UTokyo facilities that have supported Japan’s Olympics

Research, education and legacies related to the sporting event

The Olympic and Paralympic Games will be held in Tokyo for the first time in more than half a century. The University of Tokyo, which is also located in the metropolis, has a long history of involvement with the Games. As you learn about UTokyo’s contributions to this global sporting event, the blue used in the Olympic and Paralympic emblem may very well start to take on the light blue hue of the University’s school color.

UTokyo facilities that have supported Japan’s Olympics

People are not the only elements of UTokyo that have supported Japan’s Olympic endeavors. UTokyo facilities for athletic events, the training of national teams and foreign athletes, and experiments aimed at ensuring victory have all had an instrumental role. This article showcases facilities that have contributed to the festivals of sports and peace in their respective locales and periods.

Kemigawa Athletic Grounds

In addition to its five football grounds, the Kemigawa facility also includes fields for rugby, American football, baseball and hockey, as well as eight tennis courts. The football grounds are available for public use in two-hour increments for a fee of 1030 yen.

The project to build the Kemigawa Athletic Grounds was launched under the direction of UTokyo’s 12th President, Mataro Nagayo. “Building our grounds with our own hands” was enlisted as the project’s slogan. A student labor service organization was assembled chiefly from members of the Athletic Foundation, and by the summer of 1938, a cumulative total of 1174 students had completed the task of leveling the fields for this facility. Although the initial stages of work on the Kemigawa grounds were implemented through meaningful volunteer action, wartime regulations made further work difficult, and the vast fields were instead diverted for use as farmland to offset shortages of food. Following the war, demand for such farmland resources declined, allowing the fields to be transformed by UTokyo alumni volunteers into a golf course. The grounds were opened to members of the golfing public, with a section reserved for physical education classes for the students in the College of Arts and Sciences. However, in 1962, following remarks made at the Diet over how the grounds were being used, it was decided to return them to their original purpose.

At the time, the Tokyo Olympics were not far off, and Professor Kitsuo Kato (physical education) was working as a research member on sports science in the athletes’ strengthening committee. Recognizing that Japan lacked adequate turf-covered grounds required for performance training, Kato proposed utilizing the vast grass-covered fields of the Kemigawa area for that purpose. All interested stakeholders accepted this idea and development proceeded with public funding as well as assistance from the Japan Amateur Sports Association, at last transforming the Kemigawa area into a highly functional athletic facility complex.

In 1964, Japan’s national football team began utilizing the Kemigawa grounds for a three-month period of performance training. This gave the team access to turf-covered grounds as smooth as a carpet, a gymnasium with high windows that facilitated practice-kicking of soccer balls even in inclement weather, and a cross-country course equipped with a rich mix of high and low sections that were ideal for power training. On October 14, the team upset powerhouse Argentina 3-2 at the Komazawa Stadium and brilliantly advanced upward through the group league rankings. The course the national team’s players had used to build their strength was also used as a course for a cross-country event, the final leg of the modern pentathlon competition. On October 15, 25 athletes from 15 nations were lined up, after having completed the events in horsemanship, fencing, marksmanship and swimming. Although it had rained two days earlier, on this day they had a clear autumn sky with not a single cloud in sight. With Japan’s Crown Prince (the current Emperor Emeritus) watching, the cross-country race unfolded over a 4000-meter course. The Hungarian runner Ferenc Torok led with his point total and shook off the USSR’s Igor Novikov to win the race. In the team competition, the USSR stretched its lead over the second-place US to win by a wide margin. Although a commemorative plaque is all that remains now, the flame of the sacred torch from Olympia did once shine over Kemigawa.

The plaque is installed in the reception lobby of the Kemigawa Seminar House (lodging capacity for 196 individuals). The USSR runner Igor Novikov, who finished second in the individual competition, is listed as a member of the winning team.

The cross-country course runs over grounds that include the Jomon-era archaeological sites of Genbansho, Nakayatsu, and Tsurumaki as well as the excavation site where the over 2000-year-old seeds of the Oga lotus were discovered. Cross-country runners from the nearby Fujitsu Track & Field team also come here to practice.

A welcome reception was held in the gymnasium following the cross-country events. Although the cross-country race had been scheduled to be held in downtown Tokyo, the venue was changed nine months prior to the race date in response to strong demands from athletic organizations.

