令和5年度 東京大学秋季学位記授与式・卒業式 総長告辞

Address by the President of the University of Tokyo at the AY 2023 Autumn Commencement Ceremony

To all of you receiving your bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral, and professional degrees today, congratulations! On behalf of the faculty and staff of the University of Tokyo, I offer my deepest respect for your efforts and heartfelt congratulations on your achievements. I also wish to convey my gratitude and best wishes to your families, who have encouraged and supported you along the way.

The past few years that you have spent at UTokyo have been marked by global events that disrupted daily life and posed challenges for your studies and research. I am thinking especially of the COVID-19 pandemic and the international turmoil sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the business world, the abbreviation VUCA, standing for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity is used to describe unpredictable times like ours.

As you set out from UTokyo into the wider world to pursue your careers, you may indeed encounter unexpected disasters, irrational conflicts, and sudden misfortunes that threaten to overwhelm you. So before you take your next step, I would like to spend a few minutes now reflecting on how you can face such problems and continue to move ahead.

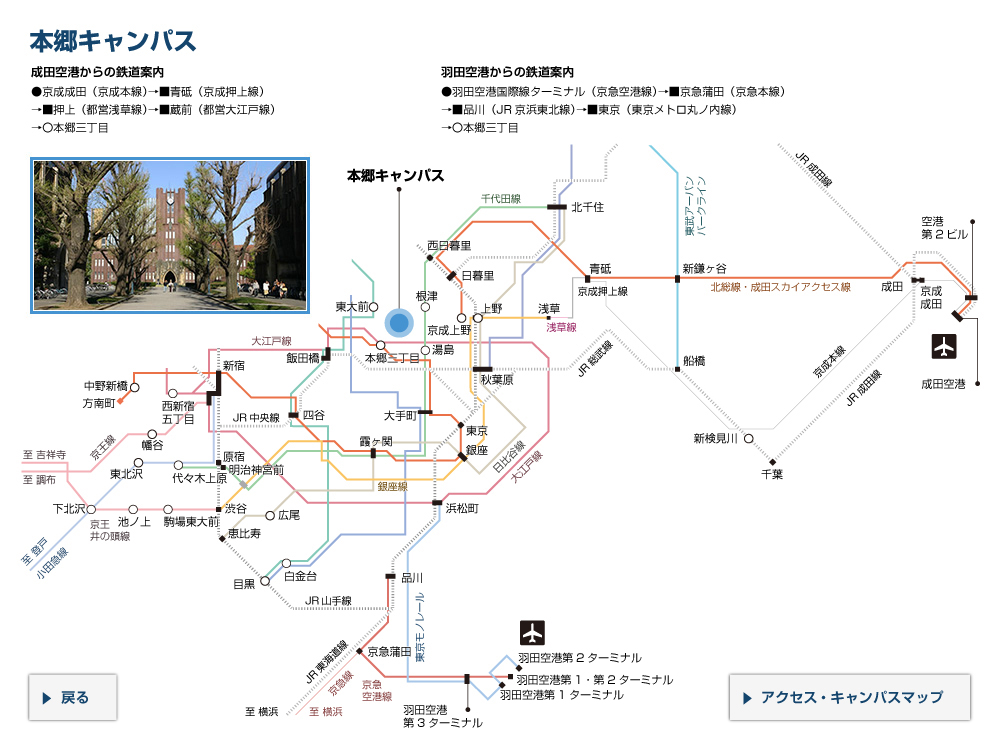

Four years from now, UTokyo will mark the 150th anniversary of our founding in 1877. The iconic Akamon Gate which you all know well is a vestige of the Hongo Campus’s past as the estate of the Maeda clan during the Edo period. That gate is now being renovated in preparation for the anniversary. But aside from the brick wall along Hongo-dori Avenue, which dates from around 1900; the old library’s custodians’ office and book bindery from 1910 at today’s Communication Center; and the Main Gate, which was rebuilt in 1912—almost nothing remains on campus from the Meiji period, which ended in 1912. The reason is the Great Kanto Earthquake, which struck exactly one hundred years ago, on September 1, 1923, at 11:58 in the morning. That quake set off fires that destroyed one-third of the buildings on this campus.

How did people respond to that disaster then?

