Canine research at UTokyo

Veterinary surgery, ethology, robotics, archaeology, chronological dating, law and animal assisted intervention, veterinary epidemiology, classic literature, and contemporary literature – specialists in these nine fields introduce their canine-related research activities.

Dogs and veterinary surgery

Treating canine cancers through a new type of immunotherapy

Takayuki Nakagawa

Associate Professor, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences

With advancements in veterinary medicine in recent years, the average canine lifespan has been getting longer. As a result, just as in the case of humans, the major cause of canine death is now malignant tumors (cancers). Associate Professor Nakagawa is researching canine cancers at the Veterinary Medical Center and the Laboratory of Veterinary Surgery.

In the following, the associate professor shares details about the present state of development of immunotherapy, his primary area of focus.

Dogs are living longer, and they suffer from the same diseases as humans

The average dog’s lifespan is getting longer. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Pet Food Association, the average lifespan has risen from about seven years in the 1980s to around 13 years in the 2000s, and has reached 14.76 years as of 2022. This is due to factors such as the progress made in the prevention of infectious diseases, a rising tendency to keep dogs indoors and an increase in veterinary checkups. However, the extended lifespan has caused dogs to suffer diseases similar to the lifestyle-related diseases experienced by humans. In fact, the biggest cause of death among dogs is now cancer, which is the uncontrolled proliferation of malignant tumors. These tumors are different from warts or calluses caused by external friction. A tumor that metastasizes is called a cancer.

At the Laboratory of Veterinary Surgery, I mainly conduct research into solid cancers. For a solid cancer, the most effective treatment method is to remove it. If it spreads to another part of the body, however, we cannot treat it clinically with surgery and must find another way of dealing with it through research. This is how our laboratory approaches cancer treatment.

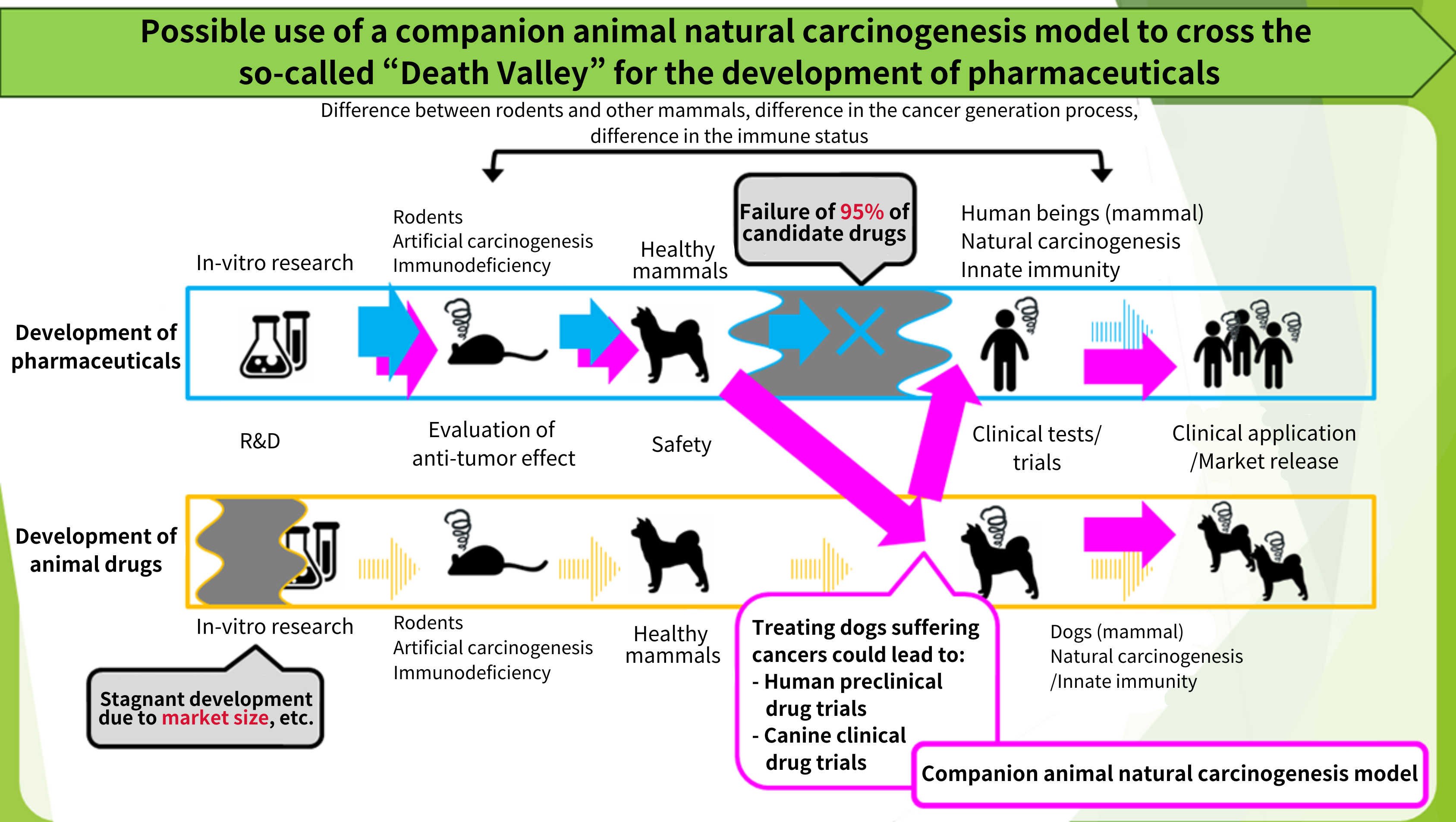

For cancers, there are three typical treatment methods: surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy (using anti-cancer drugs and other such agents). A fourth option is immunotherapy. The idea of making immune cells attack cancer cells, which the body recognizes as foreign, has been around for a long time, but until recently was not considered very effective. The development of an immune checkpoint inhibitor called Opdivo by Dr. Tasuku Honjo and others became a game changer, however, after it was revealed that immune checkpoint molecules on cell membranes, such as PD-1 and PD-L1, prevent immune cells from attacking cancer cells. By using a drug (checkpoint inhibitor) to remove this “brake,” immune cells become able to attack cancer cells more proactively. But the effectiveness of the drug differs substantially by patient, and as Opdivo is very expensive, it is better to limit its use to those for whom it is truly effective, for which an indicator (biomarker) is needed.

Protein that contributes to growth of breast cancer cells also expressed in dogs

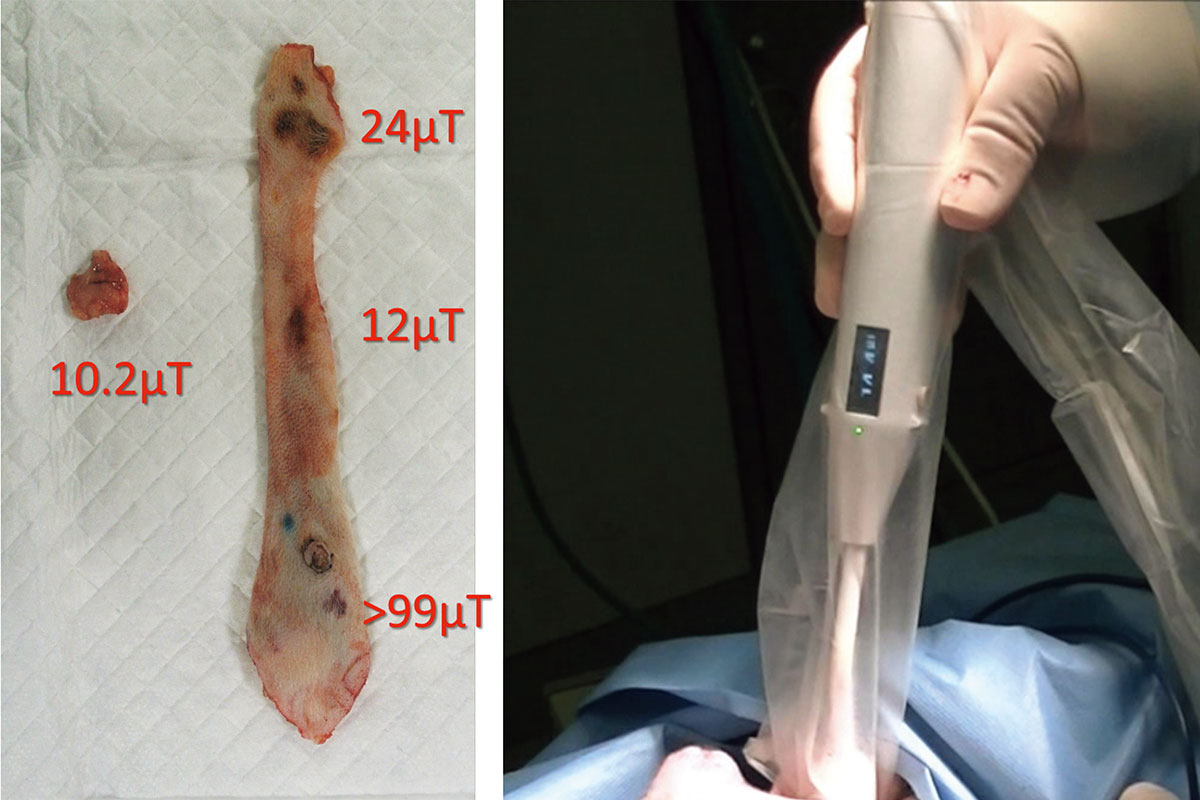

The epidermal protein HER2 contributes to the growth of cancer cells. The expression of this protein is particularly evident in human breast cancer cells, and dealing with it is considered an effective cancer treatment. Because no clear data were available for dogs regarding the expression of this protein, we conducted research and have confirmed the clear expression of HER2 in canine anal sac adenocarcinoma and lung cancer cells. We therefore think that these canine cancers might be curable by using the existing HER2 inhibitor developed for the treatment of human breast cancer.

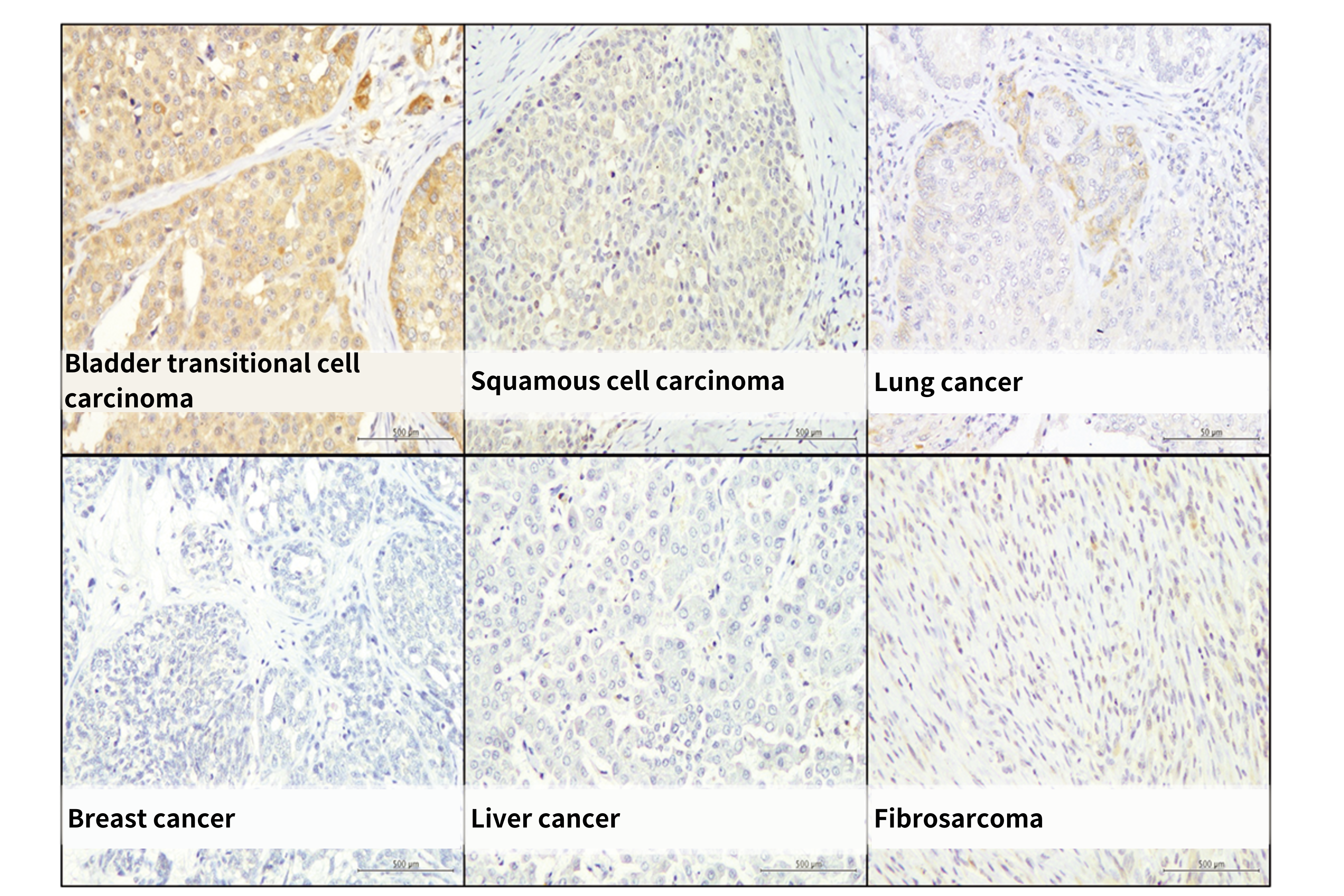

For various types of cancers, changes that cause cancer cells to grow are not limited to those involving HER2 genes. Based on this recognition, we conducted research to identify other changes that might have a significant impact. As a result, we have found that an enzyme called IDO1 also contributes to the growth of cancer cells. Specifically, this enzyme, which synthesizes protein, restricts the function of immune cells, thereby allowing cancer cells to proliferate. The expression of IDO1 is also abundant in canine bladder cancer cells. As a result of conducting this research, we know that by using medicine to restrict the function of IDO1, we can suppress the proliferation of cancer cells. In other words, instead of killing cancer cells directly, we restrict the function of the enzyme that is suppressing the immune cells.

If we use a drug to kill cancer cells directly, it will also attack other cells, imposing a tremendous burden on the body. That’s why we see hair loss and other such side effects when anti-cancer agents are used. Restricting the function of the IDO1 enzyme does not harm the body in this way, so this therapy also can be used for old dogs. Unfortunately, we cannot at this time fully eliminate cancer using this method; we can only reduce the size of the tumors by 20 to 30%. It is therefore important to use it in combination with other promising treatments. For example, we may additionally need to adopt another type of immunotherapy such as using an immune checkpoint inhibitor, or use a gene modification therapy called CAR-T. We will continue to carry out clinical tests for these therapies at the Veterinary Medical Center.