Coming together to tackle the SDGs

Coming together to tackle the SDGs

Teruo Fujii, president of the University of Tokyo, and Ed Gerstner, the chair of Springer Nature’s SDG programme, discuss the rallying call that the SDGs represent and how they can be realized through embracing collaboration between diverse parties.

Adopted by all 193 United Nations Member States in 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations outline the key challenges facing humanity and the planet and offer a bold vision for realizing a better world. Achieving these goals will require drawing on the ingenuity and expertise of a diverse array of people and institutions.

The University of Tokyo and the scientific publisher Springer Nature play very different roles in the research process — one hosts and supports scientists conducting frontline research, while the other helps them disseminate their latest findings to a global audience. But the two organizations have a shared vision for tackling the SDGs, a vision that will be explored in a joint event, “Energy systems at the interface of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): technologies and responses for a sustainable future,” to be held online and at the University of Tokyo on 29th March, 2022.

The event, which will be held in English with simultaneous Japanese interpretation, will focus on how energy systems intersect with multiple SDGs, especially those related to Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7); Industry Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9); Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12); and Climate Action (SDG 13). It will include two keynote talks and a panel discussion involving five experts in the area of energy.

In anticipation of this event, Teruo Fujii, president of the University of Tokyo, and Ed Gerstner, director of Journal Policy and Strategy at Springer Nature, talked to each other about the strategies their respective organizations are implementing to help realize the SDGs.

Bringing diverse parties together

The ability of the SDGs to draw diverse parties together as they work towards achieving common goals of global importance was a thread that ran throughout the conversation. “The challenges we face are existential,” Gerstner commented. “But they have the opportunity to bring us together.”

This has played out in Gerstner’s own experience as he has personally witnessed the willingness of people at Springer Nature to give freely of their time and abilities when they are offered the opportunity to contribute to the common good and transform the world. “Prior to working on the SDGs, it was sometimes a challenge to ask people to help with my projects because they were very busy and unable to commit themselves,” Gerstner said. “But when I started working on the SDGs, I found that people were always happy to accede to requests. Everyone wants to play a part in making the world a better place.” One reason for this willingness to contribute is that, “When it comes to the SDGs, we are all stakeholders. We all have an interest in preserving the planet.”

