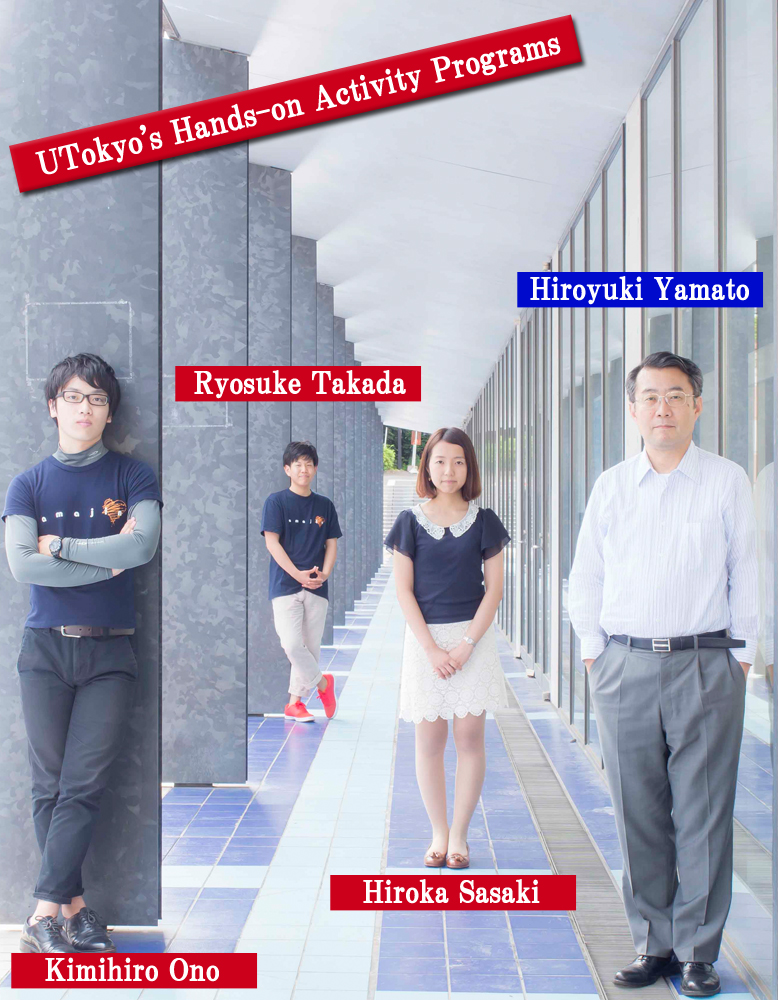

Student Discussion with One of UTokyo's Vice Presidents

These young men tutored high school students on a remote island of Shimane Prefecture for one month while this young woman received training at a prestigious school in France. What will they talk about with a vice president of the University who has promoted these special programs?

One of the initiatives that the University of Tokyo is undertaking to encourage its students to grow into tougher people is a group of short-term programs called the Hands-on Activity Programs. The objective of the programs is to allow students to be exposed to differing points of view and ways of thinking in places they do not usually get the chance to visit as students. For this article, three students who participated in these programs join one of the University's vice presidents who has been involved with planning the Hands-on Activity Programs from the beginning. They freely discuss what the programs are actually like, what the students accomplished during the programs, and the subsequent influence of the programs on their lives as students.

Participants in the “Public Preparatory School: a Project for Uncovering Issues and Solving Problems using the Okinokuni Study Center as a Platform” Program

Kimihiro Ono, fourth-year undergraduate student, Department of Integrated Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education

Ryosuke Takada, third-year undergraduate student, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering

Participant in the “Train at a Grande École and Learn from UTokyo Alumni Working in Paris” Program

Hiroka Sasaki, third-year undergraduate student, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering

Head of the Working Group for the Promotion of the Hands-on Activity Programs

Hiroyuki Yamato, Vice President and Professor, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences

Ono: For about one month in August 2013, I stayed in the town of Ama in the Oki Islands of Shimane Prefecture. This area has been dealing with a low birthrate and an aging population, which is leading to a decrease in the number of people in the town. There were so few children that the local high school was on the verge of closing at one point. As one of its initiatives to attract more people to the islands and keep the school open, the town now runs a public preparatory school called the Okinokuni Study Center. We helped to tutor the islands' high school students at that place.

