Carrying the Hopes of Younger Generations

-

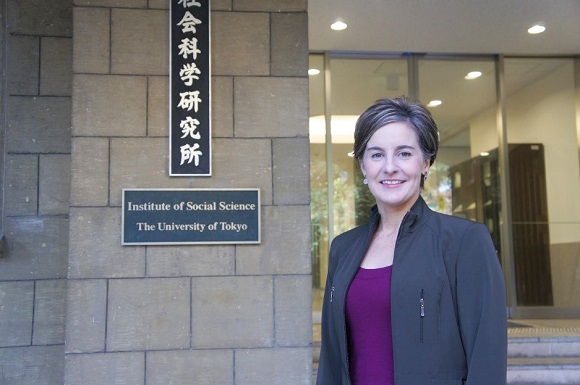

- Jackie F. Steele

- Associate Professor, Institute of Social Science

Areas of research: Political representation, feminism, diverse citizenship, Japan and Canada

Country/Region of Origin: Canada

A Lifelong Adventure that Started with a Single Japanese Class

For the last two decades, Professor Steele has used kanji for her first name: "若" ("jaku," meaning "young") and "希" ("ki," meaning "hope"). As a democratic theorist, she believes that younger generations are the hope for a more inclusive society; they are more open to social change, gender equality, and diverse families. Her kanji namesake was chosen to represent solidarity with women and social justice movements around the world. Life in Japan has brought many rewarding opportunities to stimulate Japan-Canada policy dialogues and grassroots cross-cultural conversations on these challenging issues.

From French to Japanese

I grew up in Delta, British Columbia, a beautiful sunny suburb of Vancouver. While the primary language used in British Columbia is English, both English and French are official languages in Canada. Given the importance of early exposure to second languages, in 1996, BC started offering elementary school French immersion programs. I started in Grade 6 and really enjoyed learning about francophone languages and cultures (such as Haitian, French and Québécois). In 10th grade (high school), I was curious to try another language and the class on offer happened to be Japanese. At first, I was rather shocked by the gender hierarchy conveyed through the use and expressions in both the spoken and written Japanese language. I was fascinated by the fact that Japanese is used so differently based on the gender of the speaker and listener (male or female) and depending on the age groups and social positions of the interlocutors. I was also very attracted to kanji or Chinese characters; the ability to express the conceptual meaning through at times aesthetic pictographic elements offered a rich depth that was absent from English and French.

Pursuing Japanese studies in Francophone Quebec

After graduating from high school, I wanted to immerse myself in a French-speaking environment. I spent 6 weeks in northern Quebec and then entered McGill University in Montreal, where there is a vibrant francophone multicultural vibe that is quite different from West Coast pan-Asian Vancouver. While my primary interest was political science, I also wanted to continue my Japanese language studies. I double majored in Political Science and East Asian Studies, with a thesis comparing women's equality rights under the constitutions of Canada and Japan. Having consolidated my fluency in French, after graduation I wished to be immersed in Japanese society to hear how Japanese people really spoke to one another. I applied for the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Programme to work as a Coordinator for International Relations (CIR) so that I could work in Japanese every day and experience how Japanese native speakers innovatively communicate in their own language.

One Year before the Nagano Winter Olympics

Source: Chikuma City

Source: Chikuma City

Dr. Steele was admitted to the JET Programme and came to Japan in 1997. She requested placement in a rural area so that she could immerse herself in a traditional Japanese community.

