded the amount of arable land to increase their income from land taxes. As over-cutting loosened the soil and caused flooding, the shogunate prohibited the excessive collection of the compost materials, and the villages restricted the use of the land from where it was gathered. There was plenty to deter any villager thinking of disregarding these rules. You could not survive if you became an outcast in your own village, and it was also difficult to move to another village. Such deterrents worked as an effective means of protecting resources. However, both resources and land were limited. By the start of the 18th century, the expansion of arable land and the increase in population had both come to a halt.

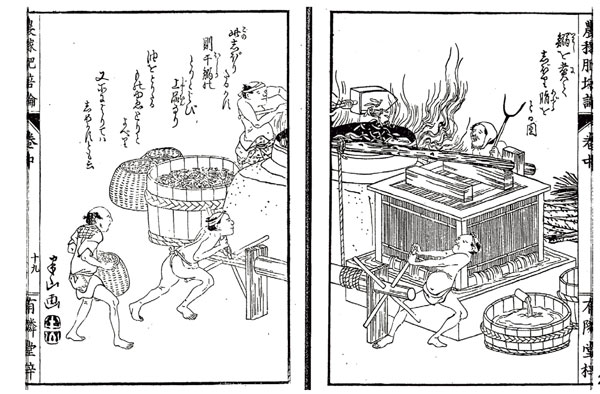

That is when fish-based fertilizers came onto the scene. The by-products left over from the extraction of oils from fish such as sardines and herring made excellent fertilizers. Unlike compost, fish-based fertilizers were commercial fertilizers for which people paid money, and there is a widely held view that these fertilizers helped boost the market economy. Commercial fertilizers were most commonly used by farmers producing cash crops like cotton and rapeseed, but were also utilized for rice production if compost was in short supply. As commercial fertilizers were highly effective, farming remained profitable even when their prices went up. The population started to grow again, and human waste, gathered where people had congregated, was also sold as fertilizer.

As the Meiji period dawned, increases in yields led to a further increase in demand for fertilizers, which was met by importing soybean meal from overseas. Manchuria (Northeast China) was a world-renowned grower of soybeans at that time and had become a supplier of soybean oil to the European chemical industry. When oil was extracted from the soybeans, a huge amount of meal was left behind. Soybean meal therefore became one of the first resources to be transferred in large amounts across the world.

The key to growth was looking outside for resources

(from the National Diet Library digital archives)

Compost and fish fertilizers could be obtained from outside the arable areas, and soybean meal was imported from overseas. This means societies can only grow if they look for and obtain external resources. Although there are differences between renewable animal- and plant-based materials and unrenewable minerals, the key point regarding resources is whether or not they can be traded. In the Edo period, production and consumption was balanced just by using animal- and plant-based resources, and within that scope the population and economy could expand. That growth eventually reached its limit, and further expansion in the Meiji period and thereafter came through international trade. Now we are once again approaching a limit. History shows there is a repeating cycle of expansion -> limit -> innovation -> expansion -> limit, which goes on and on.

While labor-intensive Japanese agriculture becomes more difficult as the population drops, it is predicted that the spread of AI will lead to fewer office jobs. I believe it is worth considering the idea of having a labor force which has moved into tertiary industries move back towards agriculture. One of the good points of the Edo period was that labor was employed according to the availability of renewable animal- and plant-based resources. If we learn from that period and utilize modern technology to make the tough parts easier, we might be able to put people to work on parts where they want take a more hands-on approach.

Based on my interest in indigenous economic development and where small- to mid-sized businesses fit in Japan’s early modern period, I am currently investigating the history of the toy production industry until around 1970. Small backstreet workshops in places like Sumida and Katsushika wards used to function as large workplaces, and they enjoyed a significant presence until the post-war economic boom. Half the working population in those days was employed in small- to mid-sized businesses, driving Japan’s economy forward. The subsequent contraction of this type of business from the 1990s onwards has played a big role in modern Japan’s economic woes. I will continue to look at this in more detail.

Professor Tanimoto’s 2018 video lecture on “The history of animal- and plant-based resources and economic activity” can be viewed in full at

https://ocw.u-tokyo.ac.jp/lecture_1706/. (Japanese language only)

Nihon Keizai-shi: Kinsei kara Gendai made (The Economic History of Japan: From the Early Modern Era to the Present)

(Yuhikaku Publishing, 2016)

A step-by-step explanation of the past 400 years of the Japanese economy, from peasant society to the present day, highlighting the “continuations and interruptions.”

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 46 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2023.