Well, the damage from the earthquake was made much worse by the fire. Because the quake struck around lunchtime, when people had fires lit for cooking, flames broke out across Tokyo. Both the main quake and the many aftershocks delayed firefighting efforts, and a firestorm arose that took a full two days to contain. As we saw in the recent tragedy in Lahaina on the island of Maui in Hawaii, it is indeed very difficult to confine the spread of fire even now. That afternoon, a gigantic cloud could be seen in the sky from all over Tokyo. At first, people did not realize that the smoke came from the burning city. Rumors spread that it was from an erupting volcano or an explosion at a gunpowder warehouse.

The fire spreading north from the city center was stopped at Kasuga-dori Avenue near Hongo Sanchome. In those days, the part of today’s Hongo Campus south of Akamon was still owned by the Maeda clan. During the Edo period, they had maintained their own fire brigade called the Kaga Tobi. On September 1, the head of the clan, Toshinari Maeda, encouraged people in the area to fight the fires, and together they were able to keep the flames from reaching the University.

However, other fires broke out in three locations on campus after chemical storage cabinets fell over in laboratories of the Faculty of Engineering and the Faculty of Medicine. Especially devastating was the fire at the Faculty of Medicine’s laboratory for medical chemistry near Akamon. Fanned by the strong winds from the south drawn by a typhoon in the Sea of Japan, it spread north to the library and to the classroom buildings of the law, literature, and economics faculties. It ended up engulfing all the major buildings around the Yasuda Auditorium where we are today, including the octagonal lecture hall of the Faculty of Law and the Sanjo Conference Hall next to the Sanshiro Ike pond. Because the walls alongside the buildings had fallen in the earthquake, the flames not only entered through damaged upper floors on one side but also created drafts that spread the fire to adjacent structures on the other. The result was a wide-scale conflagration.

The university library burned to the ground. Overall, the university lost some 760,000 volumes. A writer named Yaeko Nogami who lived in Nippori later wrote an essay with the evocative title “The Burning Past.” In it, she described seeing charred pieces of paper with Latin words printed on them raining down on the small park in Nishi Nippori where she had taken refuge. She was horrified to realize that the treasure trove of knowledge at Tokyo Imperial University was ablaze.

In the wake of that great calamity, the University received help from around the world. Just a couple of weeks later, the League of Nations in Geneva adopted a resolution to facilitate international cooperation for rebuilding the library’s collection. The swiftness of that response was partly due to similar efforts nearly a decade earlier by an international coalition, including Japan, to help restore the library at the University of Leuven in Belgium after it was destroyed in the First World War. Thus there already existed momentum for the world to join hands to protect storehouses of knowledge, and Japan had been part of that international initiative.

Our library benefited from much generous support. The British Academy collected donations from publishers and sent us around 70,000 volumes, including 187 rare books illuminating the history of printing. The nations providing aid included, in alphabetical order by their names then, Belgium, China, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Siam, the Soviet Union, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States, plus donations from organizations and individuals in 21 other countries, representing a total of 35 nations.

Donations poured in from within Japan as well. Marquis Yorimichi Tokugawa of the Kishu Tokugawa family donated 96,000 items from his Nanki Collection that had been available to the public at his residence. The library also received books on Western arts and crafts that had been collected by the photographer Koreaki Kamei during his study in Germany, and the family of the writer Ogai Mori, who had died the previous year, donated his books as well. Together with collections bought using monetary donations, the gifts infused the reconstituted University of Tokyo Library with a new diversity.

The problem was where to put the books. The national government was trying to deal with an unprecedented disaster and had no money left over for a university library. But the American businessman John D. Rockefeller Jr. stepped forward with an unconditional offer of 4 million yen. In today’s currency, that would be about 6 to 10 billion yen. Rockefeller’s donation funded construction of the General Library building that you know and use today.

Donations were thus an invaluable resource for recovery from disaster. The University of Tokyo will always remember the generosity of everyone who helped us rebuild from that earthquake and fire a century ago. I would like to take this opportunity to express our profound gratitude once again.

Now, what did that disaster a hundred years ago mean for UTokyo?

First of all, by doing research on earthquakes and pursuing ways to mitigate disaster damage, the University realized that contributing to a safer, more secure society was an important part of our mission.

Thus, in 1925, two years after the Great Kanto Earthquake, our Earthquake Research Institute was established. Initially focused on pursuing the science behind earthquakes and on disaster mitigation, the institute later expanded into studying volcanic phenomena and the dynamics of the Earth’s interior. Seismic and volcanic activity were later discovered to be deeply linked to the Earth’s overall activity through the theory of plate tectonics that emerged in the late 1960s. That theory explains the movement of the Earth’s crust based on the interaction of a dozen-odd plates covering our planet’s surface.