Discovering a new furusato (hometown) in Koshoku

I was assigned to live in Koshoku City (currently Chikuma City), Nagano Prefecture. At McGill, I had watched a Japanese movie about obasute, which was an ancient Japanese practice, sometimes seen in poor villages, of abandoning old women and men in remote areas to save resources for younger family members. I was surprised to learn that Koshoku City was famous for the beautiful terraced rice-fields on "Obasute" mountain; Basho had made the scene famous in a haiku poem on the beauty of the multiple reflections of the moon (“tagoto no tsuki”). This strange coincidence made me feel that I was destined to live there (laughs). I worked as a CIR in both the Financial Planning Section and the Lifelong Learning Division of the Koshoku municipal government. The mayor at the time, Mayor Miyasaka, was wonderfully open-minded and progressive. He empowered me to initiate a variety of new cross-cultural projects, from Halloween events for children to human rights-related workshops, a multicultural heritage festival, and even a gender equality course for citizens. With engaged residents, we created an independent international exchange organization that offered excellent opportunities for grassroots leadership. We converted to a legal NPO in 2014 and I was asked to serve as Vice President; I continue to work with my community today.

Participating in the Nagano Olympic Organizing Committee

Fortunately, I moved to Nagano in 1997, just one year before the Nagano Winter Olympics. Perhaps the Japanese government thought that Canadians, being so used to the cold, would have no problem surviving in Nagano's winter weather—but I am actually a “samugari” (a person sensitive to the cold) from temperate Vancouver! When the Olympics started, I was assigned to the Nagano Olympic Organizing Committee Headquarters, where I worked as a translator, interpreter and foreign media coordinator, using English, French and Japanese. I gained a lot from this experience. In fact, my entire three-year tenure as a CIR in Koshoku City Hall was really rewarding, offering a crash course in local governance and cross-cultural communication that gave me extremely valuable and practical experiences.

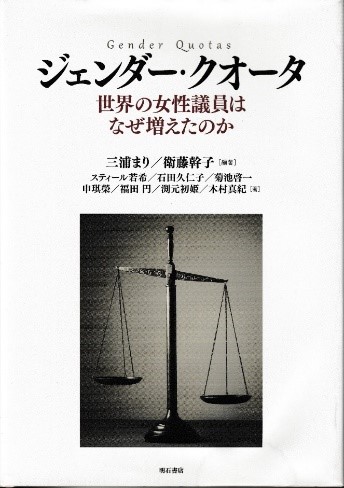

(Steele’s chapter, “Diverse Political Identities and the Potential of Quota Systems: The Japanese Electoral System in Perspective,” appeared in eds. Mari Miura and Mikiko Eto, Gender Quotas in Comparative Perspectives: Understanding the Increase in Women Representatives, Akashi Shoten, 2014.)

One Year before the Great East Japan Earthquake

Dr. Steele traveled to Tohoku University's Graduate School of Law in Sendai, Japan, to gather data for her research at the University of Ottawa on electoral systems design and women’s representation. She was hosted by Tohoku University Professor Miyoko Tsujimura. As part of her research, she interviewed senior party officials and 18 women parliamentarians. Following the completion of her PhD in 2009, she applied for a two-year JSPS postdoctoral fellowship and was again hosted by Professor Tsujimura at the Tohoku University Global Center of Excellence (GCOE) Program on the theme of “Gender Equality and Multicultural Conviviality in the Age of Globalization.”

Realizing the importance of disaster resilience

While I was at Tohoku University, I experienced the Great East Japan Earthquake with a seven-month old baby. Despite great support from my neighbours, after two days in a home without lifelines, I evacuated to the homes of my dear friends in Chikuma. This experience with extreme risk motivated me to spend the past six years focusing on the intersections of social diversity, risk governance, and disaster resilience in Japan. Disasters tend to exacerbate many human rights issues related to equality, social inclusion and access to public services. Promotion of disaster resilience is a key public policy that requires conscious feminist law reform advocacy to ensure that policy comes to grips with the diverse needs of both women and men. I am grateful for the participatory action research I have been able to pursue thanks to the generous collaboration of the Japan Women’s Network on Disaster Risk Reduction and of NPO Women’s Eye. I am grateful for support from the Institute, and also to the JSPS start-up grant that I received after my second child was born. These two stimulating projects have allowed me to track post-3.11 women’s representation through high-level law reform advocacy as well as through the grassroots leadership of young women in Tohoku.