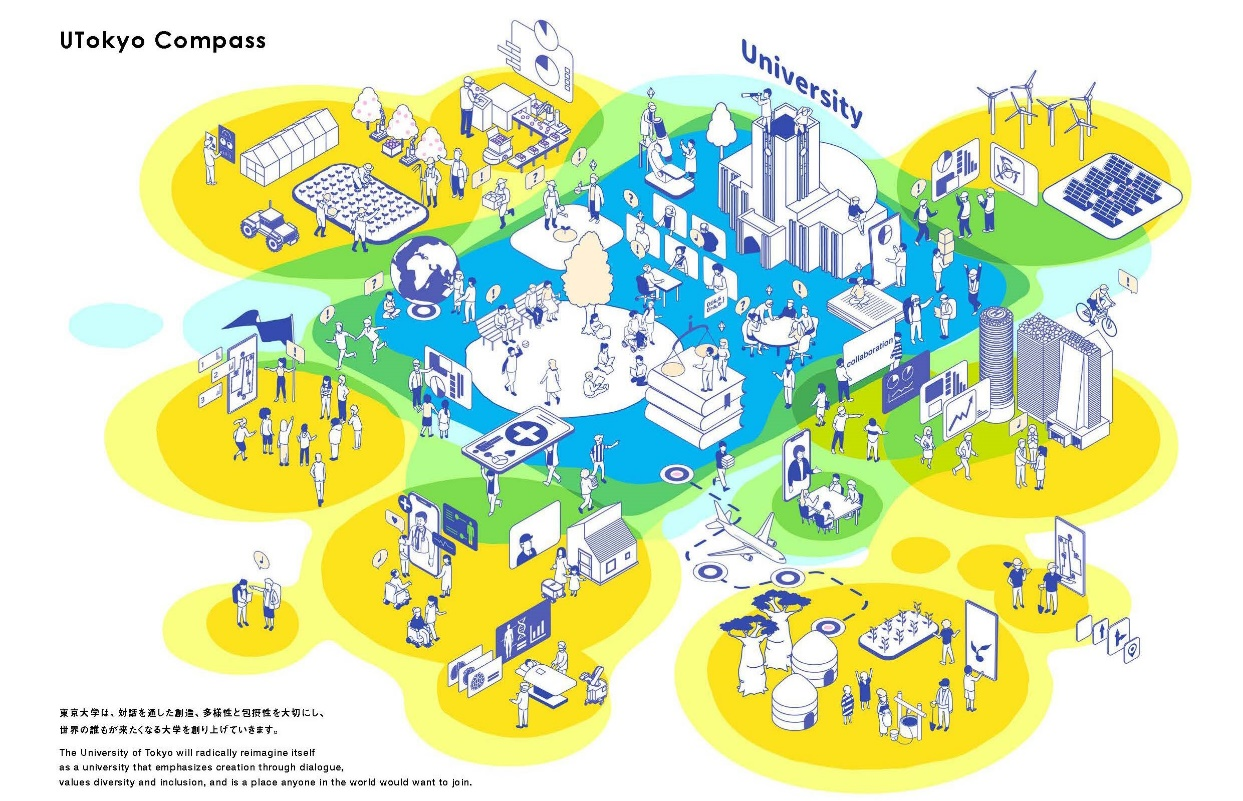

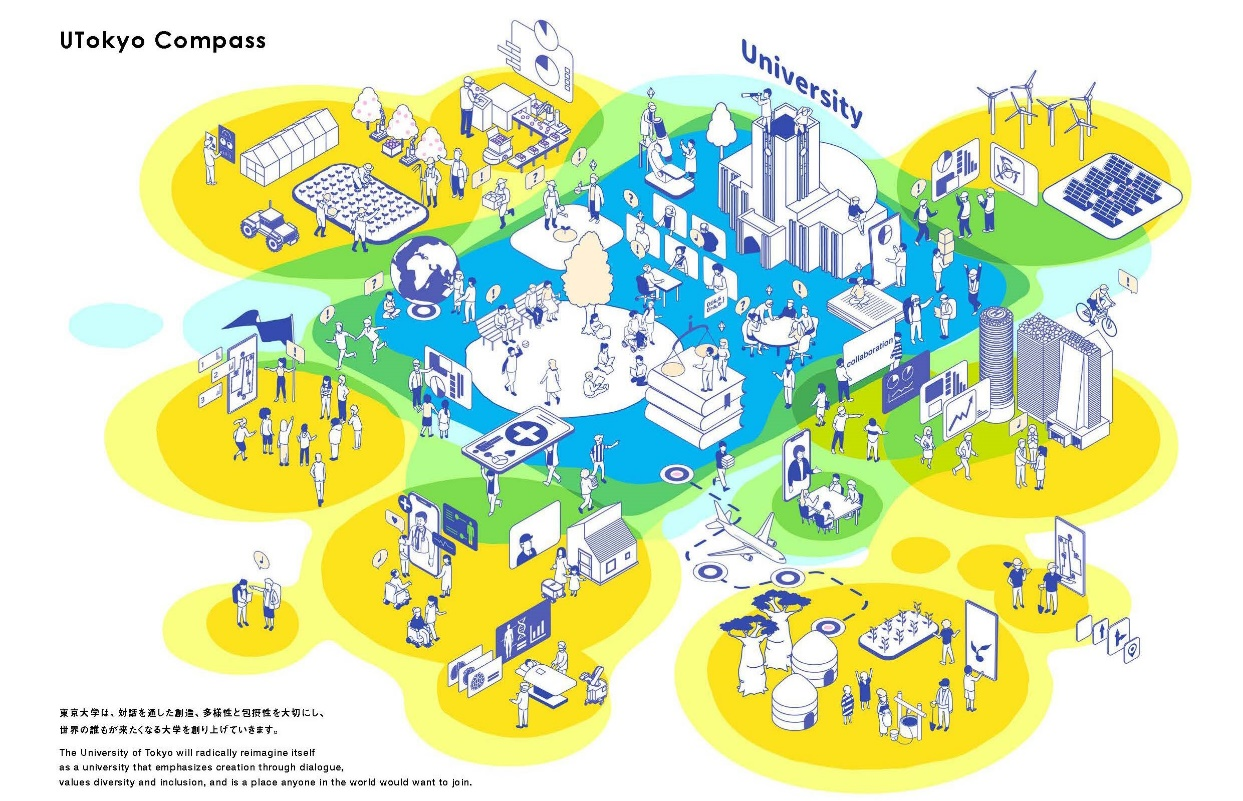

Fujii concurred, likening the various contributions that each person brings to the table as different instruments in an orchestra. “It’s not a single melody; rather you have multiple parts playing in harmony,” Fujii said. “When people with different backgrounds and expertise discuss the same questions, it provides a fertile ground for coming up with new ideas. Every researcher in our university can make an important contribution to this forum.” Recognizing the vital importance of promoting dialogue, diversity, inclusivity and broader societal impact, the University of Tokyo released in September 2021 UTokyo Compass — a comprehensive statement of the guiding principles that lays down the ideals and direction the university should pursue. This has been encapsulated in its motto: “Into a Sea of Diversity: Creating the Future through Dialogue.”