One of my own research fields is underwater technology. I have studied underwater robots for deep sea exploration. At first glance, underwater technology might seem unrelated to earthquakes. But I myself have the experience of participating in a scientific cruise in Okinawa to survey the traces of faults from the Great Yaeyama Earthquake and Tsunami of 1771 by a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV.

The Earth’s crust is, in fact, thinner under the ocean than on land, so undersea drilling is an effective way to investigate plate tectonics. In 1961, the Mohole project was launched by the United States to drill through the crust into the mantle. That effort later developed into today’s International Ocean Discovery Program. Japan has contributed to that program by providing the deep-sea scientific drilling vessel Chikyu for boring deeply in zones where major earthquakes occur.

Knowledge about earthquakes comes not only from direct observation and experiments. It is also important to read historical documents and inscriptions. Major quakes in Japan were recorded more than a millennium ago in texts, paintings, and stone monuments, but little of that information was being applied to seismology. Now, through the interdisciplinary efforts of the Collaborative Research Organization for Historical Materials on Earthquakes and Volcanoes under two of our research institutes, the Historiographical Institute and the Earthquake Research Institute, many types of information are being integrated, collected, and correlated to construct new hypotheses. This is an excellent example of collaboration between the sciences and the humanities.

This year’s intense heat and heavy rains have brought home vividly how disaster can encroach on our daily lives. Against the backdrop of global warming, we have recently seen an increase in extreme weather events as well as wildfires, floods, and droughts. Just as plate tectonics provide a unified framework for understanding earthquakes, we need to think about individual weather-related events by trying to understand the mechanisms behind the fluctuations in the oceans and atmosphere on a global scale.

Thus, a century ago, the Great Kanto Earthquake inspired UTokyo to pursue both applied and theoretical research, to find links between different disciplines, and to expand globally the depth and breadth of our intellectual inquiry for both research and education.

A second lesson of that earthquake came from the widespread reconstruction support we received from around the world. We realized anew the importance and effectiveness of building connections throughout society based on empathy among people.

We continue to cooperate today with research institutions nationwide and throughout the world on preventing and mitigating disasters of all kinds. While it is still very difficult to forecast when earthquakes will occur, a nationwide network of seismometers installed in the wake of the 1995 Kobe earthquake now enables early warning when an earthquake strikes. You’ve probably heard those warnings on mobile phones just before the shaking begins.

To minimize the loss of life, it’s also important to predict the arrival of tsunamis. Japan has been a pioneer in research on rapidly detecting, measuring, and forecasting tsunamis, and we have helped to build observation networks around the world. One such network, called DONET, runs along the submarine trench called the Nankai Trough south of the main Japanese islands of Honshu and Shikoku. That network enables real-time monitoring of earthquakes and tsunamis, and it is also used for early warnings. I used to be a part of the panel of experts for the first DONET system installation operated by JAMSTEC (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology).

The UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission is now building a tsunami forecast system for the entire world. The goal is to have all coastal communities tsunami-ready by the year 2030 so that the lives and property of the residents can be protected. This past June, Professor Yutaka Michida of our Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute was appointed the chairperson of that commission. He is the first Japanese person to hold that job, and we at UTokyo are very happy and proud about that.

Another lesson from disasters has been the importance of human connections and mutual aid. Right after the 1923 earthquake, our maintenance department set up temporary shelters and water and sanitation facilities for people who had evacuated onto campus. The Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital treated people who were injured or sick, and the Faculty of Science quickly set up a relief station at the Botanical Garden. Especially admirable were the student volunteers. They organized relief efforts and tirelessly prepared and distributed food to people taking shelter on campus and in Ueno Park. Their activities marked the beginning of volunteer work by students during disasters in Japan. Even today, researchers studying social business initiatives note the importance of the work pioneered by those students in the early 1920s.

A third major insight from the Great Kanto Earthquake was how vital information is during times of crisis.

The harm from natural disasters comes not only from the earthquakes, fires, or floods themselves. It may be hard to believe now, but in the wake of that 1923 earthquake groundless rumors ran rampant. There were claims of arson, bombings, poisonings, and military attacks. Even official bulletins and newspapers spread unconfirmed rumors. A great tragedy resulted: assaults and murders that targeted the many Koreans living in Japan at the time. That horrible experience reminds us that we continue to face serious issues involving information. Those include the surfacing of the conscious and unconscious prejudices present in everyday life; the specific challenges of urban and online spaces filled with people who are strangers to each other; and the reckless propagation of inflammatory explanations.