Yamato: I saw something about that on TV. They said that some students came from Osaka and Kyoto to study at the high school there.

Ono: That's right. Now there are even students coming from outside of the prefecture who want to enroll in the high school. We acted as teachers for about 15 of the third-year high school students (seniors) taking summer classes there.

Takada: The Center doesn't have enough staff members, so they said it really helped them to have UTokyo students come as volunteers.

Yamato: Is there any benefit to having university students teach instead of professional educators?

Ono: Well, there aren't any universities on the islands, so students on the islands don't really feel a close connection to the concept of a university. You'll even get asked “what is a university like?” fairly often. I think that due to our being there, though, maybe students were able to become a little more familiar with universities as places they could choose to go to after graduating from high school.

Yamato: I see that your influence on the students was not just limited to teaching. What program did you participate in, Sasaki-san?

Sasaki: I took part in training at École Polytechnique, which is one of the grandes écoles, a kind of educational institution unique to France. Basically, grandes écoles are more advanced than universities and are like more exclusive versions of vocational schools. Ten of us shared rooms in dorms for 10 days while visiting international organizations and companies where graduates of the University of Tokyo were working. We got to go into places you can't normally enter, like the headquarters of UNESCO, OECD and the IEA. Before participating in the program, I didn't think that working overseas would be an option for me at all. Listening to alumni talk about their experiences, however, made the idea of working abroad a realistic one.

Yamato: The École Polytechnique is the most prestigious school among the French grandes écoles. École Polytechnique students wear military uniforms on formal occasions and walk in front of the rest of the parade on Bastille Day.

Sasaki: Yeah. The students in the dorms put on their uniforms and showed me what they looked like. When they went outside with those clothes on, they really stood out and people on the streets stared at them!

Yamato: Unlike UTokyo students, École Polytechnique students are clearly conscious of their elite status, aren't they?

Sasaki: Yes, I think so. They gave off an impression of talking on and on about nothing but their specialized area of study. It seemed like all of the students could speak over three languages, and it was required for them to do internships abroad during their summer vacation.

A second-year student who became worried around his summer break about what to do for his shinfuri (selection of fields of study) decided to go to a remote island to keep the temptation of distractions at a distance

Yamato: So, what made all of you decide to participate in the programs?

Takada: I was a second-year student facing the important transition period called shinfuri (selection of the fields of study) when I decided to participate in one of the Hands-on Activity Programs. At that time, I started to have doubts about what I wanted my specialization to be. I thought if I was at home during the summer holidays, I would run away from reality and be tempted by invitations to go out and play with my friends, indulging myself in all sorts of distractions. Thinking that I would be able to turn down these kinds of invitations if I went to a remote island for one month, I decided to apply to the program in Oki. I also have another reason. I actually participated in another one of these Hands-on Activity Programs when I was a first-year student. There was one little detail of the program which caused me a lot of trouble: “Language used: English.” The only English phrases I could really say were simple things like “good morning,” so… Although it was a meaningful two-week program where we worked hard to construct a rest house in a mountainous area in Miyagi Prefecture, I was overwhelmed by my sense of powerlessness due to my lack of English proficiency. So seeing “Language used: Japanese” in the description for the Oki program really drew me in!

Ono: A case study on Ama came up in a class I was taking in the Faculty of Education. I heard from the teacher that one of that year's Hands-on Activity Programs was going to take place in Ama, so I decided to apply for it.

Vice President Yamato specializes in industrial information systems and environment, a field concerned with the efficient management of individual and group knowledge through the use of computers and information networks. He is particularly focused on the development of on-demand bus systems. He is the President of the Japan Society of Naval Architects and Ocean Engineers.

