Little-known realities of the ancient Olympic Games

Research, education and legacies related to the sporting event

The Olympic and Paralympic Games will be held in Tokyo for the first time in more than half a century. The University of Tokyo, which is also located in the metropolis, has a long history of involvement with the Games. As you learn about UTokyo’s contributions to this global sporting event, the blue used in the Olympic and Paralympic emblem may very well start to take on the light blue hue of the University’s school color.

| Western History |

Little-known realities of the ancient Olympic Games

Held over a period ten times longer than the modern Olympic Games

Mention the Olympics and imagery from the modern Olympics usually comes to mind, but the ancient Olympic Games were somewhat different. In fact, they differed in many ways including their objectives, the competitive events that were held, their host countries, and the rewards they afforded their winning athletes. However, the historical record on ancient Olympic festivals still provides numerous insights. In preparation for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, let’s read the following commentary from a scholar on the history of ancient Greece.

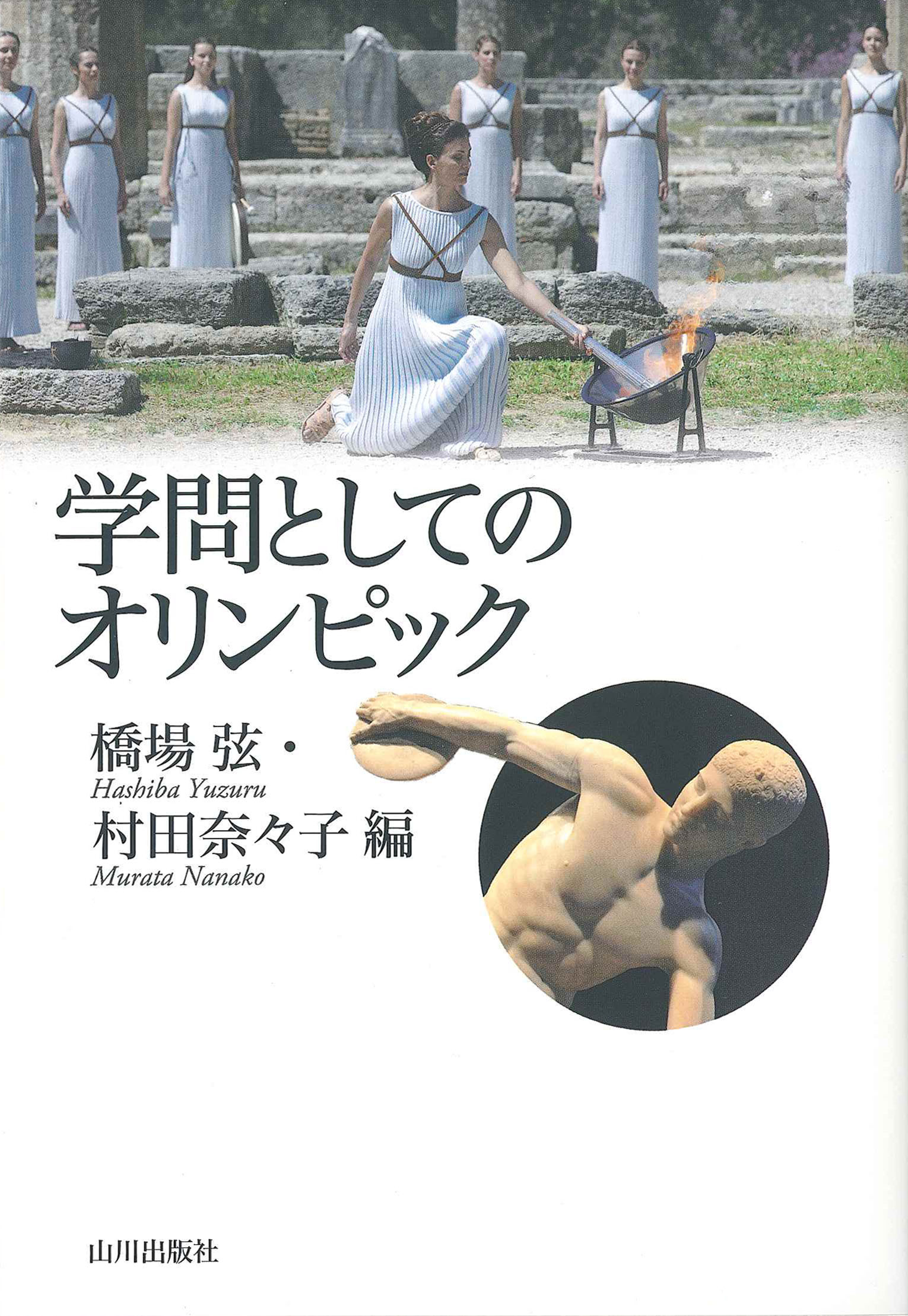

Gakumon to shite no Olympic [The Olympics as an academic discipline] is a work based on lectures in the Junior Division of College of Arts and Sciences (Edited by Yuzuru Hashiba and Nanako Murata; Yamakawa Shuppansha). It contains articles written by not only Hashiba but also Professor Noburu Notomi (Greek philosophy) and Professor Senshi Fukushiro (Biomechanics).