In 2011, after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant also led to many false rumors, this time about radiation. While social media can be powerful tools for communication during disasters, they also represent a serious problem for society, because they allow anyone to spread inaccurate information and to amplify irrational hostility. A pressing issue for us today is figuring out how to share needed information accurately and not to be misled by false rumors, especially during times of uncertainty and when communication systems are not functioning properly.

The University of Tokyo has long recognized the need for academic research on media. In 1927, a library of newspapers and magazines from the Meiji period was set up in the Faculty of Law, and in 1929 a research department for journalism studies was established in the Faculty of Letters. After the war, that journalism department became the Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies. Awareness of the importance of information in our society continued to grow, and in 2004 that institute became part of the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, or Joho Gakkan.

The wide-ranging collaborative research that had been conducted on disaster information continues today at the Center for Integrated Disaster Information Research, or CIDIR, in Joho Gakkan. CIDIR was founded jointly with the Earthquake Research Institute and the Institute of Industrial Science.

Let’s think a bit more about what UTokyo learned from the Great Kanto Earthquake a century ago.

The twin tragedies of that disaster and of the harmful rumors highlighted the importance of research both on earthquakes and on information. The burning of the library was a great misfortune, but it also drew in help and cooperation from around the world. That support made us appreciate even more the goodwill of others, and we remain extremely grateful. We also felt even more strongly that universities have a responsibility to confront the issues facing society. By searching for underlying mechanisms and by identifying basic principles, we can help lead the way to practical solutions for real-world problems. It was also a great discovery for us to realize that innovative new solutions emerge when researchers with diverse expertise cooperate and collaborate across disciplinary boundaries.

These realizations apply not only to disaster research but universally, to whatever challenges may await us. No matter what future you pursue or where you decide to live, I hope that each of you will keep learning for the rest of your life. Our abilities as individuals are limited. But let us never forget the broader connections that underlie the areas we specialize in. When you follow those connections to seek new perspectives, you may uncover innovative solutions to whatever problems you face. And even more important than just learning more, you will also be able to form connections and interact with other people who have similar interests and concerns. That is where you will find the greatest meaning in life.

So please keep this all in mind as you set sail out onto the open ocean that lies before you today. I wish every one of you the greatest success. Congratulations once again.

FUJII Teruo

President

The University of Tokyo

September 22, 2023

(和文)令和5年度 東京大学秋季学位記授与式・卒業式 総長告辞

本日ここに、学士、修士、博士、あるいは専門職の学位記を受けとられるみなさん、おめでとうございます。その努力に深い敬意を表し、東京大学教職員を代表して、心からお祝いを申し上げます。そして、みなさんをこれまで励まし支えてくださったご家族の方々にも、お祝いと感謝の気持ちをお伝えしたいと思います。

みなさんが東京大学で過ごしたこの数年間は、新型コロナウイルスのパンデミックや、ロシアのウクライナ侵攻に端を発した国際情勢の混迷など、地球規模の大きな事件が日常を変え、大学でのみなさんの学びや探究にも、さまざまな困難が生じたのではないでしょうか。「Volatility:変動性」「Uncertainty:不確実性」「Complexity:複雑性」「Ambiguity:曖昧性」の頭文字をとって、「VUCA」という言葉がビジネスシーンなどで使われ、予測不可能な未来が頻繁に語られるようになりました。

本日、東京大学を巣立って世界でみなさんが活躍していくなかで、突然の災害や、理不尽な紛争、あるいは予想もしなかった不運な出来事に巻き込まれることがあるかもしれません。そうしたとき、人はどうその不幸と向かい合い、いかに進んでいったらよいのか、ここで少し考えてみたいと思います。

東京大学は、1877年の大学創設から、あと4年で150周年を迎えます。みなさんもよくご存知の赤門は、この本郷キャンパスが江戸時代の大名前田家の屋敷地であった名残で、現在、記念事業の一つとして改修作業を進めています。その一方で、明治時代の建造物は、1900年前後に整備された本郷通りのレンガ塀、1910年に建てられた旧図書館の用務員室兼製本所(現在の東京大学コミュニケーションセンター)、1912年に建て替えられた正門などを除き、ほとんど残っていません。その理由は、今からちょうど100年前、1923年9月1日午前11時58分に起こった大正関東地震です。その火災で本郷キャンパスは建物面積の3分の1が焼失しました。