As a small piece of advice for those who are planning to study or work at UTokyo, I would suggest giving some thought to what you will do to prepare for a large-scale natural disaster, such as an earthquake. When a disaster occurs, you cannot take anything for granted, be it buying water or food, using electricity, or accessing cell phone service to tell loved ones abroad that you are safe. Most crucial to surviving the immediate aftermath, I recommend that you take the time to get to know your neighbours and the locals in your community; they will be the first resource to help you and your family.

Drawn to UTokyo

When researching in Sendai, I was fortunate to meet Dr. Mari Osawa, a professor (currently the Director) of the Institute of Social Science at the University of Tokyo and a pioneer in the area of economics, social policy and gender. She alerted me to a position that had opened at the ISS in 2012, one year after the earthquake. I was excited about the prospect of working in a research institute in Japan that was open to critical theory and research on the politics of gender and diversity. She also informed me that UTokyo had daycare services for researchers with young children. For foreign women scholars who cannot rely on grandparents nearby to help with children, and notably in an earthquake prone country, access to childcare services at work is indispensable for risk mitigation. I hope that UTokyo will expand its childcare services so that more researchers (UTokyo mothers and fathers) can be supported to share in co-parenting responsibilities more equally.

Wearing the Two Hats of Researcher and Editor

Professor Steele's research focuses on issues related to politics, gender and diversity. She is also the Managing Editor of Social Science Japan Journal (SSJJ), published by Oxford University Press.

SSJJ’s 20th Anniversary: be our valentine?

In my capacity as Managing Editor of SSJJ, over the past five years I have worked closely with the Editor-in-Chief and editorial board members to shepherd the double-blind peer-review process, and to likewise support authors all the way through to the successful publication of their research results. I oversee the publication of two issues per year featuring original social science research on modern Japan. We just launched our twentieth issue (https://academic.oup.com/ssjj), which features a beautiful constellation of articles on irregular employment, labour stratification and gender inequality. With Oxford University Press counterparts in Tokyo, we have developed a special 20th anniversary Valentine’s campaign to shed light on the Journal’s accomplishments. Japan scholars from around the world have generously sent us their Valentine’s messages and they have nominated their favourite SSJJ articles for free download throughout our anniversary year. SSJJ plays a crucial role within the social sciences in Japan, and moreover, it is an intellectual ambassador for the University of Tokyo to Japan scholars worldwide. Twenty years on, it remains a vital interdisciplinary space that engages with new research directions and invites a common conversation on the critical debates animating contemporary Japanese society.

Working for broader recognition of the power of diversity

The mission of the Institute of Social Science is to promote democracy and peace. My main research interest is to investigate to what extent the concepts of diversity and democratic freedom are reflected within political institutions, laws, and social norms in Japan, and in comparative perspective. In particular, I am interested in democratic innovations that foster the integration and representation of diversity in decision-making bodies.

The concept of intersectionality is useful as a tool for analyzing the effectiveness of law and public policy. Unlike universal concepts of citizenship that end up really only applying to the "average" citizen or “dominant norm,” the concept of intersectionality considers the complex interactions or overlapping identity and social status that work simultaneously to limit our enjoyment of equality, social inclusion and freedom. Feminist intersectional analysis is used widely by policy-makers in Canada because it allows for rigorous analysis of the breadth of cases and circumstances that law and policy must address to be effective and responsive to a diverse population. One size does not fit all in Japan either. Through comparative research on a variety of topics (women’s married names, political recruitment and electoral systems design, gender quotas, resilience and disaster reconstruction, etc.), I have introduced (and adapted to Japan) the concepts of diversity, subjectivity, and mutual non-domination, based on insights from Canadian political theory and Canadian and Québécois practices of integration used to advance gender equality, multiculturalism, diverse citizenship and multinational democracy.