Yamato: Where are you from, Ono-kun?

Ono: Okayama Prefecture.

Yamato: When I was a third-year undergraduate student, I participated in a one-month trainee program at a shipyard in Okayama. You see, in the past, students in the Faculty of Engineering had to do on-the-job training during their summer holidays. We made around 300 yen a day. We got academic credits for doing the training, but I wasn't able to sleep well since they didn't have air conditioners... Anyway, Sasaki-san, what were your reasons for participation?

Sasaki: I'm not sure why, but I fell in love with the Gothic architecture in the colorful city of Paris. I chose to specialize in French language during my first two years in the College of Arts and Sciences, thinking that I would be able to visit France someday. I heard about the Hands-On Activity Programs right before the application deadline, so I looked them up and saw that one of the programs was going to take place in France. I thought participating in that program would be a good opportunity for me to go to France. Also, I had heard about the grandes écoles in my French classes here at the University. Being able to see famous landmarks like the Notre Dame Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, and the Arc de Triomphe in person was a big thrill for me.

Ono: I'd like to go to France sometime, too. At the time, though, I wasn't thinking about any other program but the one in Ama.

Sasaki: I want to visit the islands, too, like you did. My grandmother lives on an island, so I go there to see her once a year. I think it'd be nice to stay on an island for a month or so, though.

Yamato: I wonder what will become of Japan's remote islands. What did you sense about Japan's future when you were on the Oki Islands?

From Okayama Prefecture. He decided to participate in the program in Ama after he came to know about the town through an undergraduate class taught by Professor Atsushi Makino of the Graduate School of Education. After returning to Tokyo, he continues to give advice via Skype to local high school students on the islands.

Ono: I think the issues that Japan will have to face from now on will materialize first on its smaller islands. With regards to these kinds of issues, things are going well enough for Ama that they were able to add another class of students to their high school. I think this kind of success is meaningful even when looking at it from a global standpoint.

Yamato: The rest depends on whether there are jobs there or not.

Ono: I agree. One particular characteristic of Ama's case is that many of the people moving to the town are from urban areas. When they come to the town, they bring in ideas and viewpoints that people in the town previously didn't have, while at the same time uncovering the wonderful old traditions of the islands. Rather than finding jobs that are already there, these people create new work on their own.

Takada: That reminds me of this person I met who was working on a rock oyster farm. At first, I took him to be a longtime islander. When I talked with him, though, I discovered that he moved to the island from the city. These kinds of migrants had assimilated so well in so many areas of island life that it sometimes surprised me.

Ono:On one hand, I believe it may be important for rural towns like Ama to bring in people from other areas. The more I think about it, though, you could also say that these towns are at the same time snatching people away from other areas.

Yamato:I think Japan can learn a lot from France, such as how to create governmental systems and other kinds of institutions. France is the country where the French Revolution took place, after all.

Sasaki: Looking at France from an educational standpoint, I felt that it was normal for people in France to have been taught from a young age to question everything. They would often immediately ask me “why,” which would drive me into a corner! I had heard that French people had a lot of pride and that they wouldn't speak to you in anything other than French, but that wasn't true at all. The only thing was, though, that they'd speak to me in English and I wouldn't be able to respond due to my lack of English ability. That made me realize that I had to work on my English.

Yamato: When I went to park in Germany a long time ago, I was moved to find a poem there by (Friedrich) Schiller that I had studied in my German language class during my first or second year at the University of Tokyo. I didn't really think anything of the poem when I had read it in the classroom, but seeing it in that park in Germany brought the poem to life for me.

Sasaki: The students in France really knew a lot about Japanese manga. They'd mention manga by Tezuka Osamu, for instance, but I wouldn't have any idea what they were talking about, which kind of bothered me. I realized then that while it's good to be interested in foreign cultures, it's important to know about the culture of one's own country, too.

The Champs-Élysées was unexpectedly filthy. Just walking on the street made my shoes dirty.