この災害にどう向き合ってきたか、そこを振り返ってみましょう。

関東大震災の被害を大きくしたのは、火災でした。ちょうど昼食時で火が多く使われていたため、東京のあちこちから出火します。本震と余震が立て続けに起こって消火活動もままならないなか火災旋風が起こり、延焼の鎮火まで丸2日もかかりました。直近のマウイ島の山火事によるラハイナの惨事からもわかるように、延焼を食い止めるのは今でも難しいことなのです。地震の日に、巨大な雲が空に現れて東京のどこからも見えたそうですが、人びとはそれが大規模な都市火災から生じたものだとすぐには理解できず、火山の噴煙だとか火薬庫の爆発ではないかとか、噂しあっていたといいます。

都心の火災の北への延焼は、本郷三丁目の春日通りで食い止められました。当時、現在の本郷キャンパスの赤門より南側はまだ、江戸時代には加賀鳶と呼ばれた消防集団を抱えていた前田侯爵家の屋敷でした。その前田家の当主、前田利為(としなり)が集まった人びとを指揮して活躍し、北側にあった東京大学は延焼を免れます。

しかし、構内の工学部と医学部の教室にあった薬品棚の崩壊から、学内3ヶ所で火災が発生しました。とりわけ、当時赤門近くにあった医学部医化学教室に発した火災は、折からの激しい南風に煽られて、北側の図書館や法文経教室に燃え移り、法学部の八角講堂や三四郎池脇の山上会議所など、今みなさんがいる安田講堂まわりの主要な建築群を焼いてしまいます。地震で建物の脇の壁が崩れたため、火は二階の壊れた部分から入っただけでなく、強い風で気流を生じて他の端から次の建物に炎を吹き付ける役割を果たしたことが、広範囲延焼のメカニズムだったと報告されています。

図書館は全焼し、全学で76万冊の蔵書が失われました。当時、日暮里に住んでいた作家の野上彌生子が「燃える過去」という印象深いタイトルのエッセイで、避難していた西日暮里の小さな公園に降ってきた燃えかすに、ラテン語の書かれた焦げた切れ端があり、東京帝国大学の「知識の宝庫」が燃えていることを知って戦慄を覚えた、と書いています。

この大災害に、世界中から援助の手が差し伸べられました。半月後にはジュネーブの国際連盟で、図書の蒐集を国際的に援助する決議がなされます。この迅速さの背景には、その10年ほど前の第一次世界大戦の空襲でのベルギーのルーヴェン大学図書館の炎上に対し、日本を含む「国際連盟」加盟国が始めていた復興事業があります。世界が手を取り合って知の拠点を守ろうという機運が既に存在し、日本はその国際協力の輪のなかに入っていたのです。

東京大学図書館も、たくさんの支援をいただきました。イギリス学士院は出版社からの寄贈書を取りまとめ、印刷史を彩る貴重書187点を含めた約7万冊を送付してくれました。支援を寄せていただいた国は、アルファベット順に当時の国名で、ベルギー、中華民国、フランス、ドイツ、ギリシャ、イタリア、オランダ、シャム、ソビエト連邦、スペイン、スウェーデン、スイス、アメリカ合衆国、さらに機関や個人が寄付した21か国を合わせて、35か国にのぼります。

国内からの寄贈も相次ぎ、紀州徳川家の当主徳川頼倫(よりみち)侯爵が自邸敷地で公開していた私設図書館「南葵(なんき)文庫」の9万6000点をはじめ、津和野の亀井茲明(これあき)がドイツ留学中に集めた西洋美術・工芸関係書や、震災の前年に亡くなった森鷗外の蔵書が遺族から寄贈され、その他の寄付金での購入コレクションを含めて東京大学の再建された図書館の蔵書に、新たな多様性が生まれていきます。

問題は、これらの書物を収めるべき図書館の建物でした。未曾有の災害後ということもあり、国の予算はなかなか大学図書館にまで回りません。そこへ無条件での400万円(現在の貨幣価値で60億円とも100億円ともいわれます)の寄贈を申し出てくれたのが、米国の実業家ジョン・ロックフェラー・ジュニア氏です。この寄付金によって、現在みなさんが親しみ、活用している総合図書館が建設されたのです。