Wind tunnel experimental facilities (Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, Building 1)

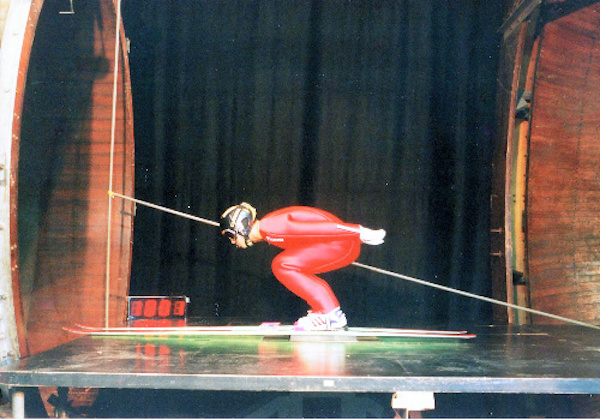

Building 1 of the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology houses a 3-meter wind tunnel constructed of wood that was designed to investigate aerodynamic drag with artificially generated wind forces. This experimental facility played a role in the development of the Kokenki, a long-range research aircraft that holds the world record for long-distance flight, and the YS-11 domestic passenger airplane. The wind tunnel was built under the direction of Professor Theodore von Kármán, known as the father of aeronautical engineering. It has been used to test human posture in ski jumps, thus contributing to the sweep of the winner’s podium at the Sapporo Winter Olympics by the three members of the “Hinomaru Squadron”: Yukio Kasaya, Akitsugu Konno, and Seiji Aochi, and aiding the search for the ideal posture by Masahiko Harada and Kazuyoshi Funaki, two ski jumpers that competed at the Nagano Winter Olympics. UTokyo facilities have made solid contributions to the Winter Olympics.

Komaba athletic fields

The Olympic Village for the 1964 Tokyo Games was built on the former site of the US military’s Washington Heights housing complex (now Yoyogi Park). The nearby Komaba Campus was used by foreign track-and-field athletes as a practice ground. Athletic Field 1 was used by athletes competing in the track, jumps and shot-put events, while the rugby field served for javelin throw practice. The baseball field was used for the discus throw while Athletic Field 2 was put into use for practice in the hammer throw. Additionally, the just-completed training gymnasium was used for athlete muscle training. Although now showing their age, the Komaba facilities were considered innovative in their heyday and essentials for the development of world-leading athletes. They were developed with public funding. The drive to expand Komaba’s sports environment was one of the benefits that derived from the Olympic Games.

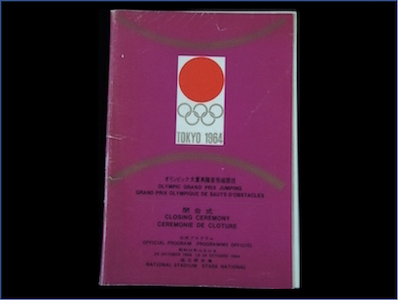

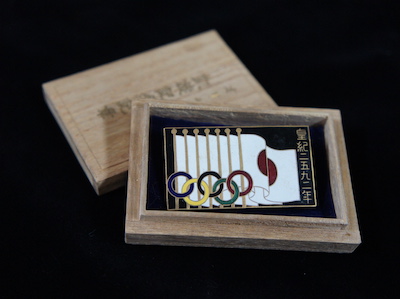

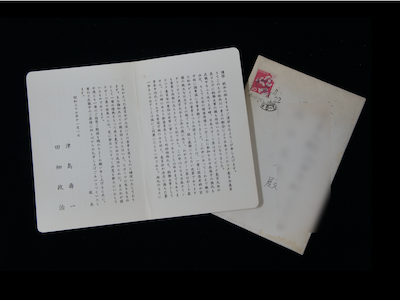

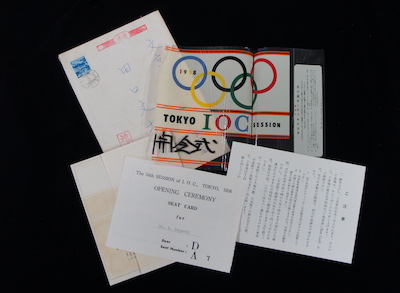

From the Bunta Taguchi archives

Bunta Taguchi was a Tokyo Imperial University graduate who served in the important position of medication general in the army. He devoted himself to swimming from an early age and later served in advisory positions with the Japan Swimming Federation, the Japan Amateur Sports Association and the Japan Amateur Athletic Federation. Taguchi left behind many materials related to the Olympics (in the University of Tokyo Archives). The badge labeled “Imperial Year 2592” and the Lion toothpaste raffle tickets were emblematic of the special atmosphere of the era. Additionally, the letter of resignation by Juichi Tsushima and Masaji Tabata displayed the resolve of these men to continue working in the interest of Olympic Games despite resigning from their posts. Together, these memorabilia help convey the enthusiasm of the men who staked their lives on the Olympics.

* This article was originally printed in Tansei 40 (Japanese language only). All information in this article is as of March 2020.