From Ehime Prefecture. She realized how important the French language was when she visited the headquarters of the OECD. She was surprised that non-Japanophiles would say “kawaii” to her and talk to her about Kyary Pamyu Pamyu.

Yamato: How did you feel about Japan when you came back?

Sasaki: I felt that Japan is an easy country to live in. Over in France, they didn't really have things like digital signs in train stations that tell you when trains are coming. In Japan, though, those kinds of things are everywhere.

Yamato: When I come back to Japan from abroad, I feel that the color of greenery in Japan is different from that in Western countries. Greenery in Western countries is bright and defined. I sometimes feel that the color of greenery in Japan is a little bit more subdued.

Sasaki: When I rode trains in France, I remember the inside of the train cars being unclean and seeing corn-on-the-cobs dropped on the floor. The Champs-Élysées was also filthy, and my shoes got really dirty after just walking on the street.

Yamato: What were the Oki Islands like?

Ono: They didn't have any convenience stores, fast-food restaurants or famous chain stores.

Takada: That being said, there were non-chain restaurants there, so it's not like we had any trouble finding places to eat.

Yamato: Did they have yachts there?

Takada: I'm not sure, but I did go out on a fishing boat with people who worked at the town office once. They invited me to go hunting for turban shells with them. I had drunk the day before, though, so the seasickness I experienced on top of my hangover wasn't very fun…

Yamato: Was there anything that surprised you about the island?

Takada: Yeah; the community was more closely knit than I expected it would be. One of the locals was a young man named Ota, an aspiring photographer who was a little older than I am. He came from outside the island to take pictures of the town since it is a genkai shūraku (marginal village), an aging community that is rapidly losing its population. Ota-san lived in an old Japanese-style house where we participants stayed during the program, and he juggled multiple jobs. For instance, sometimes he would work as a hotel bellboy, and during the peak of oyster farming season, he would help out with that, too.

Ono: Staying at Ota-san's house really allowed us to connect with many kinds of people on the island. The house didn't have a lock, so anyone could come in whenever they wanted. Locals always came over to the house and had drinking parties almost every night. Even if Ota-san stayed up until 3AM drinking, he would go to work at 5AM. That's the very image of “tough” in my mind.

Takada: Ota-san was really a free spirit. He did nothing during the day but drink, and that would put him in a really happy mood. “You mustn't kill bugs,” he would say, but at the same time, he would use mosquito killer, claiming that mosquitos were an exception.

Ono: Staying in Ota-san's house was the first time I experienced living in an environment without an air conditioner, television or flush toilet. When I came back to Tokyo, it seemed strange to me that we live such busy lives.

Yamato: In Paris, the pace of life is a little bit slower than that of Tokyo. Long vacations are the norm there, for example.

Sasaki: I heard that people in France are forced to take three weeks of vacation during the summer. When I was hearing people around me talking about taking trips to Greece with their families, it made me think that working overseas must be nice.

Ono: The Oki Islands are exactly the same in that regard. I didn't even know what a lot of the people there did for a living!

Takada: We often drank and chatted with local people at night, but wouldn't know what those people did during the day. For instance, there was some guy who wore a gas station attendant's cap, but I wondered what in the world he really did for a living.

Ono: Seeing these kinds of people with strong ambitions and desires emigrating to the islands made me think that islands could be the starting point of change in Japan. Sometimes the locals who had been living there all along would see these emigrants as people who would eventually leave the islands someday, though.

Takada: When I was there, I had mixed emotions because I knew that we would be leaving the islands, too. But being able to hear from both local islanders and transplants was a valuable experience for me. Had I talked with only one of those two groups of people, I may have only been able to hear nothing but the good things about island life. I was lucky to learn from both longtime islanders and people from outside of the islands, as they gave me a comprehensive understanding of what it was truly like to live on the islands.

Yamato: The same is true for post-disaster reconstruction projects in the Tohoku region (northeastern Japan). People who work on those projects are expected to return to where they came from in two or three years.