災害からの恢復にとって、寄付はかけがえのない貴重な資本でした。100年前の震災からの復興に際し、支援していただいた方々のご厚意を、東京大学は忘れません。この場を借りまして、改めて心より感謝を申し上げたいと思います。

さて、100年前のこの不幸な災害は、東京大学に何をもたらしたのでしょうか。

第一に、震災後の東京大学が地震の学理を追究し、災害軽減に関する研究を推し進めたのは、安全で安心できる社会の実現への貢献が、大学の大きな使命の一つとして浮かび上がってきたからです。

そのために震災2年後の1925年に、東京大学に地震研究所が設置されました。当初は地震の学理の追究と震災予防に全力を注いでいましたが、のちには火山噴火現象の解明や、地球内部のダイナミクスを包括的に研究していきます。地震や噴火が、1960年代後半に登場したプレートテクトニクス理論(地球の表層を覆う十数枚のプレートの独自の動きを総合して地殻変動を説明する理論)によって、地球全体の活動と深く結び付いていることがわかってきたからです。

私の専門分野は海中工学で、深海を調べる海中ロボットの研究をしてきました。一見、地震には関係なさそうですが、私自身も、八重山地震及び津波をもたらした断層の痕跡を、沖縄の海で無人潜水機を用いて観測する調査航海に参加したことがあります。

地殻は大陸よりも海底の方が薄いため、プレートテクトニクス理論を実証するには、実は海底の掘削調査が極めて有効です。1961年にアメリカで始まった、地球の地殻を貫いてマントルとの境界面まで掘削するモホール計画の内実は、現在の国際深海科学掘削計画(IODP)へと継承され、そのなかで日本は、日本は巨大地震発生域への大深度掘削を目標とする地球深部探査船「ちきゅう」を建造するという役割を果たしました。

地震のデータは直接の観測や実験だけではなく、文書史料や碑文などの解読からも得られます。日本では千年以上前からの過去の大地震が文字に記され、絵に描かれ、石に刻まれていますが、その記録の多くは地震研究に活かされていません。しかし東日本大震災の教訓を受けて立ちあげた地震火山史料連携研究機構では、地震研究所と史料編纂所が協同してさまざまなデータを統合し、蓄積し、関連付けていくことで、そこから新たな仮説を構築する文理融合の研究を進めています。

今年の猛暑や豪雨は、まさに日常の間近に迫る災害を感じさせるものでした。近年、多発している極端な気象現象や、山火事や洪水や渇水などの事件の背景には、地球規模の温暖化の進行があります。地震災害におけるプレートテクトニクス理論と同じように、ここでも個別の災害を見渡し、地球規模の海洋と大気の変動のメカニズムを探究する必要があります。

100年前の関東大震災は、応用的研究と学理的研究の両方を究め、さまざまな学問を結び付けて、研究教育における学知の厚みや深さを地球規模に拡張していく責任を、大学に自覚させたのです。

第二に、世界から広く寄せられた復興支援に象徴されるように、さまざまな人びとの共感を軸に、社会に拡がる多くの力を繋ぎ合わせいくことの大切さと力強さを学んだことも、一つの遺産だと思います。

今もさまざまな災害に対して、全国、全世界の研究機関と協力して、防災・減災への取り組みが進んでいます。正確な地震予知がいまだ困難である一方で、1995年の阪神・淡路大震災などを契機に、全国に地震観測網や震度計などが整備され、それをもとに、緊急地震速報が生まれました。強い揺れが来る前に携帯電話が一斉に鳴るのを、みなさんもおそらく聞いたことがあるでしょう。

津波の到達予測は、人命の被害を少なくする上で、さらに大きな意味を持ちます。日本は世界に先駆けて、その検知・測定・予測に関する研究を発達させ、観測のネットワークの構築に貢献しました。たとえば南海トラフに敷設されたDONETは、地震津波の高精度リアルタイム観測を可能にし、これは緊急地震速報にも利用されています。私も、最初のDONETの敷設際に、海洋開発研究機構の専門家チームの一員として携わっていました。

そして現在、ユネスコ政府間海洋学委員会(IOC-UNESCO)は世界全体で津波予報システムを構築し、2030年までに世界中のすべての沿岸コミュニティーで津波から生命や財産を守る準備を進める“Tsunami Readyプログラム”を推進しています。今年6月、このIOC-UNESCOの議長に、日本人として初めて本学大気海洋研究所の道田豊教授が選出されたことは、東京大学にとってうれしく誇らしいニュースでした。