Gakumon to shite no Olympic [The Olympics as an academic discipline] is a work based on lectures in the Junior Division of College of Arts and Sciences (Edited by Yuzuru Hashiba and Nanako Murata; Yamakawa Shuppansha). It contains articles written by not only Hashiba but also Professor Noburu Notomi (Greek philosophy) and Professor Senshi Fukushiro (Biomechanics).

For almost 1,200 years, the festivals of the ancient Olympic Games were held every four years in Olympia, Greece, starting with the first Olympic Games in 776 B.C. to the 293rd Olympic Games in 393 A.D. Had the ancient Greeks not thought of holding an international sporting event once every four years, the Olympic Games would not be one of the pleasures of our modern age.

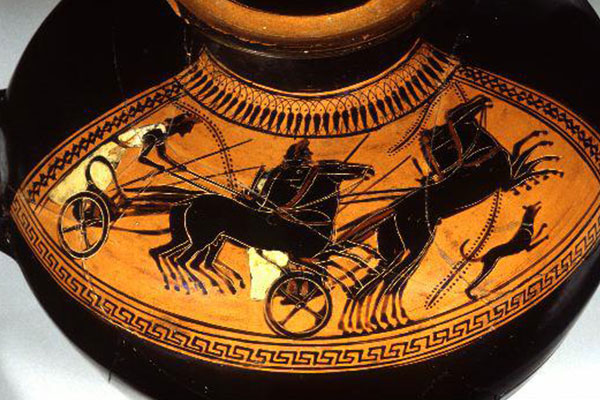

The ancient Olympics were held once every four years around the second or third full moon following the summer solstice, a period that coincides with early August on our modern calendar. Initially, a one-stadion (approx. 190 meters) sprint was the only competitive event, but other events were added over time, and most had become an established part of the Games by the 5th Century B.C. These ranged from sprints, middle-distance runs, the hoplitodromos foot race, and other track events to the highly popular four-horse chariot race, wrestling, boxing, and other sparring events, and the ancient pentathlon comprising a series of field events (the javelin throw, discus throw, broad jump, sprints, and wrestling matches).

The most significant difference compared to the modern Games was that the ancient Olympics was a religious festival held to honor Zeus, the king of the Greek gods. The ancient Greeks viewed the essence of religion as a reciprocal relationship between humanity and the gods. As gratitude for the prosperity and happiness provided, humans offered the gods a variety of gifts in return. The ancient Olympics represented the highest honor dedicated to Zeus.

The small state of Elis, located somewhat to the northwest of Olympia, was the host for the ancient Games. Elis was much smaller and weaker than Athens or Sparta and also less developed. On the other hand, its resistance to influence from its larger neighbors along with its stance of political neutrality was the factor that conversely added to the prestige of the festivals of Olympia.

The notion of banning participation by professional athletes was never a part of the ancient Olympics. The English “athlete” derives from the Greek athlētēs, a term that referred to the “competitors for the athlon (award).” In other words, if we follow Greek conventional wisdom, true athletes were those who competed to win awards. Indeed, at the time, Athens had laws that granted Olympic champions 500 drachmas, a huge monetary reward.

That said, the official prize awarded to champions in Olympia was a single wreath of olive shoots taken from trees grown on sacred ground. Olympia’s international prestige was assured precisely because it awarded winning athletes honor, not monetary prizes.

During the Olympic Games, participating nations adhered to the sacred truce (ekecheiria) of the Olympics and were strictly prohibited from using military force on the roads to/from and in the sanctuary of Olympia. This was not a manifestation of the ideal of achieving world peace, but rather a pragmatic arrangement aimed at ensuring the safety and security of the athletes.

It is widely known that over their 120-year history, the modern Olympic Games have been suspended twice by world wars and harmed by a series of incidents including the killing of athletes by terrorists (1972) and retaliatory boycotts led by major powers (1980, 1984). By contrast, the ancient Olympic Games were never interrupted by acts of war even once over their long 1,200-year history, a period tenfold that of the modern Games. Reverence toward the gods simply did not allow that.

Having been tossed about by the forces of commercialism and logic of global capitalism, what course will the modern Olympic Games take in the years ahead? My hope is that the Olympics will not lose its value as something sacred that cannot be measured in monetary terms.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 40 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2020.

By Yuzuru Hashiba

By Yuzuru Hashiba