The challenges posed by the SDGs demand a pooling of all available resources. “One of the key challenges for the SDGs is that they are so broad, so interconnected and so complex that we won’t be able to meet the goals using just one discipline,” said Gerstner. “It’s not going to be solved by physicists alone, or chemists alone, or biologists alone, or engineers alone. You need to bring everyone to the table, including researchers in the humanities and social sciences.”

The interdisciplinary nature of the challenges posed by SDGs is reflected in a change in mindset among students these days, Gerstner noted. “Back in the 1990s, we would go to university in order to become physicists or chemists or biologists,” he said. “But increasingly these days, students are going to university to learn to become problem solvers. And so they want to learn the physics, the chemistry, the engineering, the computer science, the mathematics, and the biology they need to solve the problems that face us.”

Getting down to specifics

Given their leadership roles in their respective institutions, both Fujii and Gerstner view the SDGs from a big-picture perspective. But it’s also helpful to consider specific examples of the kind of transdisciplinary research that will realize the SDGs. Fujii is well placed to do this. An engineer by background, his research focuses on microfluidic systems and their application to deep-sea research. One interdisciplinary project he has launched based on his work on underwater technology is the Ocean Monitoring Network Initiative (OMNI) project, which is developing flexible, low-cost ocean monitoring sensors that anyone can deploy in the sea. This project aims to create a platform that allows anyone to participate in oceanographic research.

Fujii pointed out that there is still so much we don’t know about the oceans. For example, only about 20% of the ocean bed topography has been measured, whereas we have mapped the entire lunar surface. Measurements are vital for optimizing ocean management. In addition, parameters feed into models of climate change and other phenomena. As Gerstner put it, “If you can’t measure something, you can’t fix it.”

The problem with performing measurements on the oceans is their sheer size. For example, the Argo programme, an international project that measures water properties in the oceans on a global scale, has about 4,000 monitoring buoys floating in the world’s oceans — roughly one buoy for an area of 300 kilometres x 300 kilometres on average. Since high-performance sensors are expensive to fabricate, the OMNI project is seeking to develop small, low-cost sensing platforms that are simple enough that high-school students could be taught how to construct them. “We believe this will lead to many more data points, which will provide a much more detailed picture of the current state of the world’s oceans,” said Fujii. “Importantly, at the same time, the project can cause more people to think of the health of the oceans as a personal matter.” As Gerstner pointed out, this project ticks all the boxes — it uses cutting-edge science to tackle a critical question, involves the community, and is affordable. This platform will play a critical role in monitoring the planet’s health and contributing to the realization of multiple SDGs; the oceans are clearly crucial for SDG 14 (Life Below Water), as well as SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), among others.

Lowering barriers and reversing the trend

The growing importance of the SDGs for guiding policy and practice has created a real need for universities to rethink how to conduct research in order to support the implementation of the SDGs, as well as more broadly how they operate and engage with the wider society. This is reflected in one of the core values of UTokyo Compass, namely making the university a better place that anyone in the world would like to join. That means making it more open to society. “The university itself is surrounded by high physical and mental walls,” said Fujii. “But now the idea is to lower the barriers and expand into society so that people of all kinds can gather, engage in dialogue, and create new knowledge. Together with diverse people from all walks of life, we will devise ways to make full use of the place provided by the university. I believe that the cycle of dialogue and mutual confidence will open up a bright new future.”

The University of Tokyo’s philosophy on SDG research is expressed in the UTokyo Future Society Initiative (UTokyo FSI), which was framed in 2017 and states that the university, “shall utilize to the maximum extent possible the SDGs, which are congruent with the University’s mission, to set into motion collaborative projects which will contribute to the future of humanity and the planet.” There are currently more than 200 projects under the FSI that are addressing the SDGs. This emphasis on the SDGs is a deliberate effort to buck the trend, which has seen Japan’s global ranking for the share and quality of SDG research output decline steadily over the past ten years1. And it is bearing fruit, as the University of Tokyo published more studies in 2021 related to the SDGs than any other institution in Japan2.