人と人との繋がりの大切さ、助け合いの重要性も、災害からの教訓の一つでしょう。関東大震災の当時、構内に避難してきた罹災者のために営繕課は仮設住宅や給水設備やトイレなどを設置し、医学部や附属病院は負傷者や発病者を救護し、理学部は植物園に急設救護所を設けました。素晴らしかったのは、学生たちの自主的な活躍でしょう。学生救護団が組織され、大学構内や上野公園への避難者たちに食糧の手配や配給を行うなど献身的に活動しました。これは日本における震災時の学生ボランティアの始まりともいえる出来事で、こうした活動の意義は、現代における社会貢献を目指すソーシャルビジネス(社会的企業)の研究のなかでも注目されています。

第三に、人間社会において情報が果たす役割の重要性が、危機状況においてクローズアップされたことも、関東大震災の大きな教訓です。

人間が向かい合う災害は、地震や火災や洪水などの自然現象だけではありません。関東大震災では、信じられないことに「放火」や「爆弾」や「毒薬」の、あるいは「襲撃」をめぐる流言蜚語が飛び交い、公報や新聞までもが不確実な情報を拡散し、そのなかで当時日本に多く来住していた朝鮮人に対する暴行・虐殺という悲劇が起きました。そのことは、日常のなかに潜む意識的・無意識的な偏見の噴出、未知の人間たちが多く集まる都市空間特有の困難、「炎上」ともいうべき無責任な解釈の暴走など、私たちに情報をめぐる深刻な問題を提起しています。

東日本大震災でも、福島第一原子力発電所のメルトダウンが起こったことで、放射性物質をめぐるさまざまな誤った情報が流れました。SNSは災害の際のコミュニケーションにとって力強いツールとなる一方で、誰もが誤った情報を発信でき、理不尽な攻撃性を昂進しうるという深刻な問題点を抱えています。危機状態の不安のなかで、あるいは情報インフラの機能不全のなかで、いかに必要で正しい情報を共有し、誤った情報に惑わされずに行動しうるか。それは、現代のわれわれの課題でもあるのです。

東京大学が、1927年に法学部に明治新聞雑誌文庫を開き、1929年に文学部に新聞研究室を設置したのも、マスメディアの学術的な研究拠点が必要だと認識していたからです。新聞研究室は戦後には独立の新聞研究所となり、情報の重要性が社会的に強く認識されるなかで、2004年には情報学環へと統合されます。

災害情報に関する共同研究の蓄積は、情報学環の総合防災情報研究センター(CIDIR)へと継承され、生産技術研究所とも連携しつつ、総合的な防災情報研究を進めています。

さて、東京大学は100年前の関東大震災から何を学んだのか、少し別な角度から整理してみましょう。

震災の惨状と流言の悲劇は、「地震」と「情報」の研究の必要を浮かびあがらせました。図書館焼失の不幸は、世界からの支援と協力に触れる機会となり、その厚志への感謝とともに、私たちの人間の「連携」の力を実感させました。そして社会が要請する問題解決に対し、大学が真摯に取り組む公共的な責任を有することも自覚されたのだと思います。もちろん、具体的で個別の問題を現実的に解決するためには、その背後にあるグローバルなメカニズムにまで視野を広げ、基礎にある学理の全体を理解し探究することが必要です。そして、さまざまな専門知の研究者たちが分野横断的に連携し、協力することを通じて、新たな解決のイノベーションが生まれることも、大きな発見でした。

これは災害研究のみならず、さまざまな困難に対して、普遍的に当てはまることかもしれません。みなさんがどんな未来に向かい合い、どこで生きて行くにせよ、学び続けることをやめないでください。一人の人間の能力には限界があります。自分の専門とする事象だけでなく、その根底にある大きな連関を見落とさないようにしてください。そこから見直すことで、当該の問題への新たな解き口が見つかるだけではありません。同じ興味関心で繋がる人の数が飛躍的に増加し、未知の多様な人びととの関わりが開かれるからです。そこに大きな意味があるのです。

どうかそのことを心に留めて、今、みなさんの目の前に広がる大海原へ船出してください。幸運を祈ります。卒業、修了、まことにおめでとうございます。

令和5(2023)年9月22日

東京大学総長

藤井 輝夫

関連リンク

- カテゴリナビ