令和3年度東京大学大学院入学式 祝辞(スウェーデン王立科学アカデミー元会長 Svante Lindqvist 様)

令和3年度東京大学大学院入学式 祝辞

President Fujii, Distinguished Faculty, incoming graduate students, proud parents and friends,

First I would like to thank the President, Professor Fujii, and the Members of the Executive Board for bestowing upon me the honour of addressing you, the incoming graduate students.

The Past, Present and Future; these are the three categories of our life. Today, as indeed you should be, you are consumed by thoughts of the Present, the first day of the rest of your lives – the day on which you embark on further academic education. And your thoughts may also be on your hopes for the Future.

But standing at this crossroads between the Present and the Future, as you are, should not make you forget the Past. You should remember your parents, family and friends; all those who have helped you reach this moment. In particular, you should be grateful to your parents, grandparents and other family members for their support and encouragement during your childhood and prior education.

Maybe you should also dedicate a thought to a teacher whom you remember from your school days? You see, when we established the Nobel Museum in Stockholm, we discovered that there was one thing that all Nobel Laureates had in common, regardless of their field – be it science, literature, economics or politics. And this is something that I believe is also true for most successful people.

Namely that they had a teacher at the age of around 12 or 14 – in junior high school or middle school – who had a great impact on them, and whom they still remembered with gratitude and affection. I am certain that most of you remember such a teacher. Send a thought of gratitude to him or her today! They are one of the reasons why you are here today.

The first Japanese Nobel Laureate Hideki Yukawa has written a fascinating autobiography, Tabibito (“The Traveller”). Here Yukawa-sensei describes his life and intellectual development from early childhood until the publication in 1935 of his famous article predicting the pi meson.

A decisive influence on the young Yukawa – who was then in his fourth year of middle school – was the visit of Albert Einstein to Japan in 1922. Einstein’s much publicised visit sparked the beginning of Yukawa’s interest in theoretical physics.

When Yukawa was about to graduate from university, he was filled with misgivings about his future, and even considered withdrawing to a nearby temple to become a priest. But after graduation, Yukawa entirely forgot those thoughts. He wrote:

”Looking back over my whole life of research, I view the three years after graduation as providing an extremely valuable foundation. The competitive swimmer glides under water for a brief interval after he has dived – it was that kind of a preparatory period for me.”

A long dive! And this is what you will embark upon today. A unique period in life when you can submerge yourself in new knowledge until the day when you surface again to meet the outer world.

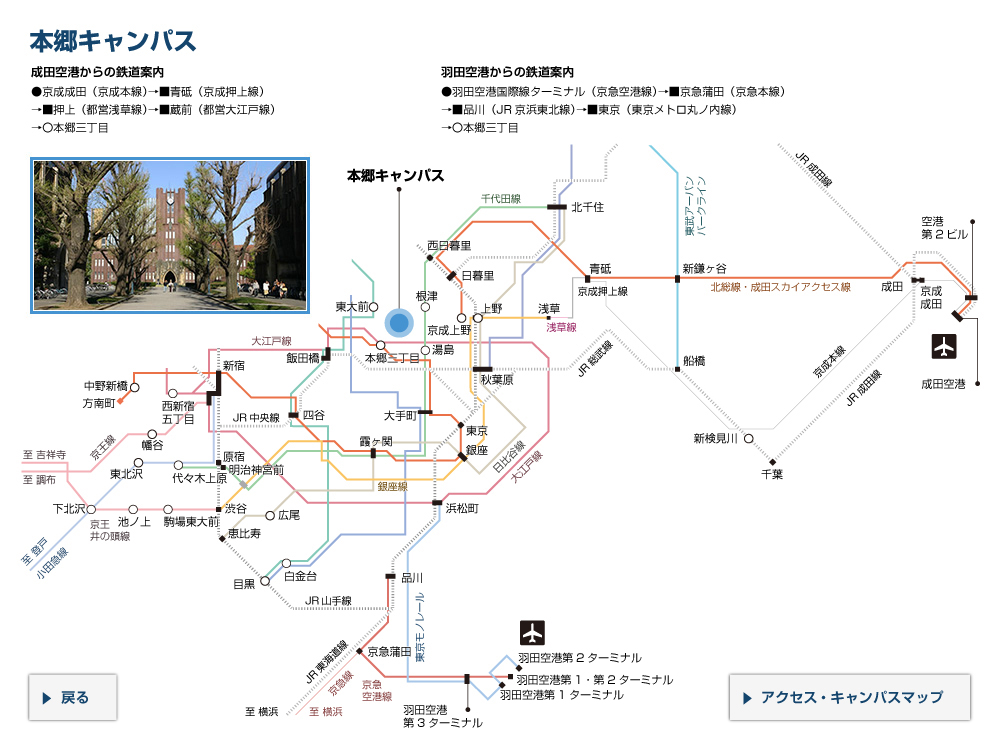

Two years ago I had the honour of teaching a course at the University of Tokyo’s Komaba campus. The students were excellent, but it was almost impossible to get them to speak in class. It didn’t help that I reminded them that English was also a foreign language to me. Were they afraid to make mistakes and lose the respect of the other students in the class? I certainly felt it was a great pity that they didn’t have the courage to speak up.