Reasons to be optimistic

Despite the immense challenges posed by the SDGs, both Gerstner and Fujii share a common optimism as they look to the future.

Explaining the motivation behind the establishment of Springer Nature’s SDG programme, Gerstner said: “We created the programme because, as people who believe in the transformative power of scholarship and research, we felt it was our duty to make the world a better place. It’s our duty to do all we can to protect the planet.” And the response has been gratifying: “It has been really powerful and motivating to see everyone in the company getting behind the SDGs.”

This article is also published on The Source, Springer Nature’s blog site.

Teruo Fujii, president of the University of Tokyo, and Ed Gerstner, the chair of Springer Nature’s SDG programme, discuss the rallying call that the SDGs represent and how they can be realized through embracing collaboration between diverse parties.

Adopted by all 193 United Nations Member States in 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations outline the key challenges facing humanity and the planet and offer a bold vision for realizing a better world. Achieving these goals will require drawing on the ingenuity and expertise of a diverse array of people and institutions.

The University of Tokyo and the scientific publisher Springer Nature play very different roles in the research process — one hosts and supports scientists conducting frontline research, while the other helps them disseminate their latest findings to a global audience. But the two organizations have a shared vision for tackling the SDGs, a vision that will be explored in a joint event, “Energy systems at the interface of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): technologies and responses for a sustainable future,” to be held online and at the University of Tokyo on 29th March, 2022.

The event, which will be held in English with simultaneous Japanese interpretation, will focus on how energy systems intersect with multiple SDGs, especially those related to Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7); Industry Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9); Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12); and Climate Action (SDG 13). It will include two keynote talks and a panel discussion involving five experts in the area of energy.

In anticipation of this event, Teruo Fujii, president of the University of Tokyo, and Ed Gerstner, director of Journal Policy and Strategy at Springer Nature, talked to each other about the strategies their respective organizations are implementing to help realize the SDGs.

Bringing diverse parties together

The ability of the SDGs to draw diverse parties together as they work towards achieving common goals of global importance was a thread that ran throughout the conversation. “The challenges we face are existential,” Gerstner commented. “But they have the opportunity to bring us together.”

This has played out in Gerstner’s own experience as he has personally witnessed the willingness of people at Springer Nature to give freely of their time and abilities when they are offered the opportunity to contribute to the common good and transform the world. “Prior to working on the SDGs, it was sometimes a challenge to ask people to help with my projects because they were very busy and unable to commit themselves,” Gerstner said. “But when I started working on the SDGs, I found that people were always happy to accede to requests. Everyone wants to play a part in making the world a better place.” One reason for this willingness to contribute is that, “When it comes to the SDGs, we are all stakeholders. We all have an interest in preserving the planet.”

Fujii concurred, likening the various contributions that each person brings to the table as different instruments in an orchestra. “It’s not a single melody; rather you have multiple parts playing in harmony,” Fujii said. “When people with different backgrounds and expertise discuss the same questions, it provides a fertile ground for coming up with new ideas. Every researcher in our university can make an important contribution to this forum.” Recognizing the vital importance of promoting dialogue, diversity, inclusivity and broader societal impact, the University of Tokyo released in September 2021 UTokyo Compass — a comprehensive statement of the guiding principles that lays down the ideals and direction the university should pursue. This has been encapsulated in its motto: “Into a Sea of Diversity: Creating the Future through Dialogue.”

The challenges posed by the SDGs demand a pooling of all available resources. “One of the key challenges for the SDGs is that they are so broad, so interconnected and so complex that we won’t be able to meet the goals using just one discipline,” said Gerstner. “It’s not going to be solved by physicists alone, or chemists alone, or biologists alone, or engineers alone. You need to bring everyone to the table, including researchers in the humanities and social sciences.”

The interdisciplinary nature of the challenges posed by SDGs is reflected in a change in mindset among students these days, Gerstner noted. “Back in the 1990s, we would go to university in order to become physicists or chemists or biologists,” he said. “But increasingly these days, students are going to university to learn to become problem solvers. And so they want to learn the physics, the chemistry, the engineering, the computer science, the mathematics, and the biology they need to solve the problems that face us.”

Getting down to specifics

Given their leadership roles in their respective institutions, both Fujii and Gerstner view the SDGs from a big-picture perspective. But it’s also helpful to consider specific examples of the kind of transdisciplinary research that will realize the SDGs. Fujii is well placed to do this. An engineer by background, his research focuses on microfluidic systems and their application to deep-sea research. One interdisciplinary project he has launched based on his work on underwater technology is the Ocean Monitoring Network Initiative (OMNI) project, which is developing flexible, low-cost ocean monitoring sensors that anyone can deploy in the sea. This project aims to create a platform that allows anyone to participate in oceanographic research.