Ono: We are seeing some results of the efforts in Oki. However, just as people are leaving the Tohoku region like you said, there are also bound to be people who will leave those islands in the future. We came from outside of the islands to help out, but I wonder if maybe what we did just looked like brainwashing to the locals.

Yamato: Sasaki-san, let me ask you a question. Did a lot of the participants in the France program come from science backgrounds?

Sasaki: Yes, almost all of the participants this time were from the sciences, and only two people came from the humanities. When we went to the Akamonkai (UTokyo alumni) gathering in Paris, I met a person who works for (UTokyo Professor) Kengo Kuma's office in France, Kuma & Associates Europe. Once they found out that I was an architecture major, they immediately made an effort to include a visit to their office in our schedule, and I was grateful to them for that.

I've learned for the first time how to live by both relying on and being relied on by others.

Yamato: Could you tell us how your experiences through these programs changed you?

Sasaki: Seeing that it was normal for students in France to be essentially trilingual, I realized how important it was for me to at least master English. Also, I also felt like if you're going to go abroad, you should know more about your own country first. After all, when I talked with the overseas alumni, they were all able to look at Japan objectively.

From Kanagawa Prefecture. Whilst being made fun of as a “Shonan boy (surfer dude from the Shonan Coast)” by people on the islands, he became a master at doing the local kinya-monya dance. Ryosuke went to the islands again to help out with this year's program in Summer 2014.

Takada: Before visiting the island, I tended to care too much about other people's feelings. On the island, I met Ota-san and was greatly influenced by him. In addition to having aspirations, he enjoyed his everyday life to the fullest. Through getting to know him, I came to see that a lifestyle like his was also possible. I've decided to consider what I really want to do, instead of just following the well-traveled, “typical” path to happiness. I realize now that simply studying and taking classes alone will not allow me to grow into an interesting person in the future.

Yamato: I wonder what made you come to that conclusion. I know the presence of the landlord (Ota-san) was a big part of it. You might have also been influenced by the islands' natural environment, I think.

Takada: I think it's because there often wasn't anything else to do on the islands, so I had a lot of time to think. There was certainly plenty of time for me to relax and look back on the events of each day.

Ono: I had always been interested in what living in an underpopulated area was like. At the same time, though, I thought that maybe people who said that rural living was enjoyable were actually just people who couldn't make it in the city. Being on the islands for one month, however, has led me to think that people truly do enjoy living in those kinds of places. I felt the way I originally did just because I had only one way of looking at things. Also, I used to think that being able to do anything and everything by yourself meant that you were an adult. I came to realize, though, that people are able to live only after being supported by other people. I feel like I was able to understand how to live by both relying on and being relied on by others.

Yamato: From listening to your experiences, I can tell that the three of you have broadened your horizons considerably. You all put yourselves in places unfamiliar to you and became aware of the many kinds of differences between those places and the places where you were raised. I expect that you will advance further in your studies by using this knowledge which you gained through these programs. You can jump into unfamiliar locations and do these kinds of things only when you're young. At the same time, you should not forget the sincere efforts of all the people at the program locations who supported your activities. Their actions serve as proof that society in general has confidence in and expectations for UTokyo students. You have to make sure you don't betray their trust. If you can look back later and say that your experiences during the Hands-on Activity Programs were meaningful to your life, then these programs can be considered a success. It would be great if the people who supported your activities felt the same way, too. Also, it would make me happy if you all would become supporters and accept UTokyo students participating in Hands-on Activity Programs when you become older. Especially you, Takada-kun—don't you think it would be fun to welcome UTokyo students to the Oki Islands in the future?

Takada: … I'll consider that proposition when I go back to Ama this summer.

Vice President Yamato before UTokyo

Picture taken when he was a second-year high school student.

Kimihiro before UTokyo

Picture he used in his student handbook when entering high school.

Hiroka before UTokyo

Picture taken during her high school days.

Ryosuke before UTokyo

Taken when he was a third-year student at his high school's culture festival.