Challenges Facing Japan and UTokyo: from Principles to Practices

After twenty years of living and working predominantly in Japan, I am increasingly concerned with how painfully slow it has been for gender equality to be institutionalized as a democratic practice and social norm within universities, schools and notably within the family. From a research perspective, the lack of diversity in the Diet, in terms of both gender and generation (age group), further stifles young women’s (and young men’s) interest in politics. The dearth of women in politics in post-WWII Japan confirms the necessity of legal gender quotas (and ideally generational quotas) for all levels of electoral politics. We need a new ethical standard for political party recruitment to make gender-balanced governance a new democratic norm in Japan. A collective good that stands to diversify the views represented within all subsequent policy debates in the Diet and local assemblies, the influx of more young people and the realization of gender balance will also stimulate politics/gender research expertise in Japan and within Japan studies programs around the world. As a leading national university, I would love to see UTokyo become a beacon of hope for the younger generations and notably for young women in Japan. Gender balance in the student body, across all disciplines, and a more effective hiring strategy could ensure greater diversity among the student body and the tenured faculty members. We know that a critical mass of actors is essential to sustainable transformation of norms and workplace cultures. By developing strong practices of diversity integration, UTokyo would also become better equipped to contribute to the international research on multicultural citizenship, globalization, women’s empowerment, and inclusive decision-making (public and private), among other pressing issues facing advanced economies worldwide.

A paradigm shift in the concept of citizenship

Over the last two decades, I have actually lived in Japan longer than in Canada. It has been my second, or perhaps even my primary community of belonging. My two children were both born and are being raised in Japan. Nevertheless, I am not eligible to vote in Japan, due to my Canadian nationality of birth. Although my spouse and I work, volunteer, pay taxes and contribute to Japanese society to the best of our abilities, we are not allowed to influence the formal elections of decision-makers in the Diet or in the prefecture and city where we live. Yet, the various laws that they adopt also define and affect our lives, and the opportunities of our children. Despite being a political scientist who is deeply committed to reviving the salience of representative democracy, I have made the ironic decision of investing so many years in a country that politically disenfranchises me.

Long-term foreign residents in Japan are a reality. I do think it is time for Japan to embrace the possibility of “Japaneseness” being a political status of belonging that can also be chosen. Canada has worked to become a champion of diverse citizenship; it is still a work in progress, but one worth pursuing, I believe. It presumes that individuals can retain their nationality of birth even as they embrace and are faithful citizens of another adoptive country. Ideally, Japan would formally become open to recognizing and creating a multinational political community that fosters solidarity across the rich diversity that contributes in practice to the dynamism of contemporary Japan. Based on my experiences in Vancouver and Montreal, I firmly believe that people of various linguistic, religious, racial and ethnocultural backgrounds can work together in solidarity to build a democratically inclusive, internationally-minded and innovative society. That is the democratic project I long to see unfold in the next two decades, such that the unique diversity, creativity and voices of my own children may also become formally welcome in Japan, in a not-so-distant future.

More information on Dr. Steele's research and published works can be found on the Institute of Social Science's website at http://www.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/division/steele_e.html.

Dr. Steele's “mai-oke,” the affectionate name given to one’s personal okedo.

Dr. Steele's “mai-oke,” the affectionate name given to one’s personal okedo.Appreciating Traditional Japanese Culture

Practicing the taiko (Japanese drum)

Professor Steele is passionate about wadaiko (Japanese drumming). She first saw taiko performed in Montreal by Arashi Daiko while a university student. She was determined to play in Japan and joined Hitoeyama Daiko soon after arriving in Koshoku City. While living in Sendai, she was welcomed into Kamo Tsunamura Daiko and had three years of wonderful taiko adventures, including a performance on the fringe stage of the world-famous Earth Celebration held annually on Sado Island. The taiko shown in the picture is an okedo that was hand-made by a dear member of Kamo Tsunamura Daiko. She is excited to have found a new sensei in Kawasaki to help her improve her skills on the okedo.