It has been said that those who are not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life. Or as Albert Einstein once said: ”A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new”. Steve Jobs – the late co-founder, CEO and Chairman of Apple – said something similar:

”Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't be trapped by dogma - which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.”

I would like to follow the advice of Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs; that is to attempt to be courageous enough to take the risk of trying something new; following my heart and intuition. So, I will read a haiku to you. A haiku that I have written and dedicated to you – to you, all the incoming students attending this ceremony here today.

Now, if this isn’t courageous, I don’t know what is!

That is to say, that a gaikokujin like me, trained originally in engineering physics, makes an attempt to bungle in the ancient art of Japanese haiku. In front of several thousand students. And not only that: in front of a faculty in which there are many learned men of letters; all well acquainted with haiku, chōka, tanka and other forms of traditional Japanese poetry.

This will also prove another of my points. That failure is not quite as dangerous as it may seem – what is more important is having the courage to try. I mean, what could possibly happen to me if you think it’s a lousy haiku? Perhaps you’ll call me a fool for trying? But what would be the consequences of that for me? Well, I would certainly lose your respect, but I would on the other hand – no matter what the outcome – be able to take comfort in the fact that I dared to try something new in the spirit of Albert Einstein.

So, here goes:

In gusts of spring rain

students sharpen their pencils

windows blow ajar

A good haiku, as you may know, doesn’t need – and shouldn’t have – an explanation. It should be intrinsically sufficient, independent of context. The feelings and emotions it evokes in the listener or the reader are its very essence. It is not to be explained, only experienced. But since my haiku doesn’t make the presumption of being “A Good Haiku” I will explain it to you, line by line.

The first line, ”In gusts of spring rain”, is, of course, a seasonal reference to spring; a time when plants begin to develop and grow. Here it alludes more specifically to the 12th of April, today, the beginning of a new term and the beginning of your post-graduate education. A time when you, too, hopefully will begin to develop and grow.

The second line, ”students sharpen their pencils”, refers to you, the students at Todai. I am aware that few – if any – of you engage in the old writing technique involving graphite pencils (those that need to be sharpened regularly). But here it is used metaphorically, implying that you will be alert and try to assimilate all the new things that you will learn in graduate school. But it is also a reminder that you should not just uncritically accept everything you will be taught. No, you should also use your sharpened pencils to make notes of your own thoughts and ideas – even if these are in opposition to, or contrary, to what you are being taught.

And finally, the third line, ”windows blow ajar”, is an allusion to the rainy winds of spring in the first line. The windows that blow ajar are the windows of your classrooms and lecture halls. They are as of today blown open so that you can learn new things from a greater world of knowledge; a world of knowledge that is more profound than anything you have been taught before. And you will have the good fortune of having the distinguished faculty at the University of Tokyo to show and explain this new world to you; to guide you through this maze of human knowledge.

In these exceptional times – during this pandemic of Covid-19 – I would like to add a few more words.

Maybe you feel that you have been unlucky? That you have had the bad luck to begin your post-graduate studies at a time when the educational system and the social life on campus is totally different from what it was only a little more than a year ago. That the teaching to a large extent will be virtual, and that the interaction with your fellow students will be restricted.

But I would like to suggest that you may look upon this as a possibility. You see: Never before in the history of the University of Tokyo has a generation of students met challenges such as those that you are facing.

Please remember the following!

You know how Tamahagane is made? That is, the hard steel of the famous Katana swords? By hammering and repeated heating in the furnace the impurities are beaten away, and the iron is forged into a hard steel that can be given this unique strength and sharpness.

Another example: Do you know how palm trees grow in the tough climate of windy deserts? They may bend under pressure, but they will not break. When the wind blows hard, the roots of the palm tree will stretch and grow stronger than they were before. The palm tree grows because of these difficulties. Or as the old Latin proverb says: ”Sub Pondere Crescit Palma”.

You, too, students at the University of Tokyo, are like Tamahagane steel or palm trees. You may be facing a tougher situation than any student generation before you. But this will also enable you to develop a unique strength. You will be sharp like a Katana and stand high and firm like a palm tree.

Let me finish by again congratulating you, and wishing you all the very best for your future academic studies. I will close by repeating the haiku dedicated to you:

In gusts of spring rain

students sharpen their pencils

windows blow ajar

Thank you. Dōmo arigatō.

Svante Lindqvist

Former President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Founding Director of the Nobel Museum, Former Grand Chamberlain of the Swedish Royal Court

April 12, 2021

関連リンク

- カテゴリナビ