Fujii pointed out that there is still so much we don’t know about the oceans. For example, only about 20% of the ocean bed topography has been measured, whereas we have mapped the entire lunar surface. Measurements are vital for optimizing ocean management. In addition, parameters feed into models of climate change and other phenomena. As Gerstner put it, “If you can’t measure something, you can’t fix it.”

The problem with performing measurements on the oceans is their sheer size. For example, the Argo programme, an international project that measures water properties in the oceans on a global scale, has about 4,000 monitoring buoys floating in the world’s oceans — roughly one buoy for an area of 300 kilometres x 300 kilometres on average. Since high-performance sensors are expensive to fabricate, the OMNI project is seeking to develop small, low-cost sensing platforms that are simple enough that high-school students could be taught how to construct them. “We believe this will lead to many more data points, which will provide a much more detailed picture of the current state of the world’s oceans,” said Fujii. “Importantly, at the same time, the project can cause more people to think of the health of the oceans as a personal matter.” As Gerstner pointed out, this project ticks all the boxes — it uses cutting-edge science to tackle a critical question, involves the community, and is affordable. This platform will play a critical role in monitoring the planet’s health and contributing to the realization of multiple SDGs; the oceans are clearly crucial for SDG 14 (Life Below Water), as well as SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), among others.

Lowering barriers and reversing the trend

The growing importance of the SDGs for guiding policy and practice has created a real need for universities to rethink how to conduct research in order to support the implementation of the SDGs, as well as more broadly how they operate and engage with the wider society. This is reflected in one of the core values of UTokyo Compass, namely making the university a better place that anyone in the world would like to join. That means making it more open to society. “The university itself is surrounded by high physical and mental walls,” said Fujii. “But now the idea is to lower the barriers and expand into society so that people of all kinds can gather, engage in dialogue, and create new knowledge. Together with diverse people from all walks of life, we will devise ways to make full use of the place provided by the university. I believe that the cycle of dialogue and mutual confidence will open up a bright new future.”

The University of Tokyo’s philosophy on SDG research is expressed in the UTokyo Future Society Initiative (UTokyo FSI), which was framed in 2017 and states that the university, “shall utilize to the maximum extent possible the SDGs, which are congruent with the University’s mission, to set into motion collaborative projects which will contribute to the future of humanity and the planet.” There are currently more than 200 projects under the FSI that are addressing the SDGs. This emphasis on the SDGs is a deliberate effort to buck the trend, which has seen Japan’s global ranking for the share and quality of SDG research output decline steadily over the past ten years1. And it is bearing fruit, as the University of Tokyo published more studies in 2021 related to the SDGs than any other institution in Japan2.

Reasons to be optimistic

Despite the immense challenges posed by the SDGs, both Gerstner and Fujii share a common optimism as they look to the future.

Explaining the motivation behind the establishment of Springer Nature’s SDG programme, Gerstner said: “We created the programme because, as people who believe in the transformative power of scholarship and research, we felt it was our duty to make the world a better place. It’s our duty to do all we can to protect the planet.” And the response has been gratifying: “It has been really powerful and motivating to see everyone in the company getting behind the SDGs.”

Fujii finds encouragement in the rapid rate of scientific and technological progress. Citing the example of the invention of the printing press in the 15th century and how it revolutionized the propagation of knowledge, Fujii said: “The speed of technological change is incredibly fast now, in even in a short period of time, we can make a huge difference in terms of disseminating scientific knowledge. So I am very optimistic.”

Partnering for impact

Throughout their discussion, both Fujii and Gerstner evoked the necessity of partnerships, transdisciplinary cooperation, and inclusivity for catalysing broader societal impact and progress towards meeting the SDGs. These notions have been central in the longstanding collaboration between the University of Tokyo and Springer Nature, which includes the forthcoming joint symposium on the intersection between energy systems and the SDGs.

To find out more about the joint event and to register for it, visit this site: https://www.springernature.com/jp/campaign/202203-EN

1. Science, Digital; Wastl, Juergen; Porter, Simon; Draux, Hélène; Fane, Briony; Hook, Daniel (2020): Contextualizing Sustainable Development Research. Digital Science. Report. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12200081.v2

2. Based on papers listed in Dimensions (https://app.dimensions.ai).

This article is also published on The Source, Springer Nature